Part i: Introduction; Part ii: Women's Roles in Precolonial and Colonial North Carolina; Part iii: Women in the Revolutionary Era and Early Statehood; Part iv: Life in Antebellum North Carolina; Part v: Secession and Civil War; Part vi: Women Help Shape the New South; Part vii: Women Earn the Right to Vote; Part viii: Activism and the Expansion of Women's Opportunities and Public Influence; Part ix: References

See also: American Association of University Women; Equal Rights Amendment; League of Women Voters; North Carolina Equal Suffrage Association; Women Suffrage.

Women's reactions to the Confederacy's defeat reflected racial, gender, and class differences. There were 25,000 more women than men in North Carolina at the end of the war. Widowed, married, or single, women struggled with poverty. Many accepted paid work to support themselves or their families for the first time. North Carolina's 1868 constitutional convention wrote a new constitution that improved married women's property rights (which also had the effect of helping husbands by protecting property from creditors). More women in the state entered college to improve their knowledge and skills. Educated women, both black and white, turned a critical eye on society and organized women's voluntary associations to promote social change.

Black women sought to reunite families, educate their children, and work with their husbands to build better lives for themselves and their race. Many found that their only chance to work-for poor wages and under harsh conditions-was in domestic service, agricultural labor, or the state's emerging tobacco factories. They were not allowed into the textile mills of the New South, which hired only whites. By 1890 more than 42 percent of black women worked outside their homes, as compared to about 15 percent of white women.

Self-sufficient farms declined with the emergence of a cash crop economy in the 1880s. These crops fed the tobacco and cotton factories, but as a result farm families grew less food for themselves and incurred more debt to merchants who charged high prices and interest. Women, black or white, who had viewed themselves as partners in the farming enterprise felt undervalued as their unpaid contributions lost value in the family economy. Many farmers became so indebted that they lost their farms. By 1890 one-third of white farmers and nearly three-quarters of black farmers in North Carolina were tenants or sharecroppers.

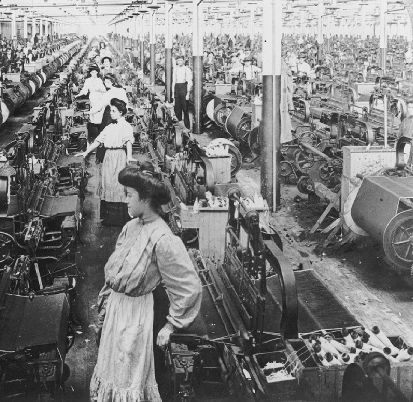

At the same time, industry expanded in the state. By 1904 North Carolina cotton mills contained half the looms and spindles in the South. Mill owners needed cheap local labor to run the machinery. They welcomed white women and children as workers because they could pay them less and because women and children rarely challenged male authority. By 1880 women and children composed 75 percent of the state's mill workers. Durham's tobacco factories employed women in larger numbers, too, offering work to black women as well as white. By 1910 North Carolina's 272,990 female workers represented the highest percentage of working women (34.2 percent) in the nation. Among those working in the lower classes, about half worked in agriculture, and the other half worked as domestic servants or in cotton mills and tobacco factories.

Discontented black and white farm families joined Republicans and agrarian reformers in the Farmers' Alliance and Populist Party in the 1880s and 1890s to challenge entrenched political and business interests in North Carolina that controlled industry and farm prices. About 25,000 women joined the Farmers' Alliance in the state. They pressed for reforms such as the establishment and funding of public schools and colleges for black and white women with some success. White supremacy campaigns launched by the Democrats in 1898 and 1900 limited interracial cooperation, however, until the end of Jim Crow laws, disfranchisement, and segregation in the 1950s and 1960s.

Following the Civil War, wealthy white women faced diminished income and an independent black labor class. The eldest generation, who had profited most from the labor of enslaved people, largely rejected the aspirations of black families. The younger generations of elite white women proved more assertive in building new lives. Some preferred being single and working to support themselves. North Carolina women such as Mary Bayard Clarke and Frances Christine Fisher Tiernan became writers who achieved literary success in the 1870s and 1880s. Women used organizational skills developed during the Civil War to provide service to the state. Raleigh women in May 1866 formed the Wake County Ladies' Memorial Association to establish a cemetery for Confederate dead. In May 1867 they opened one of the first Confederate cemeteries in the South. Women in many other towns did the same. Elite young women who married did their own housework, often with labor-saving devices such as stoves and washing machines or with the help of black women servants. They enjoyed their success in creating modern households.

The overwhelming number of elite working women accepted jobs as teachers in public and private schools and eventually changed the face of instruction in North Carolina. By the 1930s, women made up 80 percent of the state's teaching population. New institutions of higher learning were established, such as the State Normal and Industrial College for white women in Greensboro (now UNC-Greensboro) and Saint Augustine's College for black men and women in Raleigh. Careers as nurses or doctors, librarians, or other professionals became possible, although less than 3 percent of the state's working women were engaged in professional work in 1900. This percentage increased to 10 percent by 1940.

Many women were led by their changing self-image to volunteer in organizations that would benefit the public welfare. White and black women joined the Woman's Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) in the 1880s and worked together to combat alcohol abuse. Black women organized the WCTU Number 2 in 1889, in which they set priorities not only for temperance but also for improving the legal status of their race. In 1908 temperance women achieved victory when North Carolina voters approved statewide Prohibition.

White women's patriotic and memorial groups, such as the United Daughters of the Confederacy, were organized in the 1890s during a period of increased racial strife. These groups controlled the content of textbooks, fostered the literature of the Lost Cause, and preserved class and racial authority. They also participated in white supremacist campaigns that led to the disfranchisement of black men in 1900.

By the twentieth century, North Carolina's organized women confidently advocated public reform. They were not radical feminists. They believed educated women had a duty to study their society, identify problems, and implement solutions. They joined the North Carolina Federation of Women's Clubs (NCFWC), the YWCA, church societies, and temperance groups and set goals for the state's future. The NCFWC, from 1902 on, proved pivotal in persuading the General Assembly to pass welfare legislation for improved sanitation, public libraries, better schools, and much more. The group successfully campaigned in 1913 to have women placed on public school boards, even though women were not yet allowed to vote. Despite the achievements accomplished jointly with black women in groups such as the North Carolina Federation of Colored Women's Clubs, most white organized women remained silent about the treatment of blacks. Not surprisingly, urban black women supported civic reform to help their race as well as their neighborhoods. Leaders such as Charlotte Hawkins Brown challenged white women's unquestioning acceptance of the inferiority of the black race.