See also: Community Colleges; Extension Service; Vocational Education

The history, purposes, and philosophy of adult education in North Carolina generally parallel those of adult education elsewhere in the United States, while manifesting some significant regional differences. Continuing education, literacy, adult basic education, higher education, professional for-profit business training, and workplace training are all important forms of adult education in the state. Prior to the Industrial Revolution, such adult education as there was occurred mostly at home or in church. White male landowners in North Carolina were much more likely than women, the indigenous population, or enslaved people to read, write, and compute. In 1816 the American Bible Society began a nationwide literacy campaign to place a Bible in every home: the Bible was frequently the only printed material in a household, and early literacy efforts were designed to equip at least one household member with the skills to read the text.

Native Americans in North Carolina, such as the Lumbees and Cherokees, relied largely on the oral tradition as a lifelong learning process. Storytelling, active modeling, and learning by doing fostered the education of youth, who in their adulthood would become teachers of the next generation. Enslaved people, for whom literacy was at times outlawed, drew on their African heritage of oral instruction: storytelling, song, and call-and-response (especially among field workers) were richly employed as means of instruction, community building, and survival in a new land. These traditions continue to serve North Carolinians of all races.

The Civil War, which drew thousands of the state's men into service, drained local resources and damaged both physical and social infrastructures. The church and the military were critical agents of adult education throughout the war years. Interestingly, the U.S. Congress used the context of the war to enact the Morrill Land Grant Act in 1862. Under this legislation, acreage was deeded to each state for the purpose of establishing an institution of higher education that would be equal to any in the private sector. This was the first time that federal resources were allocated to higher education. Southern states, including North Carolina, were deeded their land after the war, and the North Carolina College of Agriculture and Mechanic Arts, precursor to modern-day North Carolina State University, was founded in 1887. In the South, land grant universities mirrored the larger society in that they were segregated by race. In response to this situation, Congress passed the Second Morrill Act in 1890, conferring federal funds for agricultural and technical colleges for blacks. North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University in Greensboro had its beginnings in this second piece of legislation.

At the start of the twentieth century, adult literacy needs were addressed in various ways throughout the state. In many mill villages, basic educational opportunities were made available to workers and their families, often through village libraries. It was believed that illiteracy was worse in rural areas, where population was sparse and there was little communication. Many night schools, also called "moonlight" schools, were established, including those operated under the Community Schools Adult Education Program of Buncombe County, started in 1919 and used as a model in North Carolina as well as nationally. The main purpose of the community schools was to teach adults who could not read or write. Education was achieved through study of normal adult interests, such as reading the newspaper and the Bible, and through writing letters. The program was committed to helping adults who had "missed their chance" at education during childhood. Basic homemaking and nutrition principles and the ideal of community participation were also taught, and basic physical and medical needs were addressed. It was not uncommon for adults to walk several miles to get to a community school, and many pupils never missed a lesson. One 65-year-old woman walked two and a half miles each way to get to class, according to the records of her night school.

Since its inception in 1909, the North Carolina Agricultural (Cooperative) Extension Service has been the mechanism by which the educational needs of many of the state's people have been identified and addressed by the state universities-particularly the land grant universities, which are integrally tied to cooperative extension. Empowered by the federal government under the Smith-Lever Act of 1914, the Cooperative Extension Service provides services and offers programs through a network of higher education departments and faculty, experiment stations, and extension agents located throughout North Carolina. The system is a successful model of federal, state, and local cooperation that is often overlooked in basic education. Agriculture, small and medium business enterprise, homemaking, child care, and nutrition are among the areas in which cooperative extension plays a vital role in adult education.

In 1963 the Department of Extension Personnel was created under the College of Agricultural and Life Sciences at North Carolina State University. Renamed the Department of Adult Education in 1965 and the Department of Adult and Community College Education in 1970, this department offers short courses as well as master's and doctoral degrees in the field of adult education.

North Carolina's community college system originated in the 1950s and was strengthened considerably during the 1960s and 1970s. It is a 58-member system that complements the Cooperative Extension Service by offering both vocational and liberal arts programs. Located so that a community college is within reasonable driving distance of every North Carolinian, the institutions offer a variety of programs designed to address the needs of local communities as well as a standardized liberal arts curriculum similar to that of the state's public four-year institutions. Two-year degree programs, noncredit courses, adult basic education, vocational education, and industry-supported job training complement the liberal arts curriculum of community colleges in the state.

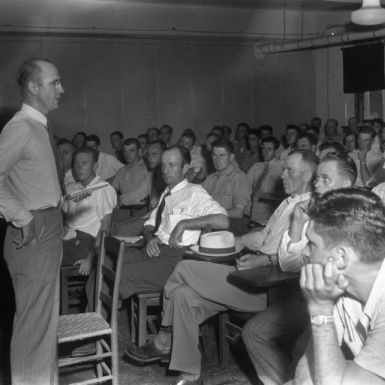

The U.S. military plays a key, if often overlooked, role in adult education in North Carolina. Its six installations, particularly the army's Fort Bragg, are complexes wherein continual training and education are essential. Federal funding and commitment, while varying throughout the twentieth century, ensured the continuance of the military presence in North Carolina and the ongoing education of all service members.

In the last decades of the twentieth century, the state's economy, led by the high-tech and pharmaceutical industries, diversified tremendously. On-site training became a common means of adult education. With the tremendous growth of the Research Triangle Park, which has attracted multinational corporations and big businesses since its creation in the late 1950s, companies such as IBM, Nortel, and SAS have come to be leaders in human resource development and training.

Governors and other government officials, chambers of commerce, the YMCA and YWCA, and agencies such as teacher organizations and parent-teacher associations, as well as private individuals, have addressed adult literacy in North Carolina in a number of ways. In 1987 Governor James G. Martin created the Governor's Commission on Literacy, chaired by William C. Friday, former president of the University of North Carolina System. The commission's report noted programs and institutions already in place to address literacy and basic-skills needs, such as community colleges, county literacy councils, community action groups, private industry councils, and public libraries.

In the 1980s and 1990s North Carolina saw a large influx of residents attracted to the state by its beauty, its strong job market, and its relatively low cost of living. Newcomers tended to be workers from other regions of the country in search of enhanced employment opportunities or retirees seeking a new lifestyle in the Sun Belt. Many had advanced degrees and arrived with expectations for further educational opportunities and enrichment. A second wave of new residents speak Spanish as their first language: between 1990 and 2003, the state's Latino population more than doubled. A significant number of these residents arrived with limited English-language and -literacy skills, creating new demands and challenges for adult education. Responses slowly emerged from the traditional sources of adult education in the state: the church, nonprofits, the community college system, and the Cooperative Extension Service. Nevertheless, and despite much progress, in the early 2000s North Carolina ranked forty-first in the nation in literacy.