Laura Cox began working for Washington Duke in his first tobacco factory when she was eight years old. In 1926, her story of 42 years of service -- without so much as a single vacation -- to the Duke family's tobacco ventures was featured in a local newspaper. An excerpt of the article is below, with a focus on her words from an interview. In the interview she discusses her experience as an employee and the tasks of tobacco processing in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, including rolling thousands of cigarettes by hand each day.

Miss Laura Cox has 39 days absence from work against her record during 42 successive years of employment in the tobacco business; she began working in the one-room cabin which constituted Washington Duke's first factory; with the growth of the company she moved into the other buildings and today she works at Ligett&Myers Tobacco Company; strict aplication to duty during work hours and complete relaxation is her prescription for continued good health.

" ... I have been working for the Duke concern for about 42 years with never a vacation. I went there from home at the age of eight years, and have been there ever since. I was employed by Washington Duke, upon the recommendation of my sister, who was at the time working in the one-room factory. At the time of my employment, there were about 200 people employed at the factory and the majority of these were women.

"The factory occupied a small plot of ground just this side of the present West Main street and just a little west of the present Liggett and Myers tobacco factory.

"A two-story wooden building located not far from the factory was used for the storing and "beating out" the raw product. The "beating out" process consisted of taking the tobacco as it came direct from the farms and beating it into pieces small enough to be rolled into cigarettes. The parts that were too coarse to be used in cigarettes were used in making smoking tobacco for pipes and were put up in bags. From this storage house the tobacco was carried in boxes on the shoulders of a few men to the little one-room factory. Here it was placed on a table and the people employed in the factory had to get their tobacco from the table to roll into cigarettes.

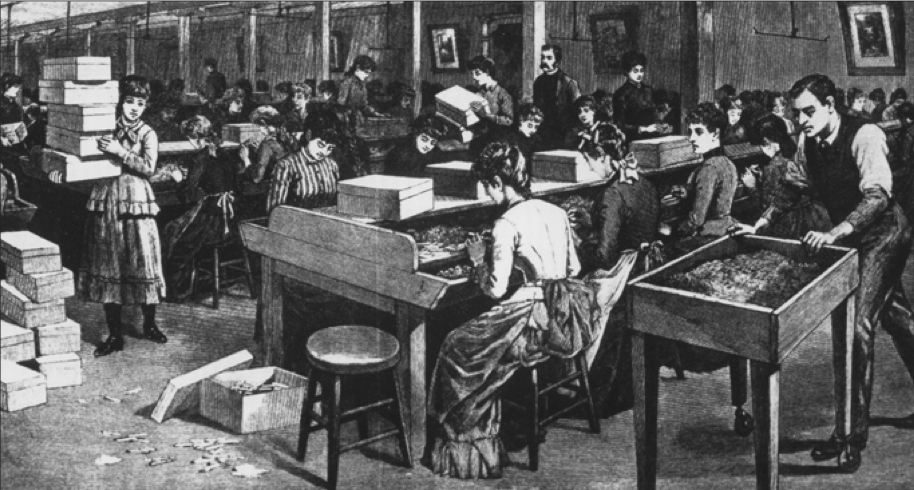

"The equipment of the factory consisted of a few tables divided into partitions of about four feet each. At each of these tables were employed six girls who rolled the cigarettes by hand. At that time the majority of the employees were Jews from the North.

"The brands made at this time and also for a good while after the factory made its first expansion were "Duke of Durham," Crosscut, and "Pinhead." There was also the "Velvet Mouthpiece" brand which was considered to be a product very much superior to the other brands. For making the three inferior brands an employee was paid at the rate of 55 cents per thousand, and for the superior "Velvet Mouthpiece" brand 65 cents per thousand was paid…

"Then one started the day's work off by getting a supply of tobacco on her table. A good day's work was considered to be the production of about 2,000 cigarettes, and it took about two pounds and three ounces of tobacco for every thousand cigarettes, so you see one person could not work out but about an average of four pounds a day.

"After getting the tobacco on the table the employee took a portion of it and put it under a damp cloth. This was done in order that the tobacco would return its freshness until it was used up. After getting the tobacco all under the cloth it was pressed flat so as to get it in better form to work with.

"When all was ready, the employees would take a portion of the tobacco from under the cloth and place it on the table directly in front of her. This small portion of tobacco was, for some unknown reason, called a "monkey" was in amount about enough for one cigarette. Directly in front of the employee was a small pasteboard square called the "kleunky" on which the actual rolling was done. Taking the tobacco up in one hand, it was placed on the paper very carefully particularly attention being given to its smoothness and the clean appearance of the paper it was being wrapped in. After the cigarette had been rolled it was stuck together with paste which every operator had in easy reach. It was here that the skill was required for too much paste on a cigarette would make it have a black appearance and thereby prevent its being marketed.

"When the employee had made a good number of cigarettes, she would stack nine of them between her fingers and trim the ends with a pair of shears. This operation also required great skill for it was very easy to ruin several cigarettes with one miscut with the shears.

"While employed here, we were at liberty to quit work any time during the day and to stay out for any length of time. Often some of the employees would go home during the day and not return until the next day, or perhaps for several days. Of course, deduction was made for the time lost, but when the employee returned, she went to work, back at her table, and with a new supply of tobacco. One could then go anywhere at anytime and stay as long as they desired, but there sure is a change in conditions now.

Source Citation:

"Long Record for Steady Work Held by Woman Who began Her Duties in Duke's First Factory." Durham Morning Herald. January 17, 1926.