8 May 1751–6 May 1839

William Lenoir was a Revolutionary War officer, justice of the peace, state legislator, and planter-entrepreneur. He was born in Brunswick County, VA, and was the youngest of ten children of Thomas and Mourning Crawley Lenoir. William was eight when his father sold his Virginia plantation and moved the family to richer farmland in Edgecombe County, N.C. Before William received the education he desired his father died in 1765, leaving the fourteen-year-old to manage family affairs. Lenoir spent his leisure studying mathematics, enabling him in 1769 to open an elementary school in Brunswick County and in 1770 to establish a similar school in Halifax County.

In 1771 he married Ann Ballard of Halifax County and the following year their first child, Mary, was born. No longer able to support his family on the income of a teacher, Lenoir chose the more lucrative profession of surveying. In 1775, after mastering the new trade and deciding to seek opportunities in sparsely settled western North Carolina, he moved his small family to that part of Surry County that became Wilkes County in 1778.

Lenoir had barely established his new farm when the Revolutionary War erupted and he joined the Patriot cause by enrolling in the local militia. In 1776, he received command of a ranger company that patrolled the Blue Ridge Mountains. The company served to protect the establishments of white settlements on American Indian lands. He also led troops in Rutherford's Campaign of 1776 and four years later in the Battle of Kings Mountain, when he was wounded twice. In Pyle's Massacre of 1781 near the Haw River, Lenoir's horse was shot from under him and his sword was broken, but he escaped injury when the Patriot force overwhelmed an outnumbered Loyalist band. Sources cite that Lenoir had an aptitude for assembling supplies and arms as well as recruiting soldiers throughout the war.

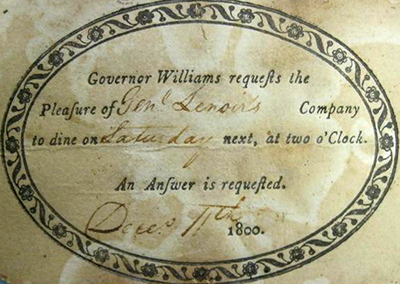

Lenoir's affiliation with the state militia did not end with the Revolution. He encouraged regular musters to keep units of the Fifth North Carolina Division in readiness. This was especially true during the early 1790s, when war between England and France threatened to involve America. Although Lenoir resigned from the military establishment in 1794 after being passed over for a division command in a statewide militia reorganization, he accepted in 1795 the commission of major general to take charge of the Fifth Division. He sought to strengthen the citizen army by pleading with state government officials for supplemental arms for his troops and for passage of stricter military regulations, and by encouraging better preparedness and self-discipline among his subordinates. In 1812, he mobilized over a thousand men to serve in the War of 1812, but his long military career ended with his resignation after he refused to serve under a despised political opponent.

Lenoir's leadership during the Revolution gained him the necessary local support for an appointment in 1776 as a Wilkes County justice of the peace and in 1778 as the county's clerk of court. Fellow justices and other county residents elected him to the North Carolina House of Commons in 1781. Lenoir served three terms in the house, won election to the state senate for the years 1784–85 and 1787–95, and was speaker of the senate during his last five terms. A delegate to the state ratifying conventions of 1788 and 1789, he voted against the U.S. Constitution because it did not contain a bill of rights. In 1789 he was designated a trustee of the newly chartered University of North Carolina and acted as president pro-tem at the first meeting in 1790.

William Lenoir lost his senate seat in 1795 to James Wellborn, whose campaign criticizing Lenoir's activities in land speculation took Lenoir by surprise. Believing a candidate should "stand for office" rather than electioneer for it, Lenoir ensured his defeat by not presenting his own political views to the electorate. He stubbornly maintained this view later in unsuccessful races for the U.S. Senate (1789), North Carolina governorship (1792 and 1805), North Carolina Senate (1802), and U.S. House of Representatives (1803 and 1806). He was a Jeffersonian Republican and a Whig.

While continuing to serve as justice of the peace, Lenoir enjoyed considerable prosperity as a planter-entrepreneur. In addition to making money from the sale of crops grown on his plantation, Fort Defiance, he supplemented his income by operating a blacksmith shop, breeding horses, and lending money; he received revenue from idle acreage by leasing land to farmers whom he required to practice land conservation. Lenoir was successful in buying and selling his holdings of over 10,000 acres. But as a member of Rousseau and Company, he encountered difficulty during 1795–96 in managing the sale of over 100,000 acres of local land to Pennsylvania agents and received only a meager profit for the effort.

The wealth and labor of Lenoir's personal estate was supplemented and maintained by enslaved laborers. At the 1790 census, Lenoir was listed as the enslaver of twelve people. The amount of people Lenoir enslaved increased throughout his life. The 1820 census lists Lenoir as the enslaver of forty-one people. Lenoir also frequently purchased enslaved children to work at Fort Defiance due to their lower cost and aptitude for training. Lenoir viewed the institution of slavery as morally just, and stated that it existed for the protection of the slaves from the harmful uncertainties of freedom.

If Lenoir's land company endeavor was a financial fiasco and provided a political issue to help defeat him, his own acquisition of Moravian land in Wilkes County during the Revolutionary War was even more costly. Following the confiscation acts of 1777 and 1799 authorizing the expropriation of Loyalist property in North Carolina, he and county citizens claimed property held in trust for the Moravians of Forsyth (then Surry) County by a British citizen, Henry Cossart. In 1793 the Moravians entered a suit of ejectment against the Wilkes claimants, and the ensuing cases of Marshall v. Loveless and Others and Benzien and Others v. Lenoir and Others dragged through superior and state supreme courts for over thirty years. The tribunals ruled against the defendants, contending that Cossart's trust was valid and that as North Carolina citizens the Moravians were not subject to confiscation acts. As a result, Lenoir lost several thousand acres of land, over a thousand dollars in back rent, and a legal struggle that he considered to be a moral issue.

Lenoir had nine children: Mary, William Ballard, Ann, Thomas, Elizabeth, Walter Raleigh, Eliza Mira, Martha, and Sarah Joyce. His wife's name was Ann, and the two lived together for sixty-three years until her death in 1833. Lenoir died six years later.

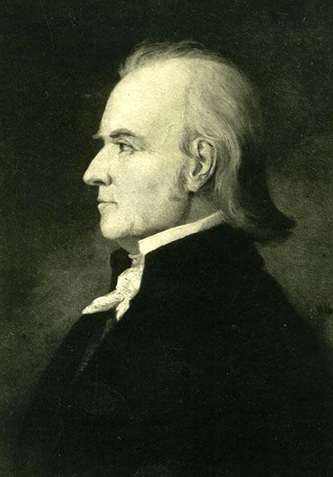

Lenoir was buried in the family cemetery at Fort Defiance. Lenoir is recognized in the naming of Lenoir County, a town in Caldwell County, a street in Raleigh, and a building at The University of North Carolina for him. His portrait hangs in South Building on the Chapel Hill campus. He was a Freemason.