North Carolina claims several contentious superlatives: first in flight (disputed by Ohio since Orville and Wilbur Wright lived in Dayton, Ohio), the first state university (disputed by Georgia since its university was chartered first, though North Carolina's opened first), and the first declaration of independence, though most historians dispute the veracity of the Mecklenburg Declaration of Independence. Even with its questionable credentials, the date of the "Meck-Dec" still adorns North Carolina's state flag. The other date on the flag, April 12, 1776, however, honors a first that no other state can claim, the "Halifax Resolves." Though it was not an outright declaration of independence from Great Britain, this resolution, which was unanimously passed at the fourth Provincial Congress meeting in Halifax, North Carolina, was the first official action in which a colony authorized its delegates to the Continental Congress to vote for independence.

Just eight months earlier, North Carolina's official attitude toward independence was a bit more ambivalent. Facing increasing uncertainties and dealing with the divided loyalties of its populace, the third Provincial Congress issued an "Address to the Inhabitants of the British Empire." This statement, which sought to justify congress's actions (such as stockpiling weapons, raising units of soldiers, and preparing for self-government), denied that the colony desired to separate from Great Britain. It claimed allegiance to the crown, asserted that Parliament was at fault for passing undesirable legislation, and reiterated the colony's desire to return to the relationship that existed between Great Britain and the American colonies in the years prior to the French and Indian War.

From August 1775 to April 1776, the deteriorating situation in North Carolina and other colonies changed how many North Carolinians and their delegates to the provincial congress viewed their relationship with Great Britain. Following the Battles of Lexington and Concord, King George III declared the colonies to be in a state of rebellion and withdrew his protection from the colonists. In January 1776, royal governor Josiah Martin issued a call for loyalist troops to assemble and rendezvous with a contingent of the British army that was sailing for North Carolina's coast. Though patriot militia and Continental Line soldiers intercepted the loyalists and routed them on February 27, 1776, at the Battle of Moore's Creek Bridge, the skirmish still sent shock waves through the province. In addition, British agents continually worked to incite Native Americans, including the Cherokee, along the colony's frontier, while along the coast, the British navy maintained several war ships. These events and several others forced North Carolina's patriot leaders to the conclusion that reconciliation on amiable terms was no longer possible.

After the Battle of Moore's Creek Bridge, the fourth Provincial Congress convened in Halifax on April 4, 1776. Over the first few days, the congress organized itself and formed committees to oversee aspects of the province's government and military preparations. On April 8, 1776, it created a select committee to consider the "Usurpations and Violences attempted and committed by the King and Parliament of Britain against America, and the further Measures to be taken for frustrating the same, and for the better Defence of this Province." Four days later, on April 12, the group, which consisted of Thomas Burke, Cornelius Harnett (chairman), Allen Jones, Thomas Jones, John Kinchen, Abner Nash, and Thomas Person, presented a report detailing British atrocities and American responses. The committee believed that further attempts at compromise and reunion would fail, and they offered the following resolution:

That the Delegates for this Colony in the Continental Congress be impowered to concur with the Delegates of the other Colonies in declaring Independency, and forming foreign Alliances, reserving to this Colony the sole and exclusive Right of forming a Constitution and Laws for this Colony, and of appointing Delegates from Time to Time, (under the Direction of a general Representation thereof) to meet the Delegates of the other Colonies, for such Purposes as shall hereafter be pointed out.

The full congress took the recommendations into consideration and unanimously approved of them. The resolution was immediately copied and sent to Philadelphia, where Joseph Hewes, a member of North Carolina's delegation, shared it with other American representatives. Soon thereafter, other colonies followed North Carolina's lead, and the foundation was laid for the summer of 1776.

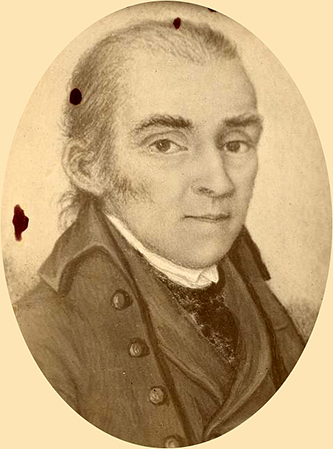

Portrait of Allen Jones, a member of N.C.'s Fourth Provincial Congress

Portrait of Allen Jones, a member of N.C.'s Fourth Provincial Congress