December 10, 1885-September 6, 1937

John Dudley Wray was an educator, agriculturalist, and North Carolina's first African-American Farm Makers’ Club (now 4-H club) Agent. He was born in Roxboro, North Carolina on December 10, 1885 and raised on a farm by his parents Sidney and Sarah Wray. Wray attended the Agricultural and Mechanical College for the Colored Race in Greensboro (now North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University) where he earned a Bachelor of Agriculture in 1909. Not long after receiving his undergraduate degree in 1910 he was hired to work at the Experiment Station at Tuskegee Normal and Industrial Institute. He was also employed with the Industrial Institute in Alabama (now Tuskegee University) under the supervision of Principal of Instruction Booker T. Washington and Agriculture Director George Washington Carver. Wray's title was First Assistant to the Farm Superintendent in the areas of nature study and gardening for rural schools.

In 1912 he returned to work at his alma mater, A&M College, as the Superintendent of the school’s farm and as a teacher of agronomy and agricultural engineering. Under his leadership, Wray used students instead of hired workers to perform labor and update the college farm. They constructed new modern buildings and drained swamp land to cultivate and grow larger and better crops. Included in the crops cultivated and harvested on the 108 acres of farm land were corn, alfalfa, clover and wheat. Under the expertise of Wray, the crops output tripled in one year. For his contributions to the college, Wray was awarded an Honorary Master's Degree in Agriculture in 1913.

Professor Wray was also known for his showcased work in rearing of animals, in particular, registered Berkshire and Duroc Jersey pigs. The pigs were housed on the farm and given the best care, resulting in large profits for the farm.

In February of 1914, Wray accepted a new position as Director of the Agricultural department at Lincoln Institute for Negroes in Simpsonville, Kentucky. After working in the position for over a year, Wray returned to his home state of North Carolina in 1915 and was appointed by B.W. Kilgore, Director of Agriculture Extension Service to serve as the Farmer Makers’ Club Agent for Negro boys between the ages of 10-18, teaching them to grow corn. He performed his Extension Service work in conjunction with A& M College. His official office was headquartered at the college where he also served as a faculty member. During this time his Extension service work consisted of traveling to rural areas to educate African American youth on best practices to grow foods and animals.

After 1916 other youth clubs were added, including crop rotation, potato, wheat, grain, cotton, peanut, pig and poultry clubs. The clubs eventually added young girls, parents and other adults interested in club work. Under Wray’s leadership agriculture clubs increased, with Wray organizing 189 out of the 335 clubs in the state. In three years membership numbers totaled 2,700, and in addition there were over 5,500 members that received instructions in the mail and did not take part in face to face supervision.

Wray was recognized for his work in the field of agriculture by his alma mater. An award called the John D. Wray (gold) medal was given to a student at the college with the best record of completion of four years in practical agriculture according to the 1917-1918 A&T college bulletin.

Wray was also active in the community where he served as a leader in local, state and national organizations. In 1908 he was the president of the YMCA in Greensboro for Negroes, and during the 1920s he served as the president of the A&T College Alumni Association and secretary and treasurer of the North Carolina Negro Farmers’ Congress. In addition, Wray as a community leader worked towards justice for drafted African American soldiers in the state of North Carolina who experienced race discrimination when serving in the military during the Great War.

In 1918 during World War I, Wray wrote a letter on behalf of “colored draftees” to Emmett J. Scott, Special Assistant to Secretary of War reporting specific clear-cut cases of purported inequalities. The discrimination complaints, along with others, led to federal investigations, eventually improving the military status of the soldiers. In a letter written by Emmett J. Scott to Colonel Roscoe S. Conkling, Office of the Provost Marshal-General on September 3, 2018, he referred to John D. Wray as a “substantial Negro farmer engaged in Cooperative Extension Work, headquartered at A&T College.”

Moreover, as a state agriculture agent during World War I, Wray organized the Uncle Sam’s Saturday Service league for African American youth in the state of North Carolina. The club was formed during a time of national emergency, as fewer workers were available to help grow crops and feed those in the United States as others fought the war overseas. The need for food was so great, nearly 5,000 African American youth ten years and older committed to working every Saturday afternoon to help in the effort to grow food until the war ended.

After serving ten years as the first African-American State youth agent in December of 1925, Wray resigned and accepted a position as a Professor of Agronomy, Rural Education and Entomology at what is now Florida A& M University in Tallahassee, Florida. The university honored Wray by offering the “John D. Wray Medal for Excellence in Agriculture” for the 1927-1928 school year.

Wray returned to North Carolina and later became an agriculture teacher at Laurinburg Normal and Industrial Institute during the 1930’s.

In 2009 the General Assembly of the State of North Carolina wrote a Joint Resolution to honor the one hundredth anniversary of the beginning of the 4-H program, including John D. Wray as one of the outstanding 4-H pioneers in the state.

