See also: Exploring North Carolina: History of Maps, Surveying, Cartography and Cartographers, North Carolina Maps from NCpedia Student, and Maps from NCpedia Student

The story of cartography, or mapmaking, in the North Carolina region may have begun with the Vinland map of 1440. Although its authenticity has been questioned, the map gives ample evidence, as tested by renowned scholars, that the East Coast of the New World from Newfoundland to Cuba was visited by Europeans well before Columbus. This was when North Carolina, as it is defined today, was known as "Nova Albion."

The early maps of the area that was to become North Carolina resulted from the mapping and compilation of information of the coast by ancient mariners and explorers. Mapping and recording observations from the deck of a bouncing ship were not easy tasks. The early maps were generally nothing more than rough sketches of the coastline with latitudinal measurements taken with a backstaff, distances measured with an alidade, and depths taken with a lead line. Surveying by the more modern method of triangulation came into practice with Thomas Harriot on the second of the Raleigh voyages in 1585-86, although triangulation was used to make maps as early as 1535 by Gerhard Mercator. Early maps did not usually have longitude, nor were they very accurate, sometimes intentionally so. Still, some of the maps were quite good (especially John Smith's map of 1612).

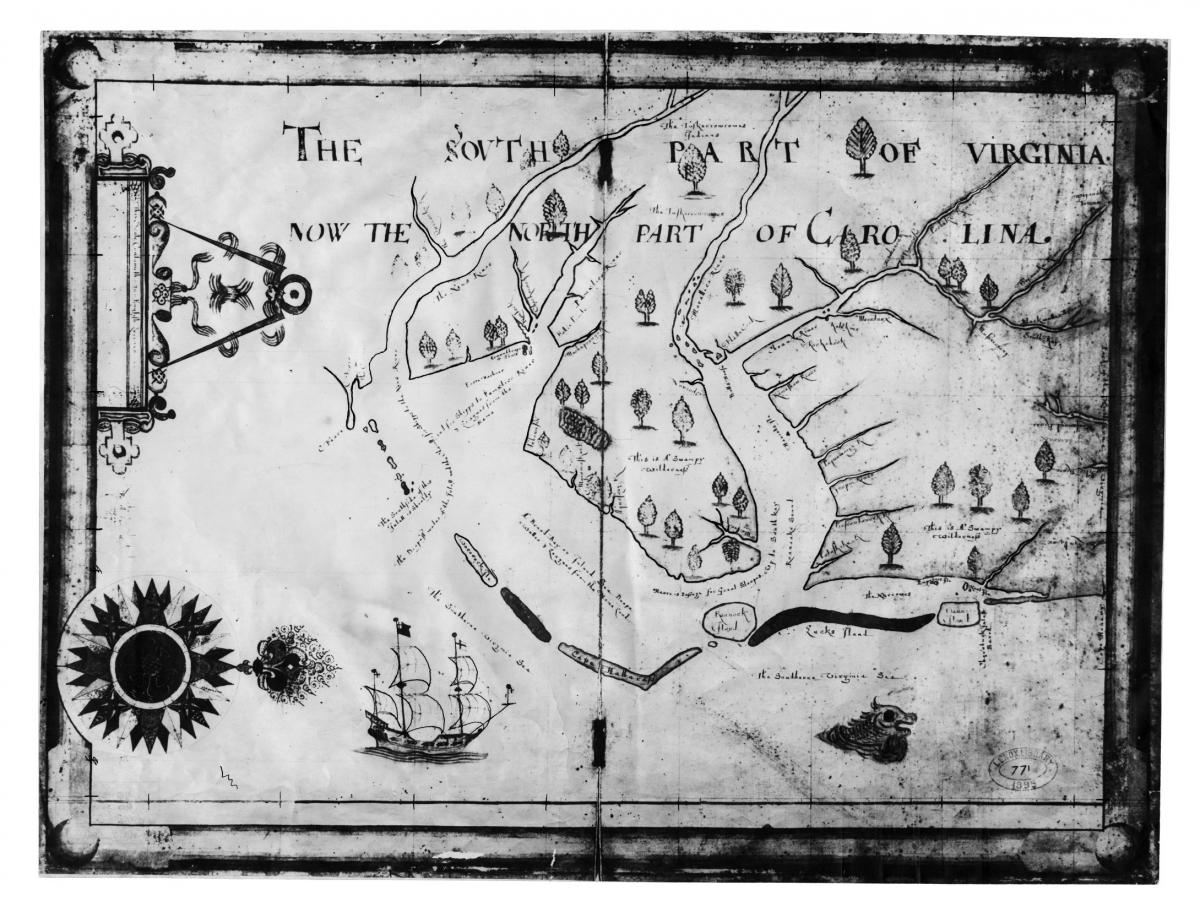

Much of the exploration and discovery of America in the late fifteenth century and the sixteenth century was undertaken to find a shorter route to the Far East, and many maps were used to market that theme. Indeed, often a map's accuracy was secondary to its elaborate beauty. Such are the maps of the Thames School. In particular, Nicholas Comberford's map of 1657 shows a very generalized North Carolina coastline with scattered trees inland and Pamlico Sound described as a broad bay or inland sea. The Comberford map contains the earliest evidence of permanent European settlement of the region that became North Carolina. This colored manuscript map on vellum in the National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, England, is titled "The South Part of Virginia." Another one in the New York Public Library, otherwise virtually identical, has added in a later hand, "now the north part of Carolina." Shown between the Roanoke River and Salmon Creek is "Batts House," the trading post/home of Nathaniell Batts, believed to have been the first permanent settler of the colony.

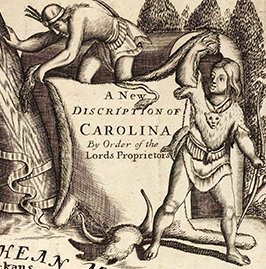

By the mid-seventeenth century, maps were used to describe the virtues of America and other places of the New World. John Ogilby's atlas of America in 1671 and John Speed's map and description in 1676 are wonderful examples of early marketing. The early settlement of North Carolina, known as "Virginia" in 1675, began in the Albemarle Sound area and continued into the early 1700s. William Hack's map of 1684 shows the Appalachian Mountains, as more was being learned about the interior of America. Exploration of the interior portion of North Carolina was soon followed by settlement inland. John Lawson's map of 1709 and his surveying commentary attest to the acclimation of explorers to the landscape. More and more place names were being mapped and recorded. Place names began to appear on the maps in vastly greater density, and the descriptions on the maps were in much better detail.

