10 June 1820–30 Dec. 1909

See also: William Preston Bynum, II, nephew.

William Preston Bynum, jurist, prosecutor, and lawyer, was born on the plantation of his father, Hampton Bynum, on Town Fork one mile south of Germanton, in Stokes County. Bynum's grandfather was Gray Bynum, a native of England who moved south of Germanton from Virginia, with his friends Anthony Hampton and Joseph Winston, in about 1760; all three built homes within sight of one another on Town Fork. Gray Bynum married Margaret Hampton, daughter of Anthony and Ann Preston Hampton, and from this union came William P. Bynum's father, Hampton. In 1772, Anthony Hampton sold his land at Germanton to Gray Bynum and moved to Spartanburg, S.C., to establish there the Hampton family that included three Wade Hamptons, the last of Civil War fame. Hampton Bynum married Mary Coleman Martin, daughter of John and Nancy Shipp Martin, and they reared five boys and three girls: William Preston, John Gray, Wade Hampton, James, Benjamin Franklin, Margaret, Harriet, and Martha. William received a log-school education near Germanton before he entered Davidson College in 1837. Being graduated as valedictorian of his class on 4 Aug. 1842, Bynum next read law under Richmond M. Pearson and was admitted to the bar in Rutherfordton.

After practicing law in Rutherfordton, Bynum moved to Lincoln County, where he married Ann Eliza Shipp, a cousin, on 2 Dec. 1846. Ann Eliza was the granddaughter of Thomas Shipp (Bynum's great-grandfather), the daughter of Bartlett Shipp, and the sister of Judge William M. Shipp of the North Carolina Supreme Court. Bynum practiced law at Lincolnton until the Civil War erupted.

Although he came from a Federalist-Whig family of strong nationalist convictions and although he opposed secession, Bynum was elected a lieutenant of the Beatties Ford Rifles and later was commissioned lieutenant colonel of the Second North Carolina Regiment, effective 8 May 1861. Bynum saw military action with the Second Regiment at the Seven Days' Battle, Mechanicsville, Cold Harbor, Malvern Hill, and Sharpsburg, and the regiment was in reserve at Fredericksburg. When the First Regiment lost all regimental officers at Malvern Hill, Bynum temporarily commanded it. When the Second's commander, Colonel Charles Courtenay Tew, was killed at Sharpsburg, Bynum commanded the Second. Bynum's military career ended on 21 Mar. 1863, when he resigned after the legislature elected him solicitor of the Seventh Judicial District on 2 Dec. 1862.

Bynum's political career spanned the years 1863 to 1879. It required great physical and moral courage to prosecute the numerous and violent lawbreakers in the mountain counties from 1863 to 1873, but Bynum had these qualities in abundance. His statement during Reconstruction that he needed no help from federal authorities to enforce the law won public acclaim. In 1865 he was elected a delegate from Lincoln County to the North Carolina Constitutional Convention. He helped to draft important amendments to the North Carolina Constitution, some of which the voters rejected. In 1866 he was elected to one term in the state senate to represent Lincoln, Gaston, and Catawba counties. In 1868 both political parties nominated him for a second term as solicitor, and he was elected. In the election of 1868 he threw his support to General U. S. Grant and the Republican party.

On 20 Nov. 1873, Bynum resigned his solicitorship to accept appointment from Governor Tod R. Caldwell to the unexpired term of Associate Justice Nathaniel Boyden of the North Carolina Supreme Court. Although Bynum had changed his political affiliation to Republican before his appointment to the supreme court, the epithet "scalawag," in its demeaning sense, could not be applied to him. His peers ranked him in company with Ruffin, Henderson, and Pearson as one of the ablest jurists to sit on the North Carolina bench. Before his term expired on 6 Jan. 1879, Bynum wrote some 346 opinions, including dissents, which revealed his great common sense, native reasoning ability, and clarity of style. His dissent in State v. Richmond and Danville Railroad Company warned that corporations might undermine government by the people. In Manning v. Manning he refused to interpret the law as granting wives greater property rights if the broader interpretation would undermine the institution of marriage. But in Taylor v. Taylor, he declared his loathing of the custom of wifebeating. In Lewis v. Commissioners of Wake County, Bynum expressed a willingness for grand juries to investigate broadly but not to the point of becoming inquisitory; his dissent in Wittkowsky v. Wasson, however, revealed his commitment to the broad jurisdiction of the trial jury as being the best guardian of the rights of a free people. State v. Blalock was a landmark decision, broadening the definition of justifiable homicide. Bynum's decisions give evidence that he was greatly concerned that the letter and the spirit of the laws be observed.

In 1878 the Republican party urged Bynum to run for another term on the supreme court, but he refused that and all future entreaties to return to politics. In 1879 he took up residence in Charlotte, where he remained and pursued his legal career until his death.

There were born to Bynum and his wife two children, Mary Preston (1849–75) and William Shipp (1848–98), a lawyer and Episcopal clergyman of Lincolnton. By William Shipp and his wife, Mary Louisa Curtis, daughter of Moses Ashley Curtis, Bynum had eight grandchildren. Bynum's wife died in June 1885. One granddaughter, Minna, married Archibald Henderson, a noted mathematics professor of The University of North Carolina.

Having achieved financial independence by 1879, Bynum was able to engage in philanthropy. On the death of his grandson, William Preston, at The University of North Carolina in 1891, Bynum built a gymnasium in his memory. He also constructed Episcopal chapels at the Thompson Episcopal Orphanage and in Greensboro.

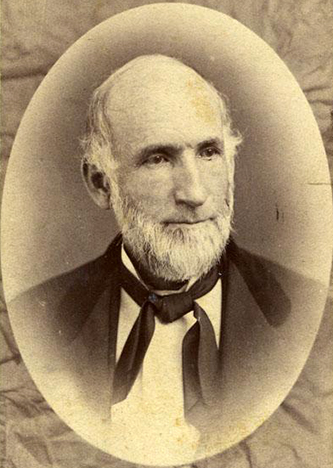

There is a portrait of Bynum in the North Carolina Supreme Court Building.