Additionally, on June 7, 2012, Wray was honored on the U.S. Congressional floor by Senator Michael Bennet of Colorado for his support to the country through agriculture science and his efforts during World War I in growing food and supporting the military rights of African American soldiers. The “Remembering John D. Wray” comments are recorded in in the Congressional Record Proceedings and Debates of the 112th Congress, Second Session. John D. Wray’s granddaughter, Kathryn Green, now 75 years old of Denver, Colorado was instrumental in Senator Bennet honoring her grandfather. Wray’s daughter Thelma is her mother.

F.D. Bluford Library at North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University houses Wray’s personal collection. Much of the collection was digitized as part of the “Better Living in North Carolina” grant and is available for research.

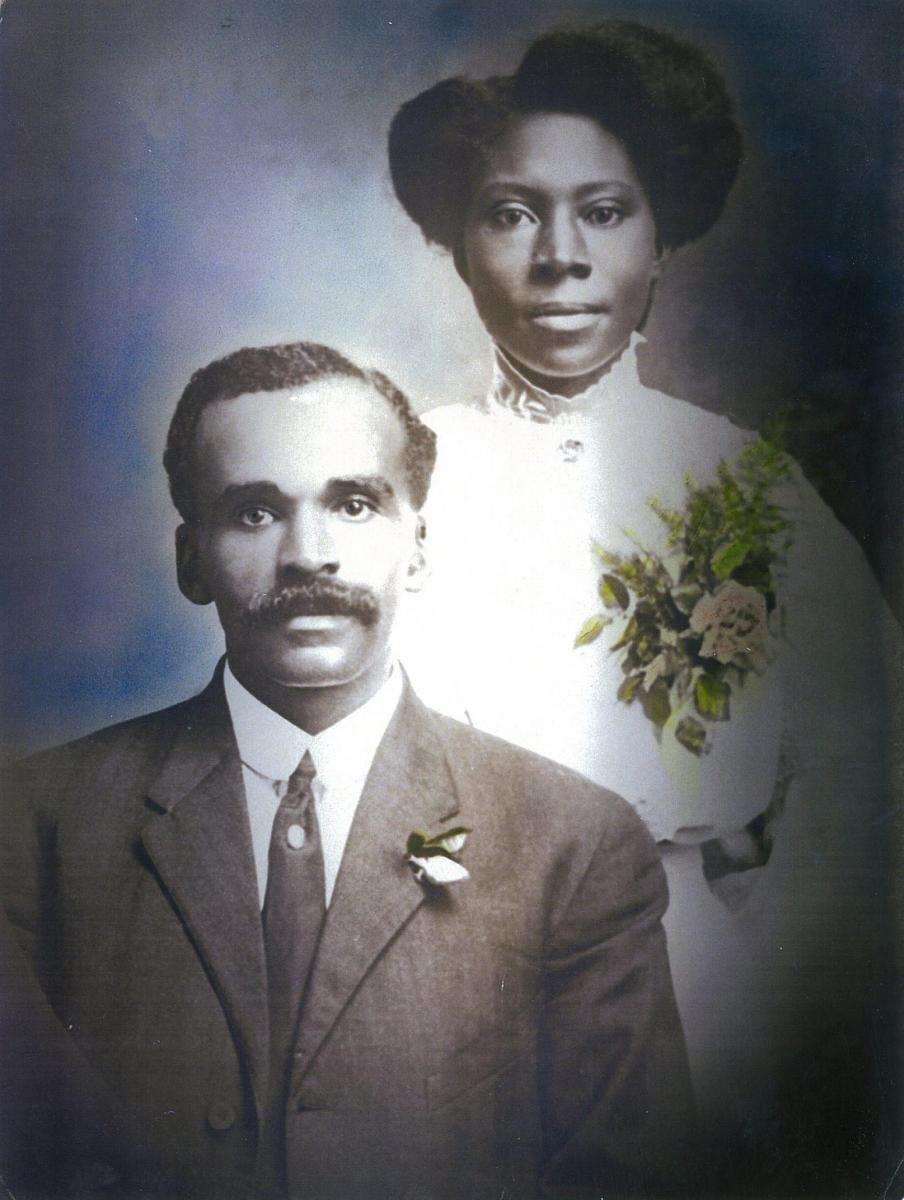

Wray was married to Annie Bell Harris in 1909 and had three sons, Richard, Emmitt, John Wray Jr. and one daughter named Thelma.

John D. Wray died on September 6, 1937 in Guilford County, North Carolina, and was buried in Maplewood Cemetery in Greensboro.

Online digital collections for John D. Wray:

“Digitized Collections of John D. Wray and S. B. Simmons” Better Living in North Carolina, https://www.lib.ncsu.edu/news/special-collections/from-the-collections-of-john-d-wray-and-s-b-simmons

"John D. Wray and the Fight for Black Farmers." NC Eats. Accessed August 05, 2019. https://nceats.omeka.chass.ncsu.edu/exhibits/show/raceandgender/racial_s....