See also: Black and Tan Constitution; Convention of 1835; Convention of 1868; Convention of 1875; Governor

North Carolinians have lived under three state constitutions-the Constitution of 1776, which created the government for the new state and was substantially amended in 1835; the Constitution of 1868, which brought the state back into the Union after the Civil War but was later amended to discriminate against African Americans in a variety of ways; and the Constitution of 1971, which reorganized the entire state government in light of the requirements of the modern economy and society. In general, each constitution expanded the rights and privileges of the citizenry as well as sections of the government. The countless struggles, successes, and failures experienced in the years between the American colonial period and the end of the twentieth century have been reflected in the development of North Carolina's constitution. Since 1971, important amendments have included setting the voting age at 18 and allowing the governor and lieutenant governor to be elected to two consecutive terms.

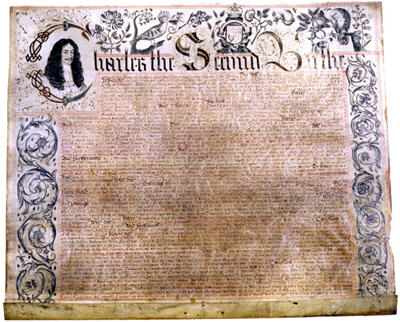

The Carolina Charter and the Constitution of 1776

Before North Carolina became a state, its people were subjects of the English Crown and lived in accordance with English law. The Carolina charter of 1663, which many colonists referred to as their "constitution," assigned governance of the colony to the Lords Proprietors and clarified the relationship between the residents and their home country. The charter guaranteed them specific liberties and protections-their "rights as Englishmen" established by the Magna Carta of 1215. When some of these guarantees were violated by conflicting instructions from London, the people protested, contributing to the growing movement for independence.

In December 1776 North Carolina's Fifth Provincial Congress, under the leadership of Speaker Richard Caswell, created a state constitution to reaffirm the rights of the people and establish a government compatible with the ongoing struggle for American independence. In drafting this document, North Carolina leaders sought advice and examples provided by John Adams of Massachusetts. They also consulted the newly adopted constitutions of Virginia, Pennsylvania, Delaware, and New Jersey and received specific instructions from the North Carolina counties of Halifax, Mecklenburg, and Rowan. The final version of the constitution was adopted by the legislature without further input from the people of the state.

The 1776 constitution explicitly affirmed the principle of the separation of powers and identified the familiar three branches of government (executive, legislative, and judicial). It gave the greatest power to the General Assembly, which would make the laws as well as appoint all state executives and judges. The governor, serving a one-year term, would exercise little power-the result of grave conflicts with previous royal governors. Even his modest opportunity for personal leadership was hedged in many instances by the requirement that he receive the concurrence of a seven-member Council of State, also chosen by the legislature, for any initiative he might want to exercise. Local officials established by this constitution also included the sheriff, coroner, constable, and justice of the peace.

In 1789, for the first time ever, the General Assembly amended the constitution to add Fayetteville to the list of borough towns permitted to elect a senator. (The constitution would not be revised for another 46 years.) Another change substituted the word "Christian" for "Protestant" to remove any doubt about the eligibility for office of a popular judge. The possibility of relocating the constitutionally designated state capital after a destructive fire was considered, but the idea was dropped and a new capitol was built in Raleigh.

Popular representation in the legislature was inadequately addressed by the Constitution of 1776. Local representation was based on units of local government. Voters of each county elected one senator and two members of the House of Commons regardless of area or population. Six constitutionally designated towns were permitted to elect an additional member of the House. The system gave preference to landowners and afforded little political voice to most of the population. As a result of these shortcomings, over time the constitution came under attack. The convention of 1835, with its substantial constitutional amendments, was an attempt to strengthen the 1776 constitution and improve the political system it created. The number of members of the House and Senate were fixed at 120 and 50, respectively (these figures remained the same in the early 2000s). More populous counties received more representatives. Among other important amendments adopted by the convention, the governor's position was strengthened by providing for his popular election for a two-year term.

The Constitution of 1868

After two state conventions (1861-62 and 1865-66) dealt with North Carolina's secession from the Union and subsequent reentry after the Civil War, a new national authority obliged the state to make its laws conform to terms dictated by the occupying Federal forces. At the time, many former leaders had been disfranchised, and a number of newcomers or otherwise inexperienced men, as well as appointed or otherwise installed civil officials, were in positions of authority. At the direction of the U.S. Congress, in which North Carolina was not then represented, delegates to a constitutional convention were duly elected in April 1868 to consider certain subjects mandated by the national government.

The Constitution of 1868, ratified by North Carolinians by a vote of 93,086 to 74,016, was a relatively progressive document that borrowed from the previous state constitutions and added new provisions. It abolished slavery and provided for universal male suffrage. The power of the people to elect representatives and other officeholders-including key officials in the executive branch, judges, and county officials-was greatly expanded. Voters' rights were increased, with male citizens no longer required to own property or meet specific religious qualifications in order to vote. The position of governor was again strengthened with increased powers and a four-year term. A constitutionally based court system was established, county and town governments and a public school system were outlined, and the legislature's methods of raising revenue by taxation were codified. Amendments in 1873 and 1875 weakened the progressive nature of the 1868 constitution. They also clarified the hierarchy of the court system and gave the General Assembly jurisdiction over the courts as well as county and town governments. In 1900 the universal suffrage established in 1868 was diminished by the requirement of a literacy test and poll tax-effectively disfranchising many blacks, Indians, and others.

The Constitution of 1971

After nearly 70 constitutional amendments between 1869 and 1968 and a growing desire for a new constitution in the 1950s and 1960s, the North Carolina State Constitution Study Commission, composed of lawyers and public leaders, was formed to evaluate the need for and outline substantial revisions. The General Assembly endorsed 6 of the 28 amendments proposed by the commission. At a general election on 3 Nov. 1970, citizens approved 5 of the 6 measures, rejecting repeal of the literacy test for voting.

The North Carolina Constitution of 1971 clarified the purpose and operations of state government. Ambiguities and sections seemingly in conflict with the U.S. Constitution were either dropped or rewritten. The document consolidated the governor's duties and powers, expanded the Council of State, and increased the office's budgetary authority. It required the General Assembly to reduce the more than 300 state administrative departments to 25 principal departments and authorized the governor to organize them subject to legislative approval. It provided that extra sessions of the legislature be convened by action of three-fifths of its members rather than by the governor alone. And it revised portions of the previous constitution dealing with state and local finance.

Other provisions permitted the levying of additional county taxes to support law enforcement, jails, elections, and other functions; enabled the General Assembly, rather than the state constitution or the courts, to decide what were necessary local services for taxing and borrowing purposes; abolished the poll tax, which for many years had not been a condition for voting; and authorized the General Assembly to permit local governments to create special taxing districts to provide more services and to fix personal exemptions for income taxes. In addition, the new constitution addressed the ongoing needs of public education, especially regarding funding, school attendance, and organization of the State Board of Education. The legislature's responsibility to support higher education, not just among the campuses of the consolidated University of North Carolina, was also affirmed.