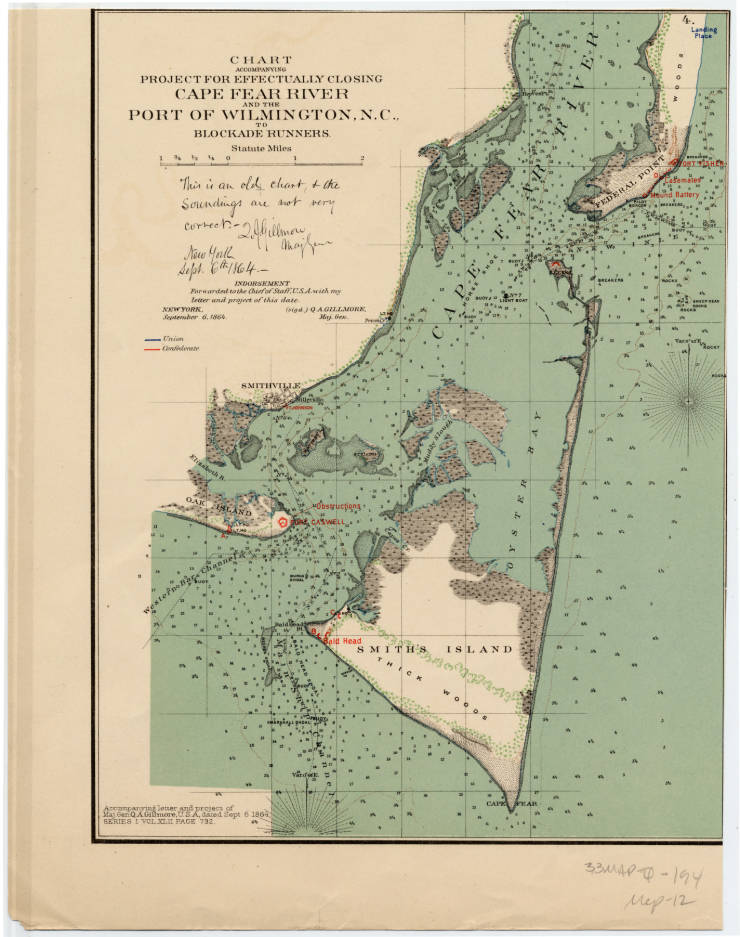

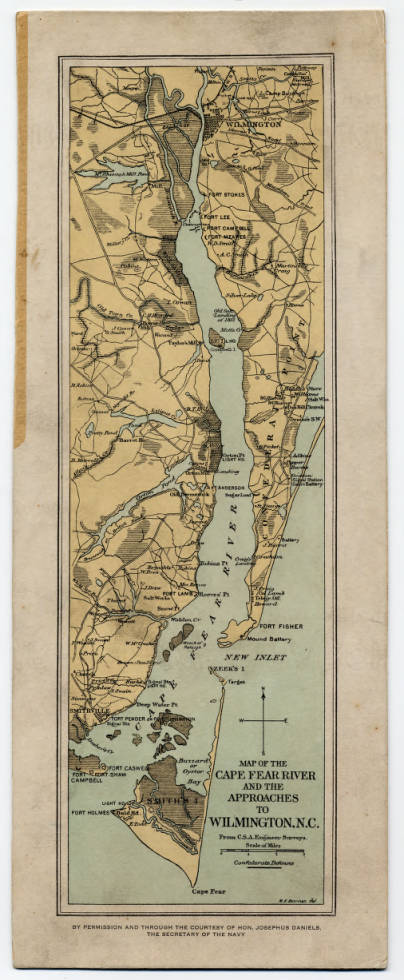

The U.S. Navy had blockaded nearly the entire Confederate coastline as early as 1862, but the port of Wilmington, North Carolina, remained open until January 1865 . The barrier islands and shoals around the mouth of the Cape Fear River made the inlets too difficult for the Union blockaders to guard effectively. Two separate entrances to the Cape Fear -- Western Bar Inlet and New Inlet -- are separated by Smith's Island and the Frying Pan Shoals, which were too shallow for blockade ships to cross. The Confederate guns at Fort Fisher, meanwhile, helped keep Union ships at bay.

Private ships, supported by the Confederate government, continued to squeeze through the port to carry goods such as cotton to European markets or to the British-controlled islands of Bermuda and the Bahamas, and to bring back necessities for troops (and often luxuries as well). As these "blockade runners" steamed south out of Wilmington on the Cape Fear, lookouts and signal stations told them which of the two inlets was more lightly guarded. Since running the blockade was dangerous and goods were scarce as the war went on, blockade runners often made a great deal of money from the goods they brought back. Food and clothing made their way from Wilmington north to Confederate troops in Virginia via the Wilmington and Weldon Railroad, which became known as the "Lifeline of the Confederacy."

