Deaths in the Civil War

In all, historians estimate that about 620,000 Americans died in the Civil War. That's almost as many as have died in all other U.S. wars combined:

|

(a) as of April 2009. (b) as of May 2009. |

||

|

War |

Dates |

U.S. deaths |

|---|---|---|

|

Revolution |

1775-1783 |

4,000 |

|

War of 1812 |

1812-1815 |

2,000 |

|

Mexican-American War |

1846-1848 |

13,000 |

|

Civil War |

1861-1865 |

618,000 |

|

Spanish-American War |

1898 |

2,000 |

|

World War I |

1917-1918 |

112,000 |

|

World War II |

1941-1945 |

405,000 |

|

Korean War |

1950-1953 |

54,000 |

|

Vietnam War |

1959-1975 |

58,000 |

|

Persian Gulf War |

1991 |

300 |

|

Afghanistan War |

2001- |

600 (a) |

|

Iraq War |

2003- |

4,300 (b) |

The numbers are especially shocking when you remember that the population of the United States in 1860 was only 31,443,321 -- which means that nearly two percent of the U.S. population died in the Civil War.

Both sides in the conflict lost about the same fraction of their troops -- 23 or 24 percent -- so one soldier in four died.

|

Union |

Confederacy |

Total |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

Deaths |

|||

|

Death from wounds |

110,070 |

94,000 |

204,070 |

|

Death from disease |

249,458 |

164,000 |

413,458 |

|

Total deaths |

359,528 |

258,000 |

617,528 |

|

Total death rate |

23% |

24% |

23% |

|

Wounded |

|||

|

Wounded |

275,175 |

~100,000 |

~375,000 |

|

All casualties |

|||

|

Totals |

634,703 |

~358,000 |

~992,703 |

Individual Battles

The following table lists battles with more than 20,000 casualties. Here, "casualties" includes killed, wounded, captured, and missing. Note that estimates of casualties vary -- often widely -- and we've tried to give the most commonly cited numbers or ranges, rounded off for simplicity.

Regardless of the detail, the scale of the carnage is simply incredible. As many Americans died in a single day at Antietam as died in the entire War for Independence. In the Normandy Landings on "D-Day," June 6, 1944 -- the most famous battle of World War II -- the U.S. suffered 6,600 casualties, yet that number pales in comparison with the deaths at Gettysburg.

|

Battle |

Dates |

Union |

Confederate |

Total casualties |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Forces |

Casualties |

% |

Forces |

Casualties |

% |

|||

|

Gettysburg |

July 1863 |

94,000 |

23,000 |

24% |

72,000 |

23,000 |

30% |

46,000 |

|

Chickamauga |

Sept. 1863 |

60,000 |

16,000 |

27% |

65,000 |

18,500 |

28% |

34,500 |

|

Chancellorsville |

May 1863 |

134,000 |

17,000 |

13% |

61,000 |

13,000 |

21% |

30,000 |

|

Spotsylvania Court House |

May 1864 |

100,000 |

18,000 |

18% |

52,000 |

12,000 |

23% |

30,000 |

|

The Wilderness |

May 1862 |

102,000 |

18,500 |

18% |

61,000 |

7,500-11,500 |

12-19% |

26,000-30,000 |

|

Second Bull Run (Second Manassas) |

Aug. 1862 |

62,000 |

14,500 |

23% |

50,000 |

9,500 |

19% |

24,000 |

|

Antietam |

Sept. 1862 |

87,000 |

12,500 |

14% |

45,000 |

10,500 |

23% |

23,000 |

|

Stones River |

Dec. 1862; Jan. 1863 |

43,500 |

13,000 |

30% |

38,000 |

10,000 |

26% |

23,000 |

|

Shiloh |

April 1862 |

67,000 |

13,000 |

19% |

44,500 |

10,500 |

24% |

23,500 |

The Reasons

There were several reasons for the huge numbers of casualties in the Civil War. They had to do not only with the way battles were fought, but with what happened to soldiers afterward.

Technology

Military technology improved tremendously in the middle of the nineteenth century. In particular, new guns could be loaded faster or fire multiple rounds without being reloaded. The first revolver was invented in 1836, and breech-loading rifles could be loaded from the back, letting a solider fire more rounds per minute. (Compare this to what a Revolutionary soldier had to do.)

The minie ball made infantry fighting especially deadly. A rifled barrel spins the bullet and thus makes it fly straighter -- think of the spiral on a football -- but older rifles had to be loaded by slowly stuffing the bullet through the grooves of the barrel, which was not practical for someone in the heat of battle. The minie ball was smaller than the diameter of the barrel, and so a soldier could load his rifle simply by dropping the minie ball down the barrel. When the rifle was fired, the powder in the cartridge burned, producing hot gas that caused the minie ball to expand and fill the barrel. The grooves in the base of the ball then fit into the grooves of the barrel.

The combination of speed and accuracy meant that infantry fighting was deadlier than ever before. A competent marksman could hit his target from 200 yards away, and the minie ball traveled fast enough to shatter bone on impact. The balls were also soft, not hard-jacketed, and so they spread on impact, making a larger hold and causing more damage and bleeding.

