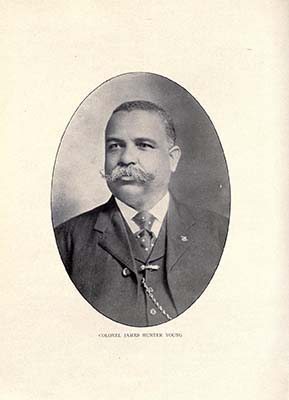

October 26, 1858–April 11, 1921

James Hunter Young, politician, editor, businessman, and racial spokesman, was born near Henderson. His mother was enslaved by Captain Demetrius Ellis Young, and his father was "a prominent white man in Vance County" who assumed responsibility for his education and was instrumental in securing his first political appointment. Young attended common school in Henderson and in 1874 entered Shaw University in Raleigh, an institution to which he remained devoted throughout his life. In January 1877 he left Shaw to take a job in the office of Colonel J. J. Young, the collector of internal revenue for the Fourth District of North Carolina, a decision that marked the beginning of his career in Republican politics.

Young's industry and efficiency attracted the attention of state Republican leaders and resulted in his rapid advancement within both party circles and the Internal Revenue Service. By 1882 he had become chief clerk and cashier in the Fourth District revenue office. First chosen a delegate to the Republican state convention in 1880, Young was prominent in North Carolina party councils for more than three decades. He was an alternate delegate and delegate-at-large to the Republican National Convention in 1884 and 1892, respectively.

When Grover Cleveland entered the White House in 1885, Young was replaced in the revenue service by a white Democrat. Even though Democrats controlled federal patronage, the young black politician had influential Republican friends in local government. Through them he was appointed, in December 1886, chief clerk in the office of the Register of Deeds in Wake County, a position that he held for more than two years. By the time the Republicans returned to power in Washington in 1889, Young had emerged as one of the most influential black Republicans in North Carolina. During the next decade he "was easily the outstanding Negro in state influence."

In 1889, largely through the influence of his friend and political associate, Henry Plummer Cheatham, North Carolina's black congressman, Young was appointed a special inspector of customs. A year later President Benjamin Harrison selected him to be collector of the port of Wilmington, one of the most prestigious and lucrative patronage positions in the state. The appointment triggered a prolonged and acrimonious controversy, and despite the efforts of Cheatham and other North Carolina Republicans, the state's Democratic leadership was able to prevent his confirmation by the Senate. With the beginning of Cleveland's second administration in 1893, Young was relieved of his post as a special customs inspector and once again "returned to private life."

Early in the 1890s party politics in North Carolina underwent dramatic changes in large part because of the emergence of the Populists. An ambitious and skillful politician, Young took maximum advantage of these developments to advance his own political career as well as the welfare of black citizens in general. In June 1893 he purchased the Gazette, a weekly newspaper published in Raleigh. During the five years in which he edited the Gazette, the paper was not only recognized as the principal mouthpiece of black Republicanism in the state, but its columns also reflected Young's personal interest in various programs of racial uplift, especially those concerning education, moral development, and economic self-help. An articulate, forceful individual whose talents won for him the respect of white as well as black people, Young entered upon the most significant phase of his political career in 1893–94, when negotiations between Republicans and Populists sought to effect an arrangement known in North Carolina as Fusion. A staunch advocate of Republican-Populist cooperation, Young labored with considerable success in winning the support of those black Republicans who were wary of such an alliance. Indeed, he was one of the principal architects of the Fusionist strategy by which Populists and Republicans wrested control of state politics from the Democrats in the 1890s.

In 1894 Young was elected to the state legislature from Wake County on a Fusion ticket, and two years later he was reelected. Notwithstanding the carping criticism leveled at him by Josephus Daniels's News and Observer, his performance as a legislator provided abundant evidence of his ability, energy, and political astuteness. A member of the half-dozen important committees in the state House of Representatives, Young displayed particular concern for measures relating to education, penal reform, and charitable institutions, such as the school for the deaf, dumb, and blind. Nothing, however, provoked more hostility from Democratic quarters than his success in obtaining revisions in the Raleigh city charter that allowed black people greater opportunities for participation in municipal affairs.

