See also: Bath; Ports and Harbors

Introduction

Port Bath operated from 1716 to the 1790s as one of five regional British-American customs collections districts (including Port Currituck, Port Roanoke, Port Bath, Port Beaufort, and Port Brunswick/Cape Fear) along the coast of North Carolina in the eighteenth century. Today visitors can experience the state's first town and Bath's 300-year history among its surviving colonial structures and at Historic Bath. The home of Port Bath’s longest serving 18th century Collector of Customs, Colonel Robert Palmer, loyal aide de camp to Governor Tryon, still stands. Located on the old Water Street in Bath, the 1751 Georgian home with massive twin chimneys is open to the public today. The home was once occupied by three important early merchant families who traded in Port Bath and beyond: the Coutanches, the Palmers, and the Marshes. Historic preservation efforts in Bath have saved St. Thomas Church, the Palmer-Marsh House (a National Historic Landmark), Van Der Veer House (ca. 1790), and the Bonner House (ca. 1830). The town historic district, encompassing the original town limits, has been listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

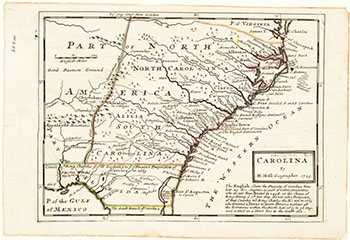

Origins of Beaufort County and the Town of Bath, North Carolina's first incorporated town

In the first decades following the 1663 Carolina Province Charter issued by King Charles II, shipping and commerce depended initially on Roanoke and Currituck Inlets serving Albemarle County , the now extinct county below Virginia. The two northeast inlets were slowly closing or shoaling up, and monitoring shipping increasingly became more complicated as vessel traffic to the growing interior was re-routed through Ocracoke Inlet. Furthermore, due to over-supply and quality considerations, a Virginian embargo had prohibited North Carolina tobacco importation by land or by sea. A transatlantic port from which to inspect and ship tobacco, commodities, and other exports to other colonies and England was a vital necessity for the prosperity of North Carolina, which would otherwise be entirely at the mercy of New England shippers.

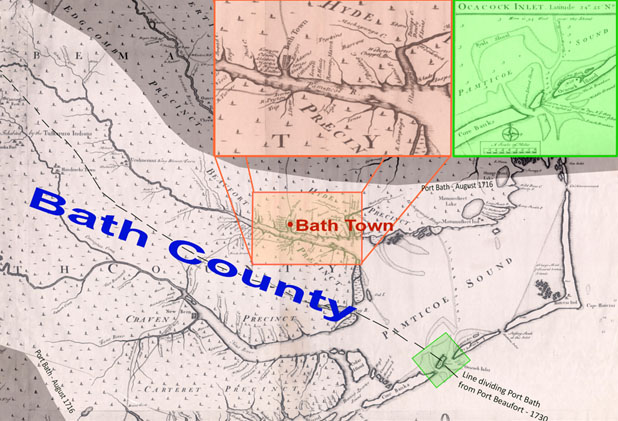

Bath County became North Carolina’s second county in 1696. Its first village was the fur trading peninsular settlement of Pamtico, also spelled Pamtecough: the village was named after the