See also: Bank of America; Bank of Cape Fear; Branch Banking and Trust Company; Central Carolina Bank & Trust Company; State Bank of North Carolina; Wachovia Corporation.

Banking, although important to North Carolina's economic health and stability for two centuries, became a major industry in the state only during the latter half of the twentieth century. The emergence of interstate banking, spurred by the 1985 U.S. Supreme Court decision upholding it, helped drive this growth. Led by mammoth corporations such as Bank of America, First Union, and Wachovia, North Carolina's banking industry has been characterized by mergers and acquisitions as well as increased competition through the establishment of new state-chartered banks.

North Carolina chartered its first banks in 1804, making it the last of the original 13 states to do so. That year the General Assembly chartered the Bank of Cape Fear as the state's first bank, followed later in the year by the Bank of New Bern. Limited wealth provided little opportunity for the accumulation of substantial capital. To provide services for small businesses, provisions were made for branch banks in other towns. This early practice made North Carolina a "bank branching" state, a concept that has persisted.

There were opposing views within the General Assembly on the proposed structure of a banking industry. One faction, consisting largely of Federalists, favored the establishment of private local banks such as the Bank of New Bern over a state bank, which it saw as a product of "the monied aristocracy." An opposing argument, made largely by Republicans, was for the establishment of a central state bank with branches throughout the state, owned and controlled jointly by the state and by individuals.

In 1810 the legislature chartered the State Bank of North Carolina. The bank's capital was set at $1.6 million, and the state treasurer was authorized to subscribe $250,000 in bank stock. The act required the state treasurer to use the full amount of the dividends from the state's stock to redeem paper currency issued earlier by the state. The headquarters of the State Bank of North Carolina was in Raleigh, with branches in several cities.

The State Bank of North Carolina quickly moved to cripple the operations of the Bank of New Bern and the Bank of Cape Fear by securing and presenting their notes for redemption. Instead of joining the State Bank, however, the Bank of New Bern was permitted in 1814 to establish branches in Raleigh, Halifax, and Milton, and the legislature granted the bank's request for recharter to 1835.

Public concern prompted the General Assembly to investigate the practices of state-chartered banks during the 1820s. A major examination of banking practices in 1828-29 was highly critical of state banks, and in the case of the Bank of New Bern, it exposed some irregularities and possible violations of its charter. By 1832, after some anxious years and with the help of generous creditors, the bank had paid off its obligations, but it was liquidated upon the expiration of its charter in 1835.

In 1791 U.S. Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton had persuaded Congress to charter the first Bank of the United States, essentially a private bank operating under a federal charter. Headquartered in Philadelphia, the bank had eight branches in major cities but none in North Carolina. The bank closed when it failed to have its charter renewed in 1811. Financial problems associated with the War of 1812, however, led to renewed plans for a central bank, and the federal government authorized the Second Bank of the United States on 10 Apr. 1816. Its capital was set at $35 million; stock subscriptions were sold in Raleigh, and a branch opened in Fayetteville in January 1817.

This was a major turning point in North Carolina's financial history, as the structural problems of the federal bank would significantly affect the state's banking industry. When President Andrew Jackson vetoed the bank charter renewal bill in 1832, the Fayetteville branch of the Second Bank of the United States closed. Following its demise, the regulation of bank credit and the nation's currency was left to state banks until the Civil War. In 1835 the Bank of the State of North Carolina was chartered as a successor to the State Bank of North Carolina. A new charter was granted in 1859 and the name was changed to the Bank of North Carolina, which finally closed its doors in 1866.

When North Carolina seceded from the Union on 20 May 1861, the state needed to raise funds immediately to support the military. Finance was a critical matter, and banks were induced to increase loans to the state. One step was to authorize the treasurer to borrow $1 million from the banks at 6 percent interest; the loan amount increased almost immediately to $3 million. That figure was increased to $8.4 million, one-third of the state's bank capital in 1862, as the war progressed. Financing the war was a major challenge to both the Confederate and state governments. In 1865 there was over $4 million in unpaid interest on state bonds. Surrender in 1865 did not stop the cost of the war. The banks had survived, but their doom was sealed when the U.S. Congress levied a 10 percent tax on all notes issued by state banks. Every bank in the state ceased operation, including the state's first bank, the Bank of Cape Fear.

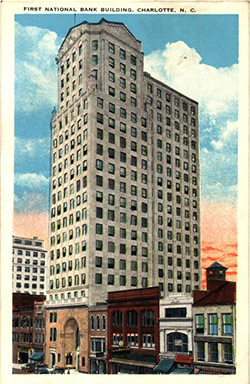

National banking came to North Carolina when the First National Bank of Charlotte was chartered on 1 Aug. 1865, followed on 12 September by the Raleigh National Bank of North Carolina. In 1866 three additional national charters were granted for banks in New Bern, Wilmington, and Salem. There were no banks chartered by the state until the Bank of Greensboro on 7 Apr. 1869. The state continued to struggle with the economic effects of the Civil War. In the 30 banks in operation in the state in 1875, total deposits were only $250,000.

Banks remained private businesses unsupervised by the state until 1887, when a law was passed to make banks report to the state treasurer twice annually. The North Carolina Corporation Commission was created in 1899, and authority over banks was given to the new body with provisions for regulation and examination. In 1921 the commission established a banking department.

During banking's "glory days" of the 1920s, almost every town in the state desired a bank. After the Great Depression began in 1929 with the crash of the stock market, smaller banks began to fail. Governor O. Max Gardner, backed by the North Carolina Bankers Association, won the battle for regulation, and Gurney P. Hood became the state's first commissioner of banks in May 1931. North Carolina was the last state to close its banks for the national bank holiday announced by President Franklin D. Roosevelt on 5 Mar. 1933. Within a few days most of the banks in North Carolina were reopened; the remainder were liquidated under the provisions of the order. From 1921 to 1933, 316 banks failed in the state.

Building on Charlotte's history as a financial center, several North Carolina banking institutions emerged as national and international leaders during the second half of the twentieth century. By the early 2000s, Charlotte had become the nation's second-largest financial hub, ranked behind only New York City. In an era that saw job losses and diminished economic health in industries such as manufacturing and farming, North Carolina banking has continued to play a vital role in the state's economy. By 2004 there were nearly 100 state-chartered banks and many other bank and trust companies in North Carolina licensed to offer financial services in the state.