1805–28 Mar. 1883

James Thomas Leach, attorney, physician, and Confederate congressman, was born in the present-day Cleveland township of Johnston County. His grandfather, Dr. Thomas Leach, had lived in Bertie and Dobbs counties before the Revolution. After serving as a surgeon in that conflict, Thomas settled in Johnston County. In 1803 his son, John Thomas Leach, married Susannah Carter Parham of Mecklenburg County, Va. They established Leachburg Plantation near the Wake County line and built a large log home with the labor of the people they enslaved. It was here that their son, James Thomas, was born, according to family tradition, "in a snowstorm."

Family tradition also maintains that Leach studied law in Europe and at Rutgers College, but no record of any such attendance has been found. Soon, however, his admiration for his grandfather persuaded him to study medicine and he entered the Jefferson Medical School in Philadelphia. In 1833 he married Elizabeth Willis Boddie Sanders, whose family had resided near Smithfield since before the Revolution. The young couple built a home on Leachburg Plantation, where for the remainder of his life Leach practiced both law and medicine. He also gradually bought all the remaining shares of Leachburg inherited by his brothers and sisters. According to the census of 1860, he was listed as the enslaver of forty-seven people and owned an estate valued at $53,200.

Leach was a community leader in other ways. Out of charity, he took into his sixteen-room home several orphaned boys and two young ladies. For a while he maintained a school in his home, but later he built schoolhouses in the community for his and the neighborhood children. He also spent much time instructing his neighbors in better farming methods, urging them in particular to aim towards self-sufficiency.

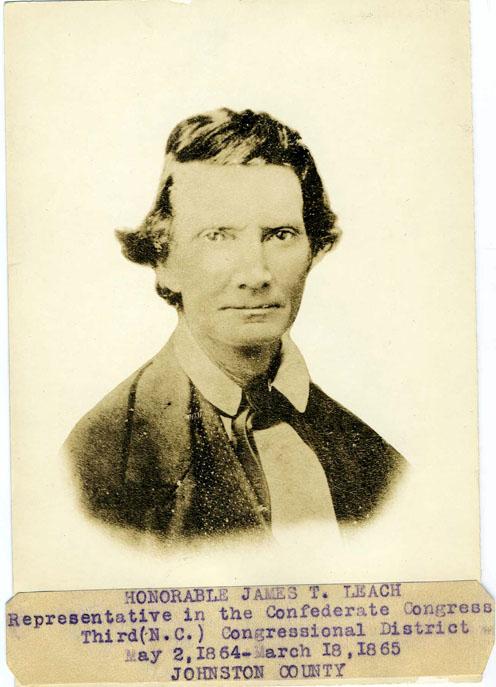

An old-line Whig, Leach in 1858 was elected to one term in the state senate, where he served on the committee on claims and on the joint committee on finance. He was a candidate for the House of Commons in 1862 but this time was defeated. During the secession crisis, Leach was a confirmed Unionist and opposed secession even after Abraham Lincoln's call for volunteers in April 1861. In 1863 he campaigned fiercely against three Confederate enthusiasts for a place in the Confederate House of Representatives. He pledged to seek "a just, honorable and lasting peace" and won handily.

In the Confederate Congress, Leach served on the committees on post offices and post roads and on territories and public lands. On the floor his unbridled antagonism to "reckless legislation . . . endorsed by the President and the mighty strides toward a military despotism" (Raleigh Weekly Standard, 13 Jan. 1864) placed him among the extreme malcontents. He voted to override every veto, to impugn the competence of every cabinet member so charged, and to oppose every major administration war measure. When President Jefferson Davis refused to open peace negotiations, Leach urged separate state action on the best terms available.

Leach apparently avoided the loss of any property after the war, for Branson's Business Directory for 1872 lists him as owning 2,900 acres of land. He was now an active prohibitionist and in 1875 resigned his place on the board of county commissioners rather than certify anyone as a "qualified" barroom operator. He also served as a director of the state psychiatric hospital for a number of years.

Leach was a man of strong opinions and a fiery and sarcastic speaker. When Richmond newspaper editors criticized his opposition to the Davis administration, he publicly declared that he wanted the editors "Dead, dead, dead!" (Richmond Daily Examiner, 23 Nov. 1864). He was a long-standing Mason and Methodist. Leach and his wife had eight children: John Sanders, James Thomas, Jr., Elizabeth Mary, Nancy Temperance, Claudius Brock, Sarah Louenza, Cornelia Susan, and Delia Ida. He died at home and was buried in the family cemetery near Mount Zion Church.