The Federalist Party, originating in the early 1790s, endured longer in North Carolina than in any other southern state, although it generally achieved only modest success throughout its existence. The party never gained substantial long-term support in large measure because of its obvious disdain for democracy and popular sentiment, its reliance on the well-educated and propertied elite, and its failure to organize effectively. Moreover, the party supported a strong central government while most North Carolinians favored state rights. Only rarely were the Federalists able to balance the state's particular economic interests and political views with their party's ideology and policy agenda.

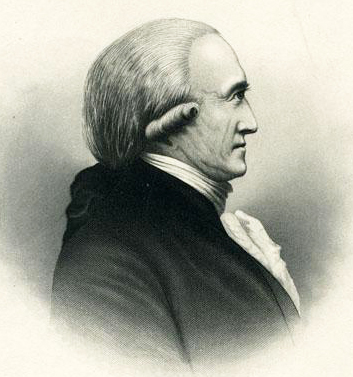

In the 1790s North Carolina Federalists experienced repeated disappointments at the polls. Only Richard Dobbs Spaight (1792-95), who later deserted the party, and William R. Davie (1798-99) became governors. Jeffersonian Republicans dominated the General Assembly, especially after 1792. The state sent just two Federalists to the U.S. Senate-Samuel Johnston (1789-93), an attorney from Chowan County, and Benjamin Hawkins (1789-95), born in Granville (now Warren) County and previously a North Carolina delegate to the Continental Congress and a U.S. Indian agent. The state's delegation to the U.S. House of Representatives contained a Federalist majority until 1793, but between 1793 and 1799 the only Federalist congressman from the state was William Barry Grove, a prominent Fayetteville attorney. At times the party provided North Carolina with able leaders in the judiciary, where most attorneys were Federalists. In the field of education, Federalists promoted the establishment of the state university-Davie being known as its "father"-and fought to maintain it.

During the presidential administrations of Thomas Jefferson and James Madison (1801-17), Federalist strength steadily eroded. Key party leaders had disappeared from the scene through retirement or death. Four Federalist congressmen-Archibald Henderson, William Grove, John Stanly, and William H. Hill-ignored instructions by the state's Republican legislature to vote for repeal of the Judiciary Act of 1801, and none was reelected. Federalist membership in the General Assembly hovered between 25 and 30 percent, reaching a peak of 40 percent in the Lower House during the War of 1812. Among the distinguished Federalists who served in this body were Archibald Henderson (1807-9, 1814) and William Gaston of New Bern (1807-9). Although the party experienced a brief revival with its opposition to the War of 1812, Federalist William Polk failed in his bid for the governorship in 1814.

The Treaty of Ghent and return of peace struck a mortal blow to Federalists in North Carolina, for they could no longer use the war as a political issue. Moreover, the Hartford Convention of 1814 reflected badly on the party nationwide as well as in North Carolina. The postwar upsurge of nationalism, embraced by Republicans, lured some Federalists away from the party. The election of James Monroe as president, the onset of the so-called Era of Good Feelings, and the lack of major national issues further blurred party lines. Few Federalists saw any reason to keep the party label and themselves stressed the disappearance of partisan differences. Although some old-line Federalists such as Gaston and Henderson kept the faith, by 1817 the party ceased to exist.