African Americans have served in the U.S. military since the days of George Washington, but it took until July 26, 1948, for the country to begin living up the democratic ideals that they fought to defend.

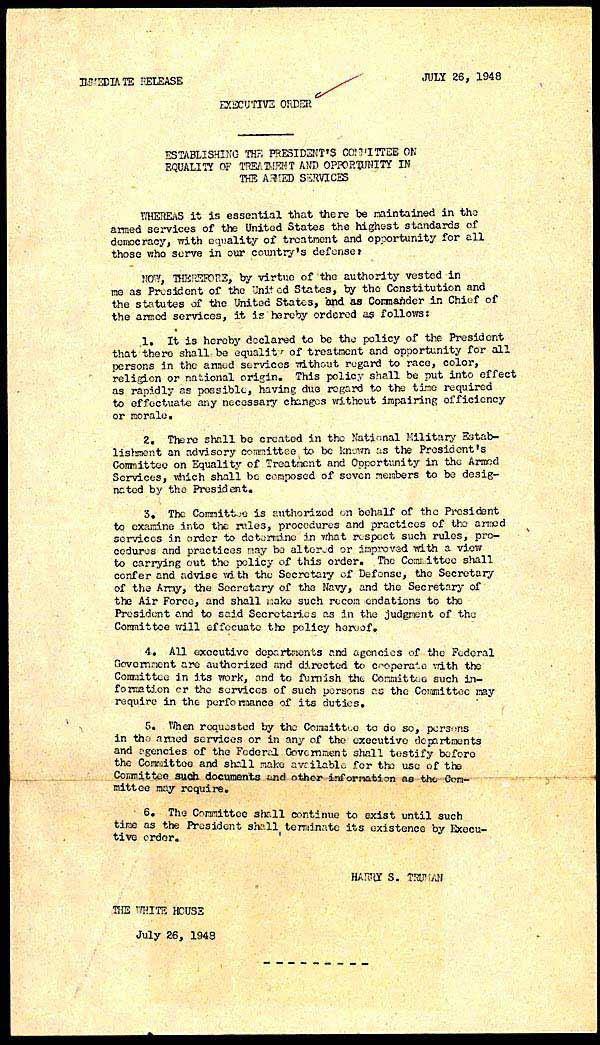

The year 2008 marked the 60th anniversary of President Harry S. Truman's Executive Order 9981, issued July 26, 1948, declaring that "there shall be equality of treatment and opportunity for all persons in the armed services without regard to race, color, religion or national origin."

As many as 5,000 African Americans, drawn largely from the population of free blacks living in the Northern states, but also from the slaveholding South, are estimated to have served beside whites in the Continental Army during the American Revolution. When America fought a devastating Civil War from 1861 to 1865, more than 100,000 African Americans served in the Union forces.

Although the Civil War ended slavery in the United States, the nation failed to address deep-rooted prejudices based on race and class in America, allowing bigotry and segregation to continue tarnishing the American dream.

Nevertheless, prominent 19th-century African American leaders, including civil rights pioneers Frederick Douglass and W.E.B. DuBois, encouraged black men to serve in the U.S. military, believing that by proving their loyalty and courage, they eventually could improve their position in American society in the face of discriminatory segregation laws and the ever-present threat of violence facing African Americans, particularly in the South.

"Let the black man get upon his person the brass letters, U.S.," wrote Douglass. "Let him get an eagle on his button, and a musket on his shoulder and bullets in his pocket, there is no power on earth that can deny that he has earned his right to citizenship."