In her memoir, Belle Boyd in Camp and Prison (1865), Boyd describes her adventures as a spy and her involvement in the conflict, including her experience aboard the Greyhound, a Confederate blockade runner, when it was captured by Union ships in May of 1864. Although more than 100 ships were captured or destroyed trying to run the blockade, about three-fourths of all blockade runners made it through. The port of Wilmington remained open until Fort Fisher was captured by Union troops in January 1865.

On the 8th of May I bade farewell to many friends in Wilmington and stepped on board the Greyhound. It was, as may well be imagined, an anxious moment. I knew that the venture was a desperate one; but I felt sustained by the greatness of my cause; for I had borne a part, however insignificant, in one of the greatest dramas ever yet enacted upon the stage of the world; moreover, I relied upon my own resources, and I looked to Fortune, who is so often the handmaid of a daring enterprise.

At the mouth of the river we dropped anchor, and decided to wait until the already waning moon should entirely disappear.

At the mouth of the river we dropped anchor, and decided to wait until the already waning moon should entirely disappear.

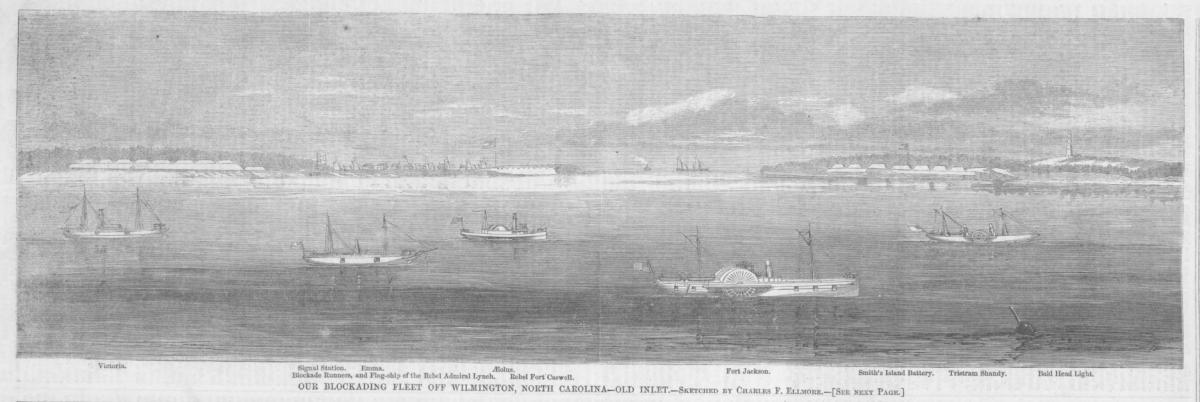

Outside the bar, and at the distance of about six miles, lay the Federal fleet, most of them at anchor; but some of their lighter vessels were cruising quietly in different directions. Not one, however, showed any disposition to tempt the guns of the fort over which the Confederate flag was flying.

There were on board the Greyhound two passengers, or rather adventurers, besides myself -- Mr. Newell and Mr. Pollard, the latter the editor of the "Richmond Examiner." We laughed and joked, as people will laugh and joke in the face of imminent danger, and even in the jaws of death.

Gentle reader, before you accuse us of levity, or of a reckless spirit of fatalism, reflect how, in the prison of La Force, when the reign of terrorThe Reign of Terror (1793-94) was a period during the French Revolution when radicals gained power and executed between 20,000 and 40,000 "enemies of the revolution." The guillotine, which Boyd mentions, was a mechanical means of quickly decapitating someone, and was the preferred means of execution during the Revolution. was at its height, the doomed victims of the guillotine acted charades, played games of forfeits, and circulated their bon mots and jeux d'esprit within a few hours of a violent death. Remember also that the lovely Queen of ScotsMary I of Scotland, known as Mary, Queen of Scots, ruled Scotland from 1542 to 1567. Many English Catholics considered her to be the rightful ruler of England, rather than the Protestant Queen Elizabeth I. Elizabeth had Mary executed for plotting against her. and the unfortunate Anne BoleynAnne Boleyn was the second wife of Henry VIII of England and mother of Elizabeth I. Henry had Anne executed for treason three years after their marriage. met their fate with a smile, and greeted the scaffold with a jest.

About ten o'clock orders were given to get under way. The next minute every light was extinguished, the anchor was weighed, steam was got up rapidly and silently, and we glided off just as "the trailing garments of the night" spread their last folds over the ocean!

The decks were piled with bales of cotton, upon which our look-out men were stationed, straining their eyes to pierce the darkness and give timely notice of the approach of an enemy.

