Beginning in 1739, with the arrival of the Argyll Colony, and continuing through the first decades of the nineteenth century, the Cape Fear River Valley was home to the largest settlement of Highland Scots in North America. A majority of these settlers were fluent speakers of their native Gaelic, and the language was used by these immigrants and their descendants in North Carolina until well into the nineteenth century. Gaelic was the language used in many Scottish homes and, more important, in many of the churches in parts of North Carolina's Highland settlement. Several Gaelic place-names are found in the region, the most obvious being Dundarrach in Hoke County, which in Gaelic means "hill of the oak tree." Some familiar words that have Gaelic origins and usage remain in colloquial speech among older citizens of the region, despite the fact that, as a vital language, Gaelic has long since died out.

The first Gaelic-speaking minister to serve in North Carolina was James Campbell, a native of Argyllshire, who came to the Highland settlement in 1758. Campbell was instrumental in founding the sister churches of Barbecue, Bluff, and Longstreet, all of which had Gaelic-speaking congregations. Campbell was joined just prior to the Revolutionary War by at least two other Gaelic-speaking ministers, John MacLeod and John Bethune, both of Skye. Both of these ministers were Loyalists and did not remain in North Carolina following the American Revolution. Later immigrant ministers, including Angus McDiarmid of Islay, John McIntyre of Argyllshire, and Colin McIver of Lewis, among others, continued to serve the Highland settlement by preaching in both Gaelic and English well into the nineteenth century. Several American-born Gaelic speakers were also ordained in a ceremony at Barbecue Church in 1801.

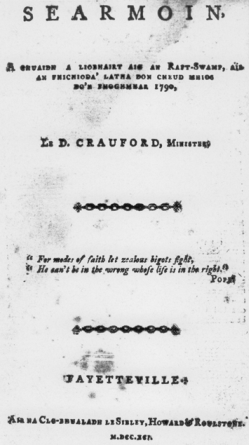

The size and importance of the Gaelic-speaking population was addressed by the Provincial Congress of North Carolina in 1776, when its members addressed the question of publishing pro-Patriot materials in Gaelic. North Carolina holds the distinction of having the first known Gaelic publication in North America: in 1791 the firm of Sibley, Howard, and Rowlstone of Fayetteville published copies of two Gaelic sermons delivered by Dougald Crawford, a native of Arran and former Loyalist chaplain who remained in the Cape Fear region following the American Revolution. In 1826 a copy of Peter Grant's Gaelic Hymnary was also published. Also worthy of note is the fact that the Gaelic newspaper An Gaidheal, of Toronto, had an agency for subscription and correspondence in Lumberton as late as 1871.

In the nineteenth century, many of the Presbyterian churches in what became the Fayetteville Presbytery held two church services, one in English and one in Gaelic, to accommodate their members. This practice was discontinued by many congregations around the time of the Civil War, in part because of cultural assimilation but also because of a decline in newly arriving immigrant Gaelic-speaking Scots. Gaelic services were not completely limited to Presbyterian churches; Daniel White, a converted Baptist from Argyllshire, founded Baptist congregations in Robeson and Scotland Counties in which Gaelic was spoken, and Allan McCorquodale, a Scottish-born Methodist, is also known to have preached in Gaelic to several Methodist congregations in the region. There are a few recorded instances of the use of Gaelic in churches after the Civil War. In all, there were at least 30 congregations throughout the Cape Fear region in which Gaelic services were once held.

Among the significant artifacts of the Gaelic language in North Carolina are the songs of John MacRae, the "Kintail bard," who came to North Carolina just prior to the Revolutionary War. MacRae was a Loyalist, and his fate after the war is unknown. However, the songs that he composed in North Carolina, including his best-known song, "Dean Cadalan Samhach" (Sleep Softly, My Darling Beloved), were transmitted through the Gaelic oral tradition, obviously making several transatlantic trips. Folklorists have found MacRae's songs composed in North Carolina to be known in Scotland, Canada, and even as far away as Australia among Gaelic-speaking communities.