From Buffalo Soldiers to Tuskegee Airmen

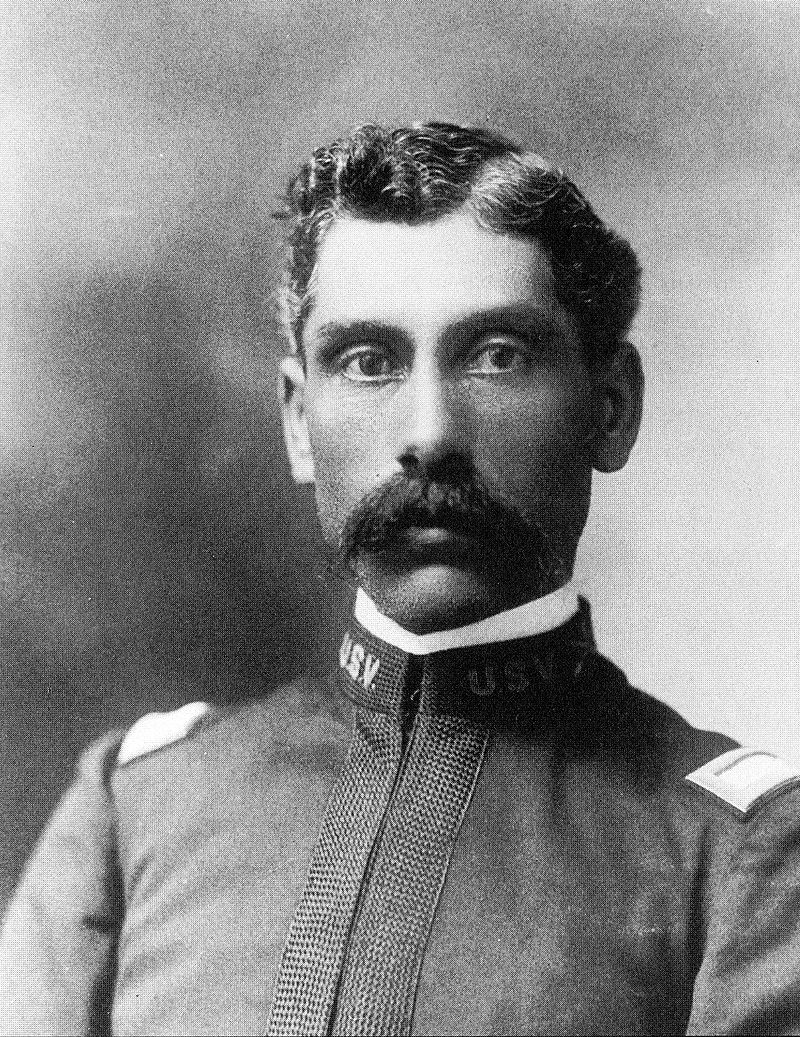

Although often confined in separate, white-led, noncombat labor units, African American soldiers volunteered time and again for combat and field medical duties. They served with distinction during the Civil War in the 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry regiment, immortalized in the 1989 film Glory; in the black cavalry units known as the "Buffalo Soldiers," who fought in the Indian wars and the Spanish-American War; and in the 369th Infantry, the "Hell Fighters from Harlem," who were awarded the French Croix de Guerre (Cross of War) for their heroism during World War I.

As World War II approached, the United States found itself opposed to fascist regimes and their racist ideologies, yet it had to reckon with the hard reality that many of its own 12.6 million African-American citizens -- about 10 percent of the population at the time -- were denied basic civil rights and human opportunities.

The bitter irony that President Franklin D. Roosevelt's "Four Freedoms" (freedom of speech, freedom of worship, freedom from want and freedom from fear) set forth as U.S. war aims were largely unavailable to African Americans did not stop 2.5 million black men from registering for the military draft. More than one million eventually served in all branches of the armed forces during World War II. In addition, thousands of African-American women volunteered as combat nurses.

At the same time, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), the Urban League and other organizations appealed to the White House and the military, winning the integration of officers' training and expanding opportunities for all-black units.

Among the best-known black units in World War II were the Tuskegee Airmen, a group of African American military pilots, who distinguished themselves in Allied campaigns in North African and the Mediterranean, becoming the only fighter escort group never to lose an Allied bomber to enemy action during the war.

African American truck drivers and mechanics were also the backbone of the "Red Ball Express," the massive effort to keep the Allies supplied as they moved across Europe to end the war.

"And when I say 'All Americans'"

Toward the end of the war, in 1944-45, the military began experimenting with integrated units to meet personnel shortages during the Battle of the Bulge on the German-Belgium border and elsewhere. As a result, more than 80 percent of the white officers reported that African American soldiers had performed "very well" in combat and 69 percent saw no reason why African American infantrymen should not perform as well as white infantrymen if both had the same training and experience.

But back home, racist attitudes persisted. When returning African American veterans became victims of violence in South Carolina and Georgia, President Truman took bold action, submitting a package of wide-ranging civil rights reforms to Congress and using his constitutional authority as commander in chief of the U.S. military to order desegregation of the armed forces.

"It is my deep conviction that we have reached a turning point in the long history of our efforts to guarantee a freedom and equality to all our citizens," he told members of the NAACP in a 1947 speech. "And when I say all Americans -- I mean all Americans."

By the end of the Korean War in 1953, the U.S. military was almost completely desegregated, including desegregation of buses and schools on military bases.

Sixty years later, it is evident that Truman's order transformed not only the armed forces, but broader American society as well, by serving as a powerful blow against segregation and further opening the way to the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 1960s.

William McBryar

William McBryar James Timonty Brynm

James Timonty Brynm President Harry Truman desegrates the armed forces

President Harry Truman desegrates the armed forces Desegregation of the Armed Forces

Desegregation of the Armed Forces