I freely confess that our jocose temperament had now yielded to a far more serious state of feeling. No more pleasantries were exchanged, but many earnest prayers were breathed. No one thought of sleep. Few words were spoken. It was a night never to be forgotten -- a night of silent, almost breathless, anxiety. It seemed to us as if day would never break; but it came at last, and, to our unspeakable joy, not a sail was in sight. We were moving unmolested and alone upon a tranquil sea, and we indulged in the fond hope that we had eluded our eager foes.

Steaming on, we ran close by the wreck of the Confederate iron-clad Raleigh, which had so lately driven the Federal blockading squadron out to sea, but which now lay on a shoal, an utter wreck, parted amidships, destroyed, not by the Federals, but by a visitation of Providence. The CSS Raleigh was not damaged by battle, but instead essentially collapsed under its own weight when the tide went out after it ran aground on a sandbar.

At this point we three passengers began to experience those sensations which, although invariably an object of derision to persons who are exempt from them, are, for the time being, as grievous to the sufferer as any in the whole catalogue of pains and aches to which flesh is heir. Reader, may it never be your lot, as it then was mine, to find sea-sickness overcome by the stronger emotion inspired by the sight of a hostile vessel bearing rapidly down with the purpose of depriving you of your freedom.

It was just noon, when a thick haze which had lain upon the water lifted, and at that moment we heard a startled cry of "Sail ho!" from the look-out man at the mast-head. These ominous words were the signal for a general rush aft. Extra steam was got up in an incredibly short space of time, and sail was set with the view both of increasing our speed and of steadying our vessel as she dashed through the water.

Alas! it was soon evident that our exertions were useless, for every minute visibly lessened the distance between us and our pursuer; her masts rose higher and higher, her hull loomed larger and larger, and I was told plainly that, unless some unforeseen accident should favour us, such as a temporary derangement of the Federal steamer's steering apparatus, or a breaking of some important portion of her machinery, we might look to New York instead of Bermuda as our destination.

My feelings at this intelligence must be imagined: I can describe them but inadequately. "Unless," I thought, "Providence interposes directly in our behalf, we shall be overhauled and captured; and then what follows? I shall suffer a third rigorous imprisonment." Moreover, I was the bearer of despatches from my Government to authorities in Europe; and I knew that this service, honourable and necessary as it was, the Federals regarded in the light of a heinous crime, and that, in all probability, I should be subjected to every kind of indignity.

The chase continued, and the cruiser still gained upon us. For minutes, which to me seemed hours, did I strain my eyes towards our pursuer and watch anxiously for the flash of the gull that would soon send a shot or shell after us, or, for all I could tell, into us. How long I remained watching I know not, but the iron messenger of death came at last. A thin white curl of smoke rose high in the air as the enemy luffed up and presented her formidable broadside. Almost simultaneously with the hissing sound of the shell, as it buried itself in the sea within a few yards of us, came the smothered report of its explosion under water.

The enemy's shots now followed each other in rapid succession: some fell very close, while others, less skilfully aimed, were wide of the mark, and burst high in the air over our heads. During this time bale after bale of cotton had been rolled overboard by our crew, the epitaph of each as it disappeared beneath the waves being "By --! there's another they shall not get."

Our captain paced nervously to and fro, now watching the compass, now gazing fixedly at the approaching enemy, now shouting "More steam! more steam! give her more steam!" At last he turned suddenly round to me, and exclaimed in passionate accents --

"Miss Belle, I declare to you that, but for your presence on board, I would burn her to the water's edge rather than those infernal scoundrels should reap the benefit of a single bale of our cargo."

To this I replied, "Captain 'Henry,' act without reference to me -- do what you think your duty. For my part, sir, I concur with you: burn her by all means -- I am not afraid. I have made up any mind, and am indifferent to my fate, if only the Federals do not get the vessel."

To this Captain "Henry" made no reply, but turned abruptly away and walked aft, where his officers were standing in a group. With them he held a hurried consultation, and then, coming to where I was seated, exclaimed --

"It is too late to burn her now. The Yankee is almost on board of us. We must surrender!"

During all this time the enemy's fire never ceased. Round shot and shell were ploughing up the water about us. They flew before, behind, and above -- everywhere but into us; and, although I knew that the first of those heavy missiles which should strike must be fatal to many, perhaps to all, yet so angry did I feel that I could have forfeited my own life if, by so doing, I could have baulked the Federals of their prey.

At this moment we were not more than half a mile from our tormentor; for we had huffed up in the wind, and stopped our engine. Suddenly, with a deep humming sound, came a hundred-pound bolt. This shot was fired from their long gun amidships, and passed just over my head, between myself and the captain, who was standing on the bridge a little above me.

"By Jove! don't they intend to give us quarter, or show us some mercy at any rate?" cried Captain "Henry." "I have surrendered."

And now from the Yankee came a stentorian hail. "Steamer ahoy! haul down that flag, or eve will pour a broadside into you!"

