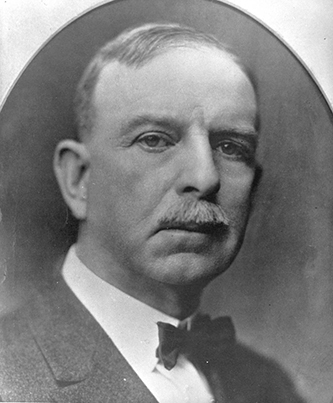

6 Aug. 1861–13 Mar. 1933

Eugene Cunningham Branson, educator, author, and editor, was born in Morehead City, oldest of the seven children of the Reverend Levi and Edith Cunningham Branson. The Reverend Mr. Branson, an ordained Methodist minister, occupied various pulpits and traveled extensively in the United States and abroad; he established a book store and publishing firm in Raleigh, which he operated for many years.

Little is known of Branson's early education; his schooling was probably conducted in his home or in a small private school. He entered Trinity College (now Duke University) in 1877 and completed an M.A. degree in 1879. He also attended George Peabody Normal College in Nashville, Tenn., where he received another M.A. degree in 1883. Following graduation from Peabody, Branson worked fourteen years in secondary education as principal of a high school in Raleigh and as superintendent of public schools in Wilson, N.C., and Athens, Ga. (the first public school system in Georgia). Before leaving North Carolina he became the youngest member of the Watauga Club, an organization of leading cultural and political men in Raleigh who studied the state's social and economic resources and offered suggestions for their utilization. While in Georgia, Branson wrote three publications for public school use: Methods of Teaching Arithmetic (1896), Methods of Reading and Spelling (1896), and a chapter in Page's Theory and Practice of Teaching entitled "Fitness to Teach" (1899).

Branson left secondary education for higher education in 1897, when he accepted an appointment as professor of pedagogy at Georgia Normal and Industrial School in Milledgeville. He remained at the Milledgeville school until 1900, when he became the president of State Normal School of Georgia in Athens. While serving the Athens school he organized the Georgia Club in 1902, to familiarize future teachers of Georgia with their state, and established the state's first department of rural economics and sociology in 1912. He also found time to write Branson's Common School Speller published in 1903, and to edit an eight-page magazine called Home and Farmstead in 1912, which printed studies of rural conditions in Georgia made by the rural economics and sociology department.

Branson's work in Georgia prepared him for greater achievement in his native state, where he returned in 1914 to head The University of North Carolina's new department of rural social economics. For almost nineteen years, he ably administered the department's four-fold work: (1) offering formal textbook courses, (2) establishing a seminar library, (3) conducting regional studies on county government, and (4) answering calls for information and assistance from citizens of the state. The success of his work in North Carolina led to the establishment of similar departments of rural social economics in Virginia, Tennessee, and South Carolina.

The courses Branson taught were unique as well as popular. While using textbooks as a background for interpretation, he explored the problems of rural life in North Carolina and suggested constructive policies to meet them. The courses were strictly elective and open only to juniors, seniors, and graduates; Branson spoke the language the young men of the twentieth century were eager to hear, however, and his courses were taken by over four thousand students. Three of his students attained prominence in the field of rural social economics: Wilson Gee in Virginia, J. A. Dickey in Arkansas, and S. H. Hobbs, Jr., in North Carolina. In addition to teaching at The University of North Carolina, Branson held summer school seminars in California, Utah, Texas, Alabama, Tennessee, and Louisiana.

The rural social economics seminar library established by Branson was one of the first of its kind in the nation. More important than the books purchased by the library's meager annual fund were the newspaper clippings, learned journal articles, monographs, bulletins, and reports assembled daily by the department staff. This holding of material dealing with country life in the state, the nation, and many foreign countries became a clearinghouse of information for readers, scholars, and leaders of the state in matters concerning North Carolina.

With the aim of improving local government throughout North Carolina, Branson supervised field workers in the study of county government in sixty-one rural counties of the state. This work earned him an appointment to Governor Angus W. McLean's advisory commission on county government and influenced the introduction of various reform bills in the 1927 state legislature: the county fiscal control bill, the county finance act, the county management system act, and a tax-collecting act.

Perhaps the most far-reaching work of the rural social economics department was the answering of calls for information and assistance—two thousand a year, on the average—from the citizens of the state. It was not unusual for such requests to require days of research.

In addition to departmental duties, Branson worked as editor from 1914 until 1922 of the weekly university News Letter, a one-page, widely circulated paper (18,000 subscribers and 310 newspapers), discussing specific facts about county affairs as well as general social and economic problems of North Carolina. He also helped organize in 1914 the North Carolina Club, a group of faculty members, students, and townspeople interested in the study of problems facing the state. Papers delivered by members at club meetings were complied into yearbooks, which were made available to interested citizens of North Carolina. Branson was awarded a Litt.D. degree by the University of Georgia (Athens) in 1919 and the same year was appointed a Kenan professor at The University of North Carolina. He was given a leave of absence in 1923 to study agricultural conditions in various European countries, especially Denmark; as a result, he wrote a widely acclaimed book entitled Farm Life Abroad (1924). He delivered many addresses and wrote extensively on the subjects of farm tenancy, illiteracy, farm credit, and crop diversification; and he championed movements for farm land reclamation, better port facilities, and good roads for North Carolina.

Although a Presbyterian and a Democrat, Branson was respected by men of many religious and political backgrounds. His faith in humanity and infinite patience with his fellowmen were characteristics most admired by those who knew him. His marriage on 27 Sept. 1889 to Lottie Lanier of West Point, Ga., produced four children: Frank Lanier, Edith Lanier (Mrs. Young B. Smith), Phil Lanier, and Elizabeth Lanier. Branson died in Duke Hospital and was buried in Old Chapel Hill Cemetery.