In the election of 1896 Young played a key role in the campaign of Daniel L. Russell, a Republican, who ran for governor on the Fusion ticket. During the four years following the triumph of the Fusionists in 1896, Young reached the apex of his political power and prestige. He enjoyed the confidence of both the governor and Republican senator Jeter C. Pritchard. Governor Russell appointed him chief fertilizer inspector in the state and a member of the board of directors of the deaf, dumb, and blind institutions whose interests he had consistently championed earlier as a legislator.

The Democratic press, already outraged by the selection of a black man to serve as a director of the state's principal charitable institution, unleashed a barrage of racist rhetoric against Young when, on the outbreak of the Spanish-American War, Governor Russell appointed him colonel of a regiment of black volunteers designated as the Third North Carolina Infantry. Although the regiment never saw combat and remained in the United States, its existence was a source of considerable pride among black North Carolinians. Some of the white Democrats who had been most severe in their denunciation of Colonel Young in 1898 later admitted that he and his men "made much better soldiers than anybody expected."

By the time the black regiment was mustered out early in 1899, the Democrats had mounted an effective offensive against the Fusionists. Throughout their white supremacy campaign in the fall of 1898, they had equated Fusion rule with "negro rule"—a theme that proved useful not only in turning the Republicans and Populists out of office but also in disfranchising black voters. The Democratic legislature of 1899, intent on obliterating all reminders of "negro rule," passed a resolution directing that the name of James H. Young be removed from the cornerstone of the new school for the deaf, dumb, and blind, an institution that he had championed both as a legislator and as a member of its board of directors.

Although the return of the Democrats to power meant that Young was no longer a significant force in North Carolina politics, the Republican administrations in Washington did not ignore his services to the party. In 1899 President William McKinley appointed him deputy revenue collector for the Raleigh district, a position to which he was reappointed by both Theodore Roosevelt and William Howard Taft. In 1913, early in the Democratic administration of Woodrow Wilson, Young's career in the federal service, which altogether totaled more than a quarter of a century, came to an end. Observers interpreted his removal as deputy revenue collector as an event of major significance, because by 1913 he was the sole black man occupying a federal position of any consequence in North Carolina.

After his dismissal Young retired from politics and devoted himself to a variety of business, religious, civic, and fraternal enterprises with which he had been identified for many years. From a suite of offices in the Masonic Temple in Raleigh he conducted a profitable business in insurance and real estate. In addition, he was president of the Raleigh Undertaking Company and a director of the Mallette Drug Company. An example of sobriety and "clean living," he continued to maintain an interest in the affairs of the Baptist denomination, which he had served in various capacities including those of Sunday school superintendent in Raleigh's First Baptist Church and president of the Baptist State Sunday School Convention. Widely known in fraternal circles, he held important posts in the Odd Fellows, Masons, Knights of Pythias, and the Household of Ruth.

Throughout the decade following his retirement from politics, Young functioned as an elder statesman among black North Carolinians. A social pacifist who abhorred violence, he sought to maintain harmony between the races. During World War I his services as a public speaker were much in demand at patriotic rallies, and Selective Service officials often called upon him for advice in regard to the drafting of black men. In the racially turbulent era immediately after the war his principal message was a call for "moderation" on the part of both white and black people—a position that caused some black people to charge that he was "recreant to the race."

Young was married three times. In 1881 he married Bettie Ellison, the daughter of Stewart Ellison, a prominent black politician and businessman in Raleigh. His second wife was a widow, Mrs. Mary Christmas, and his third was Lula Evans of Raleigh who he married in July 1913. He was the father of two daughters, Maude and Martha. At his funeral on April 13 1921, "the high and low, irrespective of race, gathered in tremendous throng" in the First Baptist Church to pay tribute to a man who was credited with being in large measure responsible for "the friendly relations obtaining between the races in North Carolina."