Strategy

The rifle and minie ball gave a new advantage to the defense in a battle. Older muskets -- without rifling -- had a much smaller range, and allowed soldiers to get close enough together to fight hand to hand, with bayonets. In the Civil War, armies engaged each other at greater distances. Artillery also became less important, because cannon crews could be picked off by distant marksmen. As a result, an army with a good position could simply mow down enemy soldiers making a frontal assault.

Yet most generals in the Civil War clung to older theories of warfare that valued offense rather than defense -- in part because that was what they had learned at West Point, and in part because their sense of honor demanded a willingness to fight. But frontal assaults, however heroic they might sound in books, were suicidal now. In Pickett's Charge at the Battle of Gettysburg, almost 6,000 Confederate soldiers were killed or wounded as they advanced uphill over a mile of open ground toward entrenched Union positions.

Disease

If you look at the table above, you'll see that twice as many men died of disease as were killed in battle. So many men living in close quarters, under great stress and often with poor nutrition, were subject to epidemics. Diseases such as measles, mumps, and whooping cough swept through the camps. Near swamps, mosquitoes brought malaria. And already-weakened soldiers who caught a common cold often developed pneumonia.

But the biggest cause of disease was a lack of sanitation. Open latrines, decomposing food, and manure attracted disease-carrying insects and contaminated drinking water. The Union army reported that more than 995 out of every 1,000 men contracted chronic diarrhea or dysentery during the war. Typhoid fever, caused by salmonella bacteria in food and water, was responsible for as many as a quarter of all non-combat casualties in the Confederate army.

Disease was, sadly, an expected part of war in the nineteenth century. Not until World War II would the U.S. fight a war in which more soldiers died of battle wounds than of disease.

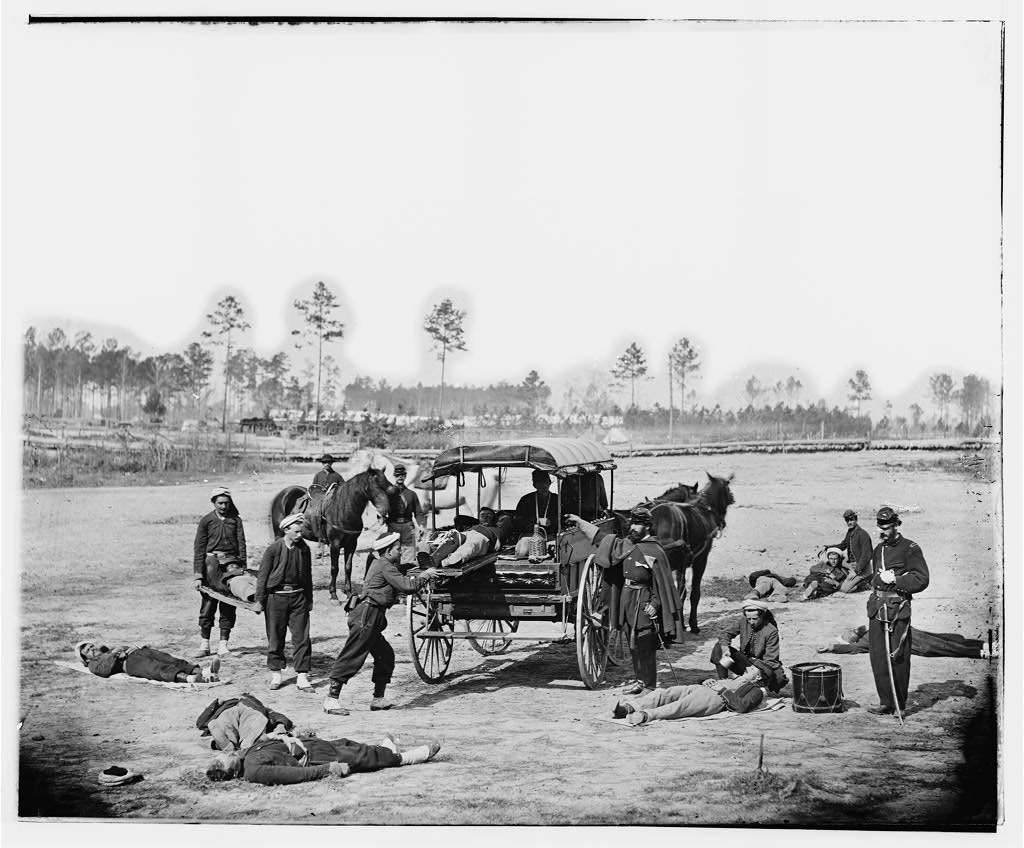

Medicine

Not only were the causes of disease still poorly understood in the 1860s, but by today's standards, army surgeons -- military doctors were all called "surgeons" -- were not skilled at treating disease or at repairing wounds. They operated in conditions we would find primitive, with no antibiotics, no painkillers, and no means of sanitizing surgical tools. Since the germ theory of disease (that disease and infection are caused by microorganisms) hadn't yet been developed and accepted, doctors wouldn't have sterilized their tools in any case.

Of all the wounds soldiers received to their arms and legs, about one in six could not be repaired and resulted in amputation. Amputation could lead to gangrene, in which the flesh rots from lack of blood flow, or to various kinds of infections. Despite these dangers, three-fourths of amputees survived. Given the constraints of the time, army surgeons did well to save as many lives as they did.

1. Wikipedia has a more complete list of U.S. wars and casualties.

2. Data drawn from various sources. Wikipedia probably has the best overview of various casualty estimates.