Captain "Henry" then ordered the man at the wheel to lower the colours; but he replied, with true British pluck, that "he had sailed many times under that flag, but had never yet seen it hauled down; and," added he, "I cannot do it now." We were sailing under British colours, and the man at the helm was an Englishman.

All this time repeated hails of "Haul down that flag, or we will sink you!" greeted us, until, at last, some one, I know not who, seeing how hopeless it must be to brave them longer, took it upon himself to execute Captain "Henry's" order, and lowered the English ensign.

Primary Source Citation:

Boyd, Belle. Belle Boyd in Camp and Prison With an Introduction by a Friend of the South. In Two Volumes. Vol II. London.: Saunders, Otley, and Co., 1865.

Published online by Documenting the American South. University Library, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. https://docsouth.unc.edu/fpn/boyd2/menu.html

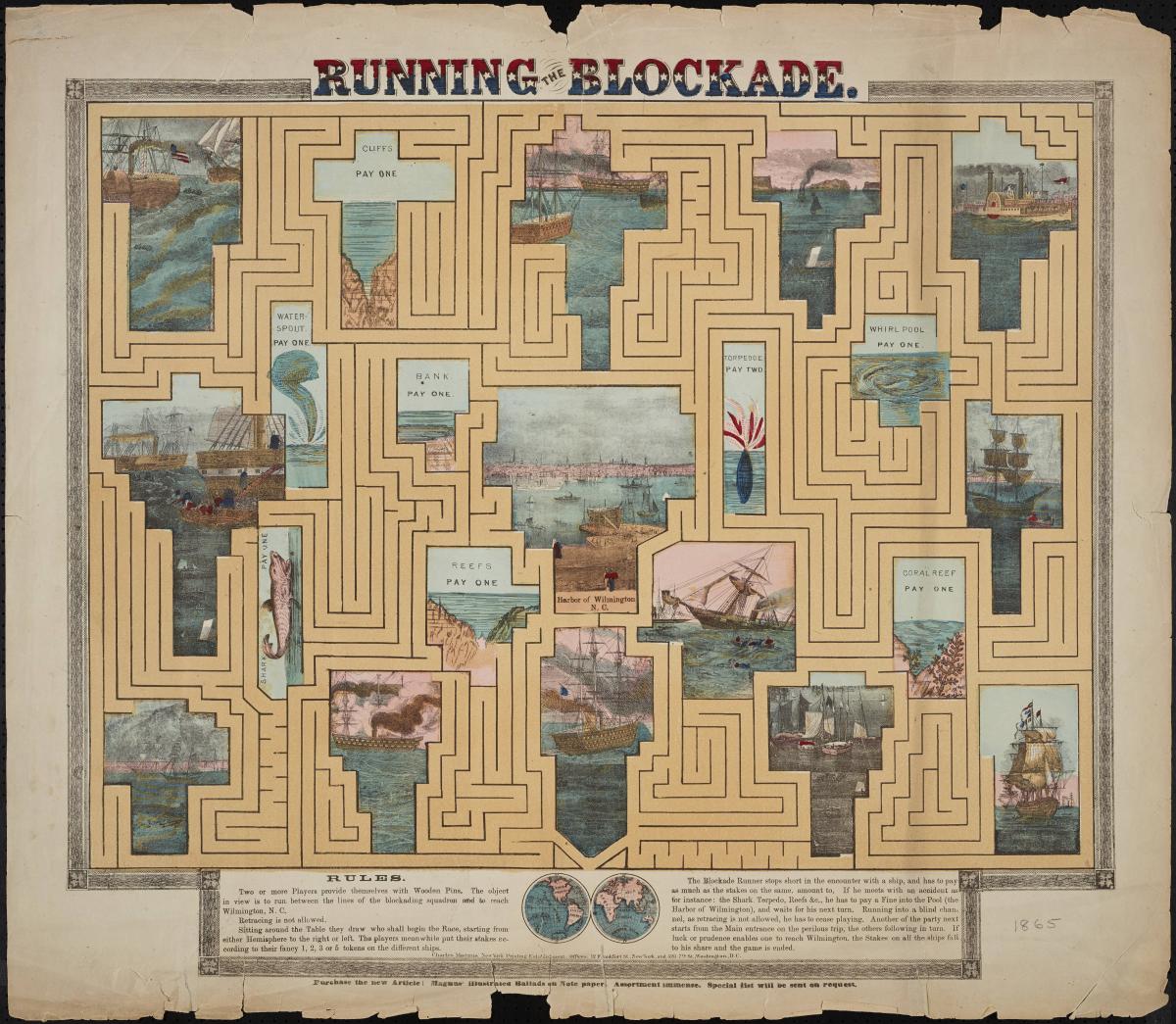

Running the Blockade Board Game

Running the Blockade Board Game Sketch depicting Union ships waiting off the mouth of the Cape Fear River

Sketch depicting Union ships waiting off the mouth of the Cape Fear River