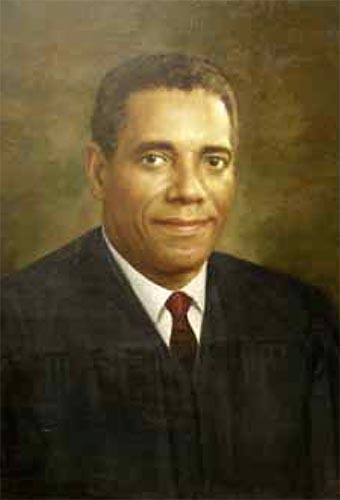

Clifton Earl “Cliff” Johnson was a pioneer African American jurist. He was born in 1941 in Williamston, Marin County, North Carolina. He was the fourth of nine children of Charlie Johnson and Willie Ann McNair Johnson and grew up in a wooden frame house. Charlie Johnson was the first African American police officer in Williamston. Johnson attended E. J. Hayes High School, where he played football, basketball, and ran track. He worked hardscrabble jobs as a youngster to make money for school including as a trash collector. Johnson’s strong upbringing and humble origins inspired his decisions as a jurist. And they established the tenor of his career dedicated to service. In spite of his many professional successes, he never abandoned his roots.

Johnson was a strong student in high school. He won an academic scholarship to attend North Carolina College (NCC), now North Carolina Central University. In 1961, he entered NCC as part of a special program that allowed students to earn their undergraduate and law degrees in six years. As an undergraduate, he worked for the student newspaper, the Campus Echo. And during that time, he married his childhood sweetheart, Brenda Joyce Wilson. He finished his undergraduate education in 1964 and then entered the NCC Law School.

He spent the summers of 1965 and 1966 as a law clerk for the American Civil Liberties Union in New York City. He earned his Juris doctorate in 1967 and went into private practice in Durham. After being in private practice for a short time, Johnson joined Durham's first Black law firm, Pearson, Malone, Johnson, and DeJarmon. Johnson aspired to become a judge and wanted to work full time as a prosecutor to prepare himself. Unfortunately, there were no opportunities to be a prosecutor in Durham at that time.

Later that year, Johnson began prosecuting recorders court cases in Durham on a per-day basis. In 1969, a full-time assistant solicitor position opened up in Mecklenburg County. Johnson was hired, becoming the first African American to prosecute cases in North Carolina since the 19th Century. He worked as a prosecutor for a little more than a year before Governor Bob Scott appointed him district court judge of the 26th judicial district in 1969. Johnson was North Carolina’s first African American district court judge. In 1974, N.C. Supreme Court Chief Justice William H. Bobbit appointed Johnson chief district court judge in Mecklenburg. He was the first African American chief district court judge in the county and in the state.

As chief district court judge, Johnson was responsible for the seven other district court judges and twenty-one magistrates. He distinguished himself on the district court bench by clearing a chronic backlog of court cases and helping to create Mecklenburg’s Pretrial Release Program (PTR). The PTR aimed to reduce the population of the county’s crowded jails and to help low-risk offenders who could not make bond. Under the program, people who qualified were released from jail without having to pay bond. Johnson also worked to improve diversity in the court system. As Chief District Court judge, he hired the state’s first African American court reporter.

In 1977, Governor James B. “Jim” Hunt, Jr. appointed Johnson resident Superior Court judge for Mecklenburg County. Johnson was also the first African American in the state to hold that position. He achieved another first in 1982 when Governor Hunt appointed him to the North Carolina Court of Appeals. Hunt stated, “On the bench, he was as strong, as careful, as insistent on things being done right as any person I’ve ever seen.” On the Court of Appeals Johnson became the first African American Chair of the Judicial Standards Committee. And he hired the first black executive assistant in the Court of Appeals.

Johnson retired from the Appellate Court in 1996 with the rank of Senior Associate Judge. In retirement, he often worked as a fill-in Superior Court Judge. Even in retirement he led by example and remained true to his humble upbringing and ethic of service to others. When the state temporarily stopped funding fill-in Superior Court judges, Johnson agreed to hold court wherever he was needed. He worked without compensation because he believed the people of the state had been good to him.

Johnson died of an apparent heart attack on June 25, 2009, while attending a judge’s conference in Asheville, North Carolina. In 2012, Mecklenburg County renamed a government building in his honor. Judge Johnson and his wife Brenda had four children: Yulonda Johnson Ervin, Clifton Johnson II, Khiva Johnson, and Understanding Knowledge Allah Ali.