Governor: 1891-1893

See also: Thomas Michael Holt, Dictionary of North Carolina Biography, Louisa Holt

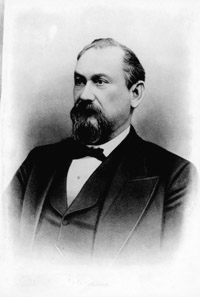

Taking office upon the unexpected death of Governor Daniel G. Fowle, Thomas Michael Holt (1831-1896) employed skills developed as a textile leader to captain the ship of state. The second of Edwin Michael and Emily Farish Holt’s ten children, the future governor was born on July 15, 1831, at Locust Grove, the family home in Orange (now Alamance) County. The Holt family helped to pioneer the textile industry in North Carolina. Young Holt studied at the Caldwell Institute in Hillsborough and entered the University of North Carolina in 1849 but left the next year. With the approval of his father, he sought more practical business experience as a salesman and bookkeeper in a large dry goods store in Philadelphia.

Changes in the structure of his textile business prompted E. M. Holt to call his son home in 1851 to run the mill on Alamance Creek. According to the elder Holt’s diary, it was his son who, employing the techniques of a French designer, discovered the dyeing process leading to the famous “Alamance Plaid.” Thomas Holt married Louise Moore in 1855; they had six children. Throughout the Civil War Holt supplied clothing and textiles to the Confederacy. After the war he and his partner, Adolphus Moore, built a larger factory on the Haw River that eventually employed 175 persons and supported a village of forty homes, a school, and a church.

Holt had been affiliated with the Whig Party in the antebellum years but listed himself as a Democrat while serving as Alamance County commissioner, 1872-1875. He won election to the 1876-1877 session of the state Senate and served three terms in the North Carolina House of Representatives beginning in 1883. He was speaker of the house during the 1885 session. Running on the ticket with Daniel G. Fowle in 1888, he was elected lieutenant governor.

Long interested in education, Holt, prior to serving as governor, promoted the establishment of the Agricultural and Mechanical College (present North Carolina State University) and served on the boards of trustees at the University of North Carolina and Davidson College. He supported establishment of a normal school for white women (now the University of North Carolina at Greensboro), college level facilities for blacks (present-day North Carolina A. & T. State University and Elizabeth City State University were chartered by the 1891 legislature), and a new state institution for the deaf at Morganton. He advocated additional funding for Oxford Orphanage, the state mental institutions, and an expansion of the common schools. Holt also supported the growing movement to return elective control of local governments to the residents by repealing the law that gave the legislature the power to select justices of the peace.

Given a strong start by a revolutionary “farmers” legislature that concluded work just before he assumed office in 1891, the governor achieved virtually all of his goals. The people regained control of local governments; an increased tax rate assisted the public schools; and the appropriations for the state hospitals and the university were increased. As a former president of the North Carolina Railroad, however, Holt did not favor the creation of an unrestrained railroad commission. His thirteen years as president of the Grange and a long-time association with the State Fair afforded him an understanding of the farmers’ viewpoint.

Holt’s health weakened during his administration and he chose not to run for reelection in 1892. He retired to private life but could manage his interests only on a part-time basis. A Presbyterian, he died on April 11, 1896, at his home on Haw River and was buried in Linwood Cemetery in Graham.