Fundamentalism is a religious movement within Protestant Christianity that has deep roots and strong influence in North Carolina. The movement emerged in response to nineteenth-century liberal theology and Darwinism, with an emphasis on preserving certain historic biblical doctrines as constituting the vital minimum of the Christian faith. Common fundamentalist doctrines are the inerrancy of the Bible, the virgin birth, the bodily resurrection of believers, and the second coming and thousand-year reign of Christ (millenarianism). Rooted primarily in the theology of Irish clergyman J. N. Darby, Britain's Charles Haddon Spurgeon, and American evangelist Dwight L. Moody, fundamentalism was eventually codified in 90 articles by 66 interdenominational essayists-one of them a Quaker woman. Published in a dozen booklets between 1910 and 1915, The Fundamentals encapsulated conservative biblical scholarship from America, Britain, Canada, Germany, Ireland, and Scotland. Fundamentalists are also referred to as simply "conservative" or "orthodox" Protestants.

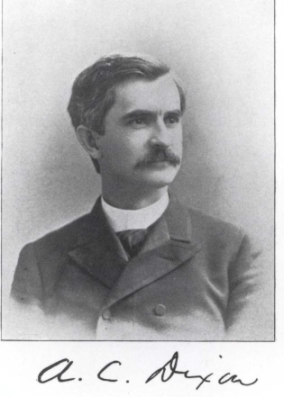

The Fundamentals was conceptualized and edited originally by North Carolinian Amzi Clarence Dixon, who promoted the ideology of Darby in his sermons and books and who eventually succeeded to the pulpits of both Spurgeon in London and Moody in Chicago. Before doing so, however, Dixon's North Carolina labors led to the conversions of Charles B. Aycock and Locke Craig, future North Carolina governors; Charles B. Alderman, later the president of North Carolina State University, Tulane, and the University of Virginia; Leonard G. Broughton, founder of the Georgia Baptist Hospital, which became the inspiration for Baptist Hospital in Winston-Salem; J. G. Pulliam, later to be President Warren G. Harding's personal chaplain; and George W. Truett (who converted under Pulliam), later the famed pastor of the First Baptist Church of Dallas, Tex., and a Southern Baptist icon. Upon his death during the Scopes Trial, Dixon was warmly eulogized by no less a source than H. L. Mencken's Baltimore Sun. Besides Dixon, other North Carolina-connected contributors and editors associated with The Fundamentals were Reuben Archer Torrey, William J. Erdman (a co-founder of the Moody Bible Institute in Chicago) and his son Charles R. Erdman, and Charles Bray Williams.

North Carolina was a fertile field for fundamentalists, beginning in the 1880s with the activities of the "Cotton Mill" revivalist, R. G. Pearson, in Salisbury and those of William J. Erdman in Asheville. Methodist revivalist Sam P. Jones, called the "Moody of the South," was liberally supported by tobacco magnate Gen. Julian Carr of Durham. Jones was almost certainly one of the Methodist revivalists whom James B. Duke credited with prompting his liberal endowment of Trinity College. He also preached in Charlotte, Winston-Salem, and Wilmington. Meanwhile, in Nashville, Tenn., Tom Ryman, a sobered-up riverboat captain, was building a permanent tabernacle-later home of the Grand Ole Opry-in which Jones could preach, using some of the proceeds of Jones's offerings earned in North Carolina. In 1893 Moody himself spoke in Charlotte and Wilmington.

A succession of fundamentalist revivalists roamed North Carolina thereafter until the climactic conversion in 1934 of one-time Presbyterian Billy Graham under the preaching of Southern Baptist Mordecai Ham. Included among them were Dixon, Torrey, W. P. Fife, J. Wilbur Chapman, George Needham (a founder of the Niagara Prophetic Conferences, which became a model for the Montreat Bible Conferences in Black Mountain), Bob Jones, Cyclone Mack, Billy Sunday (supported by James B. Duke and Josephus Daniels, and under whom R. J. Reynolds testified to a conversion experience), "Old Fighting" Bob Shuler, Monroe Parker, Fred Brown, Jimmie Johnson, Gipsy Smith, J. Frank Norris, W. B. Riley, T. T. Martin, John Roach Straton, Napoleon Bonaparte Honeycutt, and Vance Havner. Other contributors to The Fundamentals known to have spread its message throughout the state include C. I. Scofield and Arno C. Gaebelein. Though he did not directly contribute to The Fundamentals, A. T. Robertson of Statesville emerged from Wake Forest College as a world-class Greek scholar and a participant in fundamentalist Bible conferences nationwide.

In addition to traveling revivalists, some fundamentalists settled down in pastorates throughout North Carolina. These included the Baylor-trained Texan Robert E. Neighbour at the First Baptist Church in Salisbury. Neighbour, along with A. C. Dixon, became one of the founding fathers of the Baptist Bible Union, which would eventually ordain famed Christian radio evangelist Charles E. Fuller. In later years, Neighbour's grandson influenced Paige Patterson to attend New Orleans Baptist Seminary, where he teamed up with Texas judge Paul Pressler to spearhead the historic conservative resurgence in the Southern Baptist Convention in the last third of the twentieth century. Another North Carolinian who figured prominently in the fundamentalist movement was Jasper Cortenus Massee, pastor of Tabernacle Baptist Church in Raleigh.

Although Southern Baptists dominated the fundamentalist movement in North Carolina, Presbyterians such as Burlington's William P. McCorkle and Charlotte's Albert S. Johnson were particularly active in the state's evolution controversy, which preceded the Scopes Trial by only a few weeks and drew the ire of future Watergate prosecutor Sam Ervin Jr. Weston R. Gales, an Episcopalian from the prominent publishing family, was active along with A. C. Dixon and others in the establishment of Montreat and its associated Bible conferences. Some Southern Baptists, such as Charles Stevens in Winston-Salem, found many of their fellow Baptists irredeemably liberal and withdrew from the Southern Baptist Convention altogether, forming the independent Piedmont Bible College. Others, such as James Bulman (East Spencer), Gerald C. Primm (Greensboro), M. O. Owens (Gastonia), Robert Tenery (Morganton), and Calvin Capps (Greensboro) remained within the convention.

Many fundamentalist Christians, seeking to divorce themselves from the "worldliness" of American society, were reluctant to engage in political activity throughout much of the twentieth century. Beginning in about the 1970s, however, a loose association of conservative Christian groups-many avowing fundamentalist theologies-grew into a movement that came to be known as the "new religious right." The movement sought to combat or eliminate "big government," communism, secular humanism, abortion, homosexuality, pornography, illegal drug use, and other forces deemed detrimental to traditional moral and religious values. Prominent leaders of the new religious right included Jerry Falwell, Robert Grant, Beverly and Tim LaHaye, and Pat Robertson, working through organizations such as the Moral Majority, the Christian Voice, Concerned Women for America, the Religious Roundtable, and the American Coalition for Traditional Values. While the national influence of these fundamentalist-rooted groups may have peaked during the 1980s, conservative religious traditions maintain a significant influence in North Carolina worship, culture, and politics. By some estimates, 15 to 20 percent of North Carolinians consider themselves adherents of Christian fundamentalism, practicing their faith in a wide variety of Protestant, nondenominational, and "Bible" churches throughout the state.