The regulation of utilities in North Carolina has always reflected the tension between the goals of private business and the needs of the public. It has been shaped by massive technological change, changes in the respective roles of the federal government and the states, and changes in ideas about economic fairness, government's regulatory function, monopoly, and business competition.

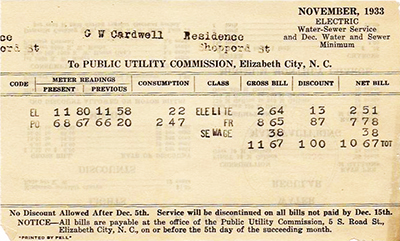

Since the late nineteenth century, North Carolina law has defined public utilities to include companies transporting freight or passengers by railroad, motor trucks, and buses; certain forms of communication service, especially by telephone and telegraph; and certain kinds of industrial and residential services, including electricity, natural gas, and water and sewer distribution, collection, and treatment. The most important aspect of state control has been the power to determine the rates utilities can charge for services. Political justification for extensive regulation stems from the belief that citizens are entitled to the benefits of public utility services at reasonable rates.

The development of modern public utilities regulation can be traced to the construction of a comprehensive railroad network after the Civil War. The increasing size and monopoly status of railroads drove rural shippers dependent on railroads and anxious for low rates to support more regulation. The shippers' efforts culminated in the creation of the Board of Railroad Commissioners, or the Railroad Commission (1891-99), by the Farmers' Alliance-dominated 1891 General Assembly. This measure placed the rates of telegraph, telephone, steamboat, and canal companies under the control of the Railroad Commission. Between 1920 and 1941 there was substantial public debate about the commission's future structure and role. Eventually, this produced a reconfiguration of utility regulation that recognized the special character of utility business.

After World War II, growing demands for utility services resulted in a more bureaucratic regulatory structure. In 1949 legislation increased the size of the Utilities Commission (created in 1941) and allowed it to reorganize its internal operations. At that point the commission's full-time staff was placed into separate divisions for accounting, electricity, telephone, motor passenger, and motor freight. Between the early 1960s and the late 1970s the regulation of utilities in North Carolina was characterized by utilities' numerous demands for rate increases.

By the late 1980s, the number of large electric and telephone rate increase cases, which had been a primary focus of utility regulation in North Carolina between 1974 and 1988, had dramatically declined. In addition, although rate regulation had initially been directed to the transportation sector, especially railroads, by the mid-1990s private passenger train service had been obsolete in the state for more than two decades. Even intrastate railroad freight rates and service issues had been deregulated or preempted by federal law. Federal deregulation and preemption also affected the intrastate motor freight and motor passenger industries, which had been an important object of regulation in North Carolina from the 1930s to the 1980s. Most dramatically, traditional rate regulation in the telephone and electric industries was challenged in the 1980s and 1990s by technological transformations and related antiregulatory policies at the federal level.

Despite the broad trend toward deregulation, utility regulation in North Carolina by the early 2000s remained a complex administrative task. In the 1990s, for example, the Utilities Commission had resolved a large number of utility matters. It conducted almost 1,000 proceedings in 1994 and regulated more than 2,000 companies, including those providing electric service, telecommunications service, water and sewer service, natural gas service, and various forms of transportation services, such as intrastate buses, railroads, and motor freight.