In colonial times, as settlements were located more inland, explorers established trails, most of which were borrowed from the Indians. Surveyors following by foot or on horseback trotted across the frontier to divide up the land established by the king. Edward Moseley's map of 1733 added greatly to the understanding of the interior of North Carolina, as did James Wimble's 1738 map of the coast. John Collet's map of 1770 gives the names of settlers, and details such as shoals, swamps, and roads appear on the 1775 map of Henry Mouzon. Joshua Fry and Peter Jefferson's map of the same year shows the name and location of stores, ferries, and roads. The North Carolina area was finally becoming settled.

As the United States became more spatially and politically organized after the American Revolution, the government took on the responsibility of mapmaking. Surveying and mapping by the government began by act of the Continental Congress on 20 May 1785, and the Board of Engineers was created in the early 1800s. The mapping of the coasts, harbors, and rivers became very important to the government. Thus, the need for individual surveyors, mapmakers, and the like became practically obsolete in the private sector, and they moved on to do mapping in the western United States, Canada, South America, Africa, and Pacific Coast.

Mapping programs by government agencies, particularly the U.S. Geological Survey, continued throughout the twentieth century and into the twenty-first century. The U.S. Coast and Geodetic Survey had a continuous chart-updating program, and the U.S. Corps of Engineers continued its reconnaissance survey work. Major oil companies began to produce state road maps, and the North Carolina Highway Commission started its county road map series. Using these maps, Garland P. Stout researched old maps, deeds, and other records and recorded information on the North Carolina county maps. Each county map shows the location of post offices, schools, churches, gristmills, mine sites, and abandoned settlements.

Efforts to map soils began after World War I and continued throughout the century. The U.S. Soil Conservation Service, the North Carolina Soil Conservation Service, and the North Carolina Department of Natural Resources and Community Development completed the mapping program by 1978. North Carolina was also covered by U.S. Geological Survey topographic maps with the assistance of the North Carolina Department of Natural Resources and Community Development.

With the advent of satellite imagery and computerized databases, mapping in North Carolina became permanently altered by the technical revolution. Mapping is now accomplished with a computer using a geographic information system (GIS), and place names are found in the geographic names information system (GNIS).

