Established: 1956, 1999

GPS Coordinates: 36.393564,-81.468012

Size: 975 acres

Park Area History and Geology

Mount Jefferson lies along the drainage divide between the north and south forks of the New River—one of the oldest rivers in North America and in the world. This drainage system had an important influence on the size and shape of the mountain.

The mountain and its nearby peaks are remnants of a once lofty, mountainous region that existed throughout much of the western part of the state. Weathering and the erosive action of streams throughout millions of years wore away the softer, less resistant rocks. More resistant rocks, including the amphibolite and metagraywacke of Mount Jefferson, were slower to erode. These and other rocks comprise the peaks standing above their surrounding plateau.

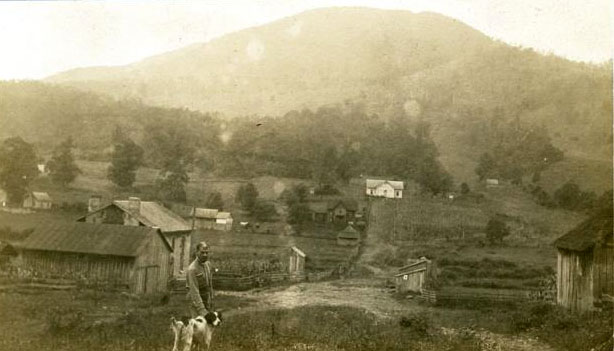

Though there is no evidence of permanent Native American settlements in the Ashe County area, game was plentiful and both the Cherokee and the Shawnee claimed it as a hunting ground. The first settlers in the area were from Virginia. Few North Carolinians, other than adventurous individuals like Daniel Boone, had ventured westward beyond the Blue Ridge Mountains.

Before the American Revolution, Mount Jefferson was known as Panther Mountain, perhaps because of a legend that tells of a panther that attacked and killed a child there. Area residents gave the mountain other names until 1952 when Mount Jefferson received its official name. The mountain's name was chosen in honor of Thomas Jefferson and his father, Peter, who owned land in the area and surveyed the nearby North Carolina-Virginia border in 1749. Around the time of the Civil War, legend holds that the "caves" beneath Mount Jefferson's ledges served as hideouts for freedom-seeking enslaved people traveling to freedom on the Underground Railroad.

Park Development

By the 1930s people began to take an interest in creating widespread access to the mountain. The site as a park had its beginnings when the Works Progress Administration constructed a two-mile road to the summit. In 1939, local officials sought to have the road improved, but the state could not provide funds for a private road. In order to get needed road improvements, two local residents who owned land on the mountain -- H.C. Tucker and J.B. Hash -- donated 26 acres, and the site became a state wayside park.

In 1942, citizens petitioned the General Assembly to take the park as a state park, but the effort failed. In 1955, attempts were made again to establish the park as a state park; they failed once again due to legislation passed that year specifying a minimum size of 400 acres for state parks. Citizens then began campaigns to raise funds and land donations. By 1956 300 acres had been obtained by gift and an additional 164 acres by fundraising, sufficient to establish a state park. The mountain's named was changed to Mount Jefferson at the establishment of the state park.

In 1974 the park was designated by the federal government as a National Natural Landmark, recognizing its natural heritage with undisturbed red oak forests and as a key example of existing oak-chestnut forests in the Southeast. The state changed its designation to a state natural area in 1999.

Park Ecology

The slopes and summit of the mountain are home to a diverse population of trees, shrubs and wildflowers. This large variety of interesting and unusual plants qualified the area for designation as a national natural landmark by the National Park Service in 1974.

The forests of the area vary with the altitude and the direction of the slope. At altitudes above 4,000 feet, an oak/chestnut forest dominates the slopes facing south, east and west. This forest is one of the best examples of its type in the southeastern United States. Beneath the canopy of oak is an understory of Catawba rhododendron, mountain laurel, flame azalea and dogwood. Wildflowers include trillium, pink lady slipper and false lily of the valley.

Until the early 20th century, American chestnut trees were abundant in the area. The chestnut's rot-resistant wood was immensely valuable to early settlers for the construction of buildings and fences, and its large, sweet nuts provided food for humans and animals. Tragically, the chestnut blight, introduced from Europe in 1910, destroyed the species here and elsewhere. At the summit of Mount Jefferson, ghostly trunks stand; sprouts rise from the diseased roots and thrive until maturity when they become susceptible to the blight.

On the north slopes, a cove forest includes red maple, yellow birch, tulip tree and basswood. In the understory are mountain ash, prairie willow, black huckleberry and mountain pepperbush. Hobblebush, mayapple, blue bead lily and other shrubs and herbs cover the forest floor. On the slopes below Luther Rock is a stand of big-toothed aspen trees. The big-toothed aspen is primarily a northern plant, found in North Carolina only in Ashe and Haywood counties. Trees growing on the northern ridges and slopes of Mount Jefferson are gnarled and dwarfed, averaging only about 20 feet. Their growth has been stunted by exposure to strong northerly winds and heavy loads of ice in winter.

The animal life of the natural area has not been as well studied as the plant life but is typical of the western part of the state. Red squirrels, locally known as “boomers,” live in forests near the peak. Several species of small mice, including deer mice, and southern red-backed voles are also common.

Bird life in these high-altitude forests includes several species not seen at lower elevations. Lucky visitors may catch a glimpse of a red-tailed hawk, the most common hawk in the area. Chestnut-sided warblers, Canada warblers and black-throated blue warblers, as well as rose-breasted grosbeaks, slate-colored juncos and white-breasted nuthatches nest in the woodlands. Their melodies are often heard with the song of the veery at dusk and dawn. The wing beats of flushed ruffed grouse often surprise hikers along the trail.

The park's mature deciduous forests are home to many common mammals, including gray squirrels, southern flying squirrels, eastern chipmunks, red foxes, raccoons and Virginia opossums. Shrews, moles and mice also make their homes in the middle altitudes. Woodchucks and an occasional white-tailed deer inhabit the forest edges. Reptiles, such as skinks and small snakes, travel in and around rotting logs and other places offering food and seclusion.