See also: American Association of University Women; Equal Rights Amendment; League of Women Voters; North Carolina Equal Suffrage Association; Women Suffrage.

Part i: Introduction; Part ii: Women's Roles in Precolonial and Colonial North Carolina; Part iii: Women in the Revolutionary Era and Early Statehood; Part iv: Life in Antebellum North Carolina; Part v: Secession and Civil War; Part vi: Women Help Shape the New South; Part vii: Women Earn the Right to Vote; Part viii: Activism and the Expansion of Women's Opportunities and Public Influence; Part ix: References

The coming of the Civil War placed all white women in the forefront of supporting the Confederate cause. Women ran the farms, plantations, and businesses while men left to fight in increasingly bloody battles. A diary kept by Halifax County plantation mistress Kate Edmondston, and published more than a century after the war as Journal of a Secesh Lady, recorded the impact of the war on women in the state. Women had to rely on themselves and make important decisions. Some welcomed the challenge and independence, but others found it stressful and resented the demands placed on them.

North Carolina's secession elicited immediate and enthusiastic support from many of its women, who worked together to make uniforms, tents, cartridges, bandages, and other military supplies. Some worked in hospitals, organized food drives, and raised funds for war equipment. They wrote patriotic poetry and fiercely criticized southern men who failed to enlist. One woman, Sarah Pritchard Blalock, disguised herself as a man and joined the Twenty-sixth North Carolina Regiment to remain near her husband. As Union troops advanced into eastern North Carolina, many women and children became refugees dependent upon friends and strangers for shelter during times of inflation and food shortages. Public schools for the first time employed more women as teachers than men, at a time when many women needed the income.

Huge numbers of North Carolinians lost family members during the war. The state sent more soldiers to fight for the Confederacy than any other state, and it sustained the greatest number of casualties. Yeoman families in particular suffered as the war dragged on. Facing starvation (flour that had cost $18.00 a barrel in 1862 jumped to a price of $500 a barrel in 1865), they resisted Confederate authority. Some women staged food riots to seize flour and other commodities. They wrote heartfelt letters to Governor Zebulon B. Vance demanding an end to the war and assistance in feeding their families. Yeoman women also wrote letters to their men in the army urging them to come home. By 1864 many North Carolina soldiers had deserted to help their families. The state's Home Guard shot deserters and did not hesitate to torture yeoman women to try to force them to reveal where their male relations were hiding. The protection accorded southern ladies did not apply to women of the yeoman class in many instances.

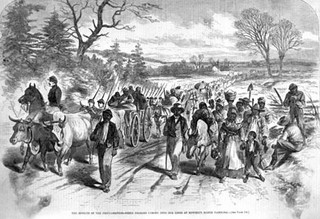

The work of enslaved women also fed and clothed the Confederacy. This work was often coerced and demanded of enslaved people against their will. Enslaved women who lived near towns occupied by northern troops fled to Union lines. In New Bern and other areas under Federal control, they worked for northern troops as cooks and laundresses and ran boardinghouses. They set up schools to educate black children and helped create new communities such as James City. When the war ended, many enslaved people quickly fled plantations in search of better lives and opportunities than those offered under their enslavers.