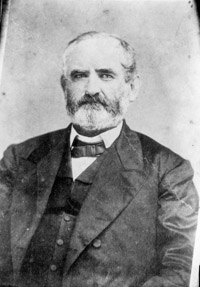

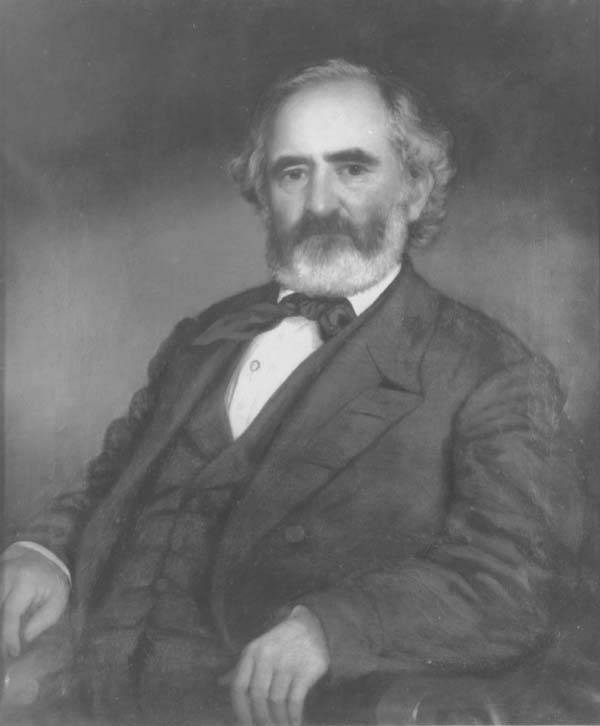

1818–11 July 1874

Tod Robinson Caldwell, lieutenant governor and governor, was born in Morganton, the son of an Irish immigrant who became a prominent Burke County merchant. He obtained the rudiments of reading and writing at a local school and then went to Hillsborough, where he prepared for college by studying under William J. Bingham. Caldwell entered The University of North Carolina and was graduated with honors in 1840. While in college, in addition to pursuing the regular curriculum, he read law under President David L. Swain. In 1841 he began practicing law in Burke County, and in the same year he won the first of many elections to public office, that of county prosecuting attorney. He never lost an election. His success as a criminal lawyer brought him a measure of fame in the mountain counties, which contributed to his election at the age of twenty-four to the state House of Commons. "A Henry Clay Whig of the most enthusiastic stripe," Caldwell served several terms in the house and in the senate, to which he was first elected in 1850.

During the sectional crisis of the 1850s, Caldwell, like most North Carolina Whigs, resisted the movement to take the state out of the Union. But unlike most of his fellow Whigs, he retained his allegiance to the Union after secession, taking no part in the war, although his only son to survive infancy fought in Lee's army—and died at Gettysburg. After the war, Caldwell, along with the many Union Whigs who were anxious for an early restoration of the state to the Union, served in the constitutional convention of 1865 called under President Johnson's plan of Reconstruction. When Johnson's lenient policies toward Confederates failed to result in reunion and, in fact, alienated the Republican majority in Congress, Caldwell disassociated himself from the president and in 1867 served as one of the founders of the Republican party in North Carolina. Although no friend of rights for Black Americans when he joined the Republican party, he warmed to the idea of supporting its platform of Black suffrage and rights. Before reentering politics, he served in 1865–66 as president of the state-owned Western North Carolina Railroad.

In the new government required under the congressional plan of Reconstruction, Caldwell was elected lieutenant governor on the Republican ticket headed by William W. Holden. As the presiding officer of the senate, he served with considerable tact and fairness to all factions. On 20 Dec. 1870 he assumed the duties of governor, when Holden was suspended from office pending his impeachment trial before the senate. Upon Holden's removal on 22 Mar. 1871, Caldwell became governor.

As governor, he faced the difficult task of working with a General Assembly dominated by Conservatives hostile to the very existence of the Republican party in the state. Nevertheless, his sense of moderation and an obvious integrity in the performance of his duties went far not only to appease many of his political foes but also to win support for his much-abused party. Although his staff was reduced by the General Assembly to one secretary and his authority under the constitution challenged, he vigorously sought solutions to the more vexatious problems confronting the state during Reconstruction. He especially pressed the legislature for a systematic settlement of the state debt, which he claimed amounted to thirty-eight million dollars in 1873. He proposed that a compromise "be effected with the creditors, by which the whole debt could be reduced to an amount within the capacity of the State to pay." The General Assembly refused to cooperate with the scalawag governor in any plan for the settlement of the debt. When an arrangement with the state creditors was finally made in 1879, it followed Caldwell's general recommendations, although the conservative regime probably reduced the total amount of the debt far more than he would have desired.

With little success, Caldwell repeatedly urged the General Assembly to reinvigorate the languishing public school system that the Republicans had begun with considerable promise in 1868–69. He demonstrated no similar interest in the state university, which he believed "may be dispensed with until a new era of prosperity shall dawn upon us." As chairman of the board of trustees, he cautiously but unsuccessfully worked to place the university in the hands of "reliable Republicans" in anticipation of its reopening, after the closure of 1870.

He also futilely sought legislative action to restore law and order in the state and provide protection for the rights of Black citizens, as called for by the Fourteenth and Fifteenth amendments. Caldwell's vigorous effort to prosecute the notorious Milton S. Littlefield and George W. Swepson, although ending in failure, demonstrated his determination to act scrupulously in enforcing the laws of the state against violators, despite possible close ties between the corruptionists and members of his party.

As a result of his successes, and in spite of the attempts of the Conservatives to discredit him, Caldwell in 1872 defeated Augustus S. Merrimon for governor by a margin of 1,898 votes. He did not live out the new term; he died suddenly at Hillsborough.

Caldwell was married in 1840 to Minerva Ruffin Cain of Hillsborough; he was the father of three daughters and two sons.