Cartographers or Publishers of Maps of the North Carolina Area |

|

Early Maps |

|

|

1440? |

Vinland |

|

1500 |

Juan de la Cosa (sailed with Columbus) |

|

1507 |

Martin Waldseemuller |

|

1526 |

Juan Vespucci (nephew of Amerigo Vespucci) |

|

1529 |

Diego Ribero (or Diogo Ribeiro) |

|

1529 |

Giovanni da Verrazano (from voyage in 1524) |

|

1538 |

Gerhard Mercator |

|

1542 |

John Rotz |

|

1550 |

Pierre Desceliers |

|

1558 |

Diogo Homem |

|

1560 |

Baptista Agnese (Portolan Atlas) |

|

1562 |

Diego Gutierez |

|

1567 |

Alonso de Santa Cruz |

|

1569 |

Gerhard Mercator |

|

1580 |

John Dee |

|

1582 |

Michael Lok |

|

1584 |

Ortelius-Chives |

Elizabethan-Era Maps |

|

|

1585 |

John White (watercolor drawing) |

|

1587 |

John White (probably drawn by Thomas Harriot and published in 1590 by Theodor de Bry) |

|

1590 |

Ortelius |

|

1590 |

John White (published by de Bry, probably compiled from earlier maps) |

|

1591 |

Theodor de Bry (probably drawn by Jacques le Moyne de Morgues) |

|

1597 |

Cornely Van Wytfliet (used White as a partial source) |

|

1605 |

Willem Janszoon Blaeu |

|

1606 |

Gerhard Mercator–Jodocus Hondius |

|

1608 |

John Smith |

|

1611 |

Velasco |

|

1612 |

Grauen B. Wm. Hole (probably from Smith) |

|

1615 |

Cornely Van Wytfliet |

|

1624 |

John Smith |

|

1630 |

Gerhard Mercator |

|

1640 |

Blaeu (based on Mercator-Hondius map of 1606) |

|

1646 |

Robert Dudley |

|

1647 |

Johannes Jansonius |

|

1651 |

John (or Nicholas?) Farrer (or Ferrar?) |

|

1651 |

John Goddard (or Gaddard) (possibly used Farrer’s map as source) |

|

1653 |

Juan Jansonio (or Jansonius) |

|

1656 |

Sanson (or Janson) |

|

1657 |

Nicholas Comberford (Thames School) |

|

1660 |

Jan Jannsson |

|

1662 |

John Locke |

Proprietary Period Maps |

|

|

1666 |

Horne (compilation of explorations published by Hilton) |

|

1667 |

John Farrer |

|

1670 |

Augustine Herman (very near North Carolina area) |

|

1671 |

John Locke (from Spanish sources) |

|

1671 |

John Ogilby (used Locke’s map and Lederer’s information) |

|

1672 |

Blome and John Ogilby |

|

1672 |

John Lederer (shows first town “Sapon” on Roanoke River) |

|

1672 |

John Ogilby–James Moxon (Lords Proprietors order) |

|

1673 |

Robert Morden and William Berry |

|

1676 |

Lamb (probably from John Speed) |

|

1676 |

John Speed (similar to Ogilby’s map of 1671) |

|

1676 |

Capt. John Wood (used Morden and Berry as source) |

|

1677 |

Joel Lancaster (Thames style) |

|

1679 |

Joel or James Lancaster |

|

1682 |

Joel Gascoyne (Gascoigne) |

|

1682 |

Joseph (or James?) Moxon |

|

1684 |

William (or John) Hack |

|

1684 |

Maurice Mathews |

|

1685? |

John Thornton, Morden and Lea |

|

1686? |

John Thornton and Fisher |

|

1687 |

John Thornton |

|

1695 |

John Thornton and Morden |

|

1695 |

Willdey |

|

1696 |

Guillaume De Lisle |

|

1696 |

John Sanson (Pierre Mortier was probably publisher using Thorton and Morden under Sanson’s name) |

|

1709 |

John Lawson |

|

1715 |

Moll |

|

1718 |

Guillaume De Lisle |

|

1720 |

Moll |

|

1720 |

Van Kenlen |

Royal Colony Period, Revolutionary, and Postrevolutionary Maps |

|

|

1729 |

Pierre or Peter Vander Aa |

|

1732 |

Hinder |

|

1733 |

Edward Moseley |

|

1733 |

James Wimble |

|

1736? |

Moll |

|

1737 |

Brickell |

|

1738 |

Edward Moseley |

|

1738 |

James Wimble |

|

1751 |

Joshua Fry and Peter Jefferson (two maps) |

|

1755 |

Dalrymple (revised from Fry and Jefferson) |

|

1768 |

Thomas Jefferies (or Jefferys) |

|

1770 |

John Collet |

|

1775 |

Henry Mouzon |

|

1777 |

John Gascoigne |

|

1792 |

Dubibin (from a map dated 1756) |

|

1794 |

Henry Mouzon and others |

|

1795 |

Henry Mouzon |

Nineteenth-Century Maps |

|

|

1808 |

Jonathan Price–John Strother |

|

1820 |

Hamilton Fulton |

|

1833 |

John MacRae (or Mac Rae)–Robert H. B. Brazier |

|

1843 |

John Calvin Smith |

|

1856 |

Adam and Charles Black |

|

1861 |

Bachmann |

|

1861 |

J. H. Colton |

|

1882 |

Kerr-Cain |