As settlers spread across the Piedmont, the colonial government struggled -- and often failed -- to keep up with them. Residents of the Piedmont grew to resent those failures. In the 1760s, groups of settlers calling themselves Regulators signed petitions, refused to pay taxes, and ultimately used violence in an effort to force the colonial government to treat them fairly. But the seeds of that conflict were sown much earlier in the colonial period.

The Granville District

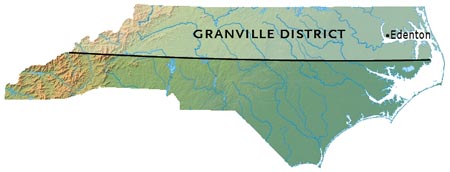

When North Carolina became a royal colony in 1729, one of the Lords Proprietors, John Carteret, Earl Granville, refused to sell his share back to the crown. He was given the northern portion of North Carolina, a 60-mile wide strip of land south of the Virginia border, as his property. Although he had no say in the colonial government, he continued to collect quitrents and taxes. The region under his control -- which included as much as two-thirds of the colony's population in 1729 -- was known as the Granville District.

Lord Granville sent agents to prepare rolls, or lists, of everyone living on his land and to collect quitrents and taxes. But these agents often failed to do their job, which meant that Granville didn't actually collect much money. Worse, it was difficult for settlers to obtain titles to their land -- legal documents stating that they owned the land they lived on. The District's land office in Edenton was not open on a regular schedule, and his agents kept poor records or overcharged settlers and pocketed the extra money. It wasn't clear which lands had been granted and which were still available. As a result, squatters occupied much of the District's territory, living on land and farming it without clear legal title to it.

The arrangement frustrated not only settlers trying to buy land but also the colonial government, which had only limited authority over the Granville District. When residents of the District refused to pay taxes because they were being treated unfairly, people in the southern part of the colony refused to pay for the entire cost of running the government. Representatives of the Albemarle and from the area around Wilmington fought in the colonial Assembly, tying up the government.

Although the problems of the Granville District affected most of the colony, they hurt worst in the Piedmont, where settlers needed the land office to grant them titles to newly occupied land. The difficulty of travel between the coast and the Piedmont also meant that the colonial government had even less control over officials and agents there than in the east, and Piedmont residents found it difficult or impossible to have their problems resolved. Not until the Revolution, when the new state of North Carolina took over the Granville District, would these problems be resolved.

New counties

Each county had its own government, just as counties do today, with a county seat where courts were held and where government offices were located. Settlers had to travel to the county seat for court days and to register wills or deeds, and in large counties, travel on horseback or on foot to the county seat might be quite a burden. Additionally, representation in the colonial Assembly was divided by county, and as population in western counties grew rapidly, westerners might not be fairly represented in the colonial government. Eastern representatives were mainly concerned with helping their part of the colony, and if they dominated the Assembly, the concerns of westerners wouldn't be addressed. And, of course, easterners were perfectly happy with the way things were -- they didn't necessarily want to share power with the west.

For these reasons, it was important for the Assembly to establish new counties promptly when old counties grew too large. By the 1750s and 1760s, though, the population was growing faster than the Assembly could, or would, create new counties. This, too, led to resentment in the Piedmont.

After the Regulator conflict from 1768-1771, new western counties were created. During the Revolution, the new state legislature grew more responsive to the needs of westerners -- in part to keep their support in the war against the British.