Hatting, or hat making, was a significant craft in North Carolina from the mid-eighteenth century well into the nineteenth. In a letter dated 4 Jan. 1754, Governor Arthur Dobbs informed the Board of Trade that a few hats were being made in the colony. Governor William Tryon in 1767 reported that the colony had five or six hatters but "none of them of any note." Many of North Carolina's hatters were among the settlers who poured through the Shenandoah Valley into the colony beginning in the mid-1700s. These skilled craftsmen from hat-making centers such as Philadelphia, Nantucket, and Danbury, Conn., usually engaged simultaneously in farming, milling, or tanning, with hat making as a profitable and even prestigious sideline. In the state's social hierarchy, hatters and other artisans were just below the level of the gentry.

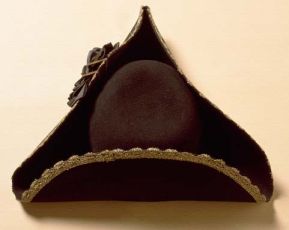

Early styles, primarily for men, included the felt threecornered hat, the broad-brimmed Quaker hat, and various high hats. Those who wore high hats paid an annual state tax of four dollars for the privilege. Better quality hats were made of fur, with beaver pelts being most desirable. A high-quality handmade hat could cost more than any other article of clothing, the equivalent of $50 in today's currency. To keep costs down, hatters sometimes substituted raccoon, otter, and muskrat for beaver skins. An inferior grade of felt was made of wool and vegetable fibers.

North Carolina's hat-making industry was most vibrant in the Piedmont and Mountains. Among the few hatters known to operate in the eastern region were Constant Devotion and Samuel Snowden in Edgecombe County. They produced beaver or castor hats, competing with less expensive felt hats imported from England. Because imports were not readily available in interior regions, those with the skills and tools to make hats had a ready market.

Around the mid-eighteenth century, the Beard family, Quakers from the North, began making hats in Guilford County. In 1795 20-year-old David Beard inherited the trade and tools from his father William and thereafter built a profitable business. He also held two patents for blocking and cutting machinery. Salem Village in Forsyth County also boasted several hatmakers.

In Transylvania County in western North Carolina, hat making was a lively industry during the decades leading up to the Civil War. Jimmie Neill's Hattery Shop, located about two miles north of Brevard, was among several places where headgear was fashioned from the pelts of local wild animals. Another Transylvania hatter, Billy Wilson, known far and wide as "Hatter Billy," made hats from his sheep's wool. Wilson sheared the sheep, his wife carded and spun the wool, and then he dyed it using walnut hulls.

The introduction of mass-produced hats during the industrial age of the late nineteenth century led to a decline in the number of hatters in the state. By 1884 only four counties listed a hatter among their tradesmen, as hatters, like other artisans, had shifted from production to retailing.