1671–3 Apr. 1763

Morgan Bryan, founder of a pioneer clan on the Forks of the Yadkin, was born in Denmark and came to America from Ireland in 1695 or somewhat later.

By the time of his 1719 marriage to Martha Strode, Bryan owned land in Birmingham Township, Chester County, Pa. Shortly after his marriage, he moved farther west in the county and may then have begun trading activities with the Indians who came to the Conestoga River to exchange furs for goods.

For a time, Bryan lived in what is now Lancaster County, Pa., where he was associated with his younger brother William and the Linville brothers in the Conestoga trade. In the three years prior to 1729, he lived on a 137-acre farm in Marlborough Township, Chester County, among prosperous Quaker farmers.

Although Bryan went to Pennsylvania from northern Ireland under Quaker auspices and was closely associated with prominent Friends during his residence in Pennsylvania and for many years thereafter, he apparently held membership in the society for only a brief period. His only recorded formal affiliation is his listing on the rolls of the New Garden Quaker Meeting of Chester County in 1719.

Bryan's reputed family background suggests conversion to Presbyterianism, a deduction sustained by the fact that his younger brother William—who came to Pennsylvania from northern Ireland in 1718—helped organize the Donegal Presbyterian Church in Lancaster County in 1721–22 and by the fact that Morgan himself invited a Presbyterian minister to hold services at his frontier home in the Shenandoah Valley many years later.

Contact with Indians and white traders from the western hinterlands doubtless stimulated Bryan's interest in the Shenandoah country. With his Quaker friend Alexander Ross he explored the northern gateway to this beautiful valley in 1729. The following year, the pair presented a proposal to the council of Virginia and the governor for a large-scale colonization project. They were granted a one-hundred-thousand-acre tract in the vicinity of the present Winchester. It was stipulated that land patents would be granted within two years to one hundred families and that Bryan and Ross would divide the land in any manner agreeable to the settlers.

Virginia's colonial government had long attempted to discourage western settlement for fear of antagonizing the Indians, but the policy had proved unenforceable; the council apparently decided it wiser to populate the area in an organized way with hard-working Quaker farmers than to try to keep squatters and renegades out. Once the farmers were established, undesirables could be dealt with far more effectively through their local governments than through attempts at control from Williamsburg. Moreover, the Bryan–Ross project would test the validity of Lord Fairfax's claim to the Northern Neck region, which the council disputed.

The settlement venture was eminently successful. Through the 1730s and 1740s, Bryan lived at two or three locations in the region, as the needs of his growing family and his land-trading activities dictated. Real estate speculation seems to have been an important source of his income. As a result, he built less permanently than some of his contemporaries, whose farmsteads have survived to this day. Extending his activities progressively farther south into the valley, Bryan became a man of considerable means and influence. The records of Virginia's original western counties contain many references to his services as justice, surveyor, juror, and road overseer, as well as to his real estate transactions.

As Bryan's older children began forming their own families, he searched for sufficient unclaimed land to support the future needs of the growing clan. The Shenandoah Valley was rapidly filling with people, and his own success as a promoter contributed to the need to look elsewhere. His sons scouted far to the south, and at length Bryan decided to lead his family to Lord Granville's land south of the Virginia border. Thus, in 1747, he began winding up his business affairs in the valley; in that year he gave power of attorney to a business associate to dispose of his remaining property and collect monies owed him.

Morgan and Martha Bryan, together with all their children and grandchildren, set out on the long journey south in the fall of 1748. The eldest son, Joseph, and his young family may have been left behind temporarily to help tie up loose ends. Also left behind was the grave of the Bryans' second child, Mary, who had died in 1743, a year after the death of her young husband, Thomas Curtis. The Curtis's infant daughter, Mary, left in the care of grandmother Bryan, was among the several young children who endured the long trek to Carolina. The Bryan caravan undoubtedly stayed for a time with Morgan's brother William, who, with his sons, had been the first to settle the present site of Roanoke, Va., in 1745. William, from whom William Jennings Bryan traced his descent, died in 1789 at the age of 104.

The Bryan clan reached the Forks of the Yadkin in the spring of 1749. The patriarchal Morgan was then seventy-eight years of age. Within four or five years, he laid claim to fifteen or more choice tracts within the Granville Grant, totaling several thousand acres. Son-in-law William Linville acquired two thousand acres and Joseph, Samuel, and Morgan, Jr., also purchased substantial acreage. Originally in Anson County, all the Bryan property lay within Rowan County when the latter was formed in 1753.

By the time the Moravians arrived from Pennsylvania in 1752 and selected the 155-square-mile tract that was to become Wachovia, the neighboring area to the west was already known as "the Bryan settlements."

Bryan's extensive purchases reflected not only his desire to acquire a legacy for his unmarried sons but also his intention to continue his activities as a land speculator. His many subsequent land transactions confirm this intent, and Rowan County records suggest that several sons followed their father's example. The heart of the Bryan Settlements described an arc across the northern half of the present Davie County. On the east, the arc anchored on the Yadkin with the property of Samuel Bryan, just south of the "shallow ford" where the "great wagon road" between Wachovia and the new county seat of Salisbury crossed the river. Morgan Bryan's Mansion House was located on Deep Creek about four miles north of the shallow ford.

The Bryans were soon joined in the Forks region by the Carters, Hartfords, Davises, Hugheses, Linvilles, Forbeses, Boones, and others, many of whom they had known in Virginia and Pennsylvania. Along with the heads of some of these families, Bryan played an important part in Rowan County's early government. Staunch Quaker Squire Boone, whose numerous sons included Daniel, served as the county's first justice, and Bryan was a member of the first grand jury.

The population of the Forks region grew rapidly during the 1750s as new families arrived in increasing numbers from the northeast. The decade saw the remainder of the Bryan sons marry and strengthen the clan's influence in the area north of Salisbury. William Bryan, the sixth son, married Squire Boone's daughter Mary. Her brothers Daniel and Edward married Bryan sisters Rebecca and Martha, daughters of Morgan's eldest son, Joseph. A few years later, George, another of Squire Boone's sons, married another of Morgan's granddaughters, Nancy Linville, daughter of William and Eleanor Bryan Linville. These marriages marked the beginning of a remarkable bond between the Bryan and Boone families, which was to persist for nearly a century. Succeeding generations saw several more Boone-Bryan marriages, as well as simultaneous migrations to Kentucky and, later, to Missouri.

The aging Morgan and Martha Bryan lived to see their children firmly established in the growing frontier community. They also survived the terrifying Cherokee raids of 1758–61 and saw their sons take part in the military actions that ultimately quelled the depredations and secured the region. Morgan, Jr., was a militia captain and Thomas an ensign. Sons Samuel, John, William, and James also performed militia service during the short but vicious war, during which hundreds of families fled the region and hundreds more were killed. Bryan and his wife did not live, however, to see the profound influence their children and grandchildren exerted upon local affairs during the tumultuous period of the Revolutionary War, nor the prominent role they played in wresting Kentucky from British-led Indians with the founding of Boonesborough and Bryan's Station.

Eight of the Bryan children survived their parents.

Joseph, father-in-law of Daniel and "Neddy" Boone, participated in his brother William's Kentucky land venture during the Revolution but returned to remain in the Bryan Settlements in Rowan County until about 1798. He was a suspected Loyalist; some of his sons served with local Tory militia and others with rebel irregulars. Joseph died in Kentucky in 1804 or 1805.

Eleanor Bryan Linville, whose husband, William, and son John were killed by Indians while hunting in the Blue Ridge Mountains in 1766, did not remarry; she left the Yadkin area with her married children after the Revolution and died in Kentucky in 1792.

Samuel, who served with distinction as a Loyalist colonel during the war, was tried and sentenced to death but exchanged for a rebel officer. In spite of the bitterness that persisted long after the Revolution, Samuel's personal stature was such that he was allowed to retain most of his property in the Bryan Settlements. He continued to live on the Yadkin until his death in 1798. At least one of his Tory sons moved to upstate New York after the war.

Morgan, Jr., who died in Kentucky around 1800, also helped his brother William establish Bryan's Station. Some of his sons may have served in the Revolution as North Carolina Loyalists, although Morgan and one of his sons are credited with rebel militia service in Kentucky.

James, who also helped found Bryan's Station, became a widower in 1770. His six small children were raised by niece Rebecca Boone and her husband, Daniel. James died in Kentucky in 1807; most of his children went to Missouri in 1800 with their uncle Daniel and his party of Boones, Bryans, and other relatives.

John, who is believed to have lost two Tory sons during the Revolution, farmed his land in the Bryan Settlements throughout his life. He died there in the winter of 1799–1800.

William—the intrepid but tragic "Billy" Bryan whom the Moravians admired—declined the king's commission as lieutenant colonel and instead organized and led the establishment of Bryan's Station (1775–79) near the present Lexington, Ky. He was killed there by Indians in May 1780. Only weeks before his death, he lost a son in a similar Shawnee ambush near the station. A few months earlier, he had learned that most of his Kentucky land claims were invalid. William and two of his sons—branded as Tories in Rowan County—were credited with rebel service for having participated in militia actions against Kentucky's Indians.

Thomas, youngest of the children, shared his brothers' interest in Kentucky and is believed to have fitted out one of Daniel Boone's early expeditions. He saw service in the Rowan County militia prior to the Revolution and is thought to have had strong Loyalist sentiments. Thomas inherited his father's Deep Creek property but sold it to his brother William and was living elsewhere in the Settlements at the time of his death in 1777. One of his sons seems to have been killed in the war as a Tory officer. His widow, Sarah Hunt Bryan, later married the Reverend John Gano and moved with him to Kentucky in 1789.

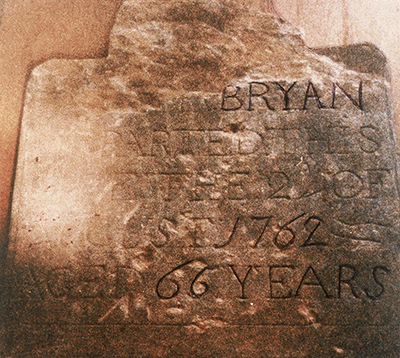

Morgan Bryan, patriarch of the families that helped open Western Carolina and Kentucky to settlement, died on Easter Sunday 1763, at the age of ninety-two. Martha Strode Bryan had died a few months earlier, in August 1762. Both Morgan and his wife are believed to have been buried on their Deep Creek property. Martha Bryan's tombstone was found during the construction of a highway in northeastern Davie County many years ago and is now in the Rowan Museum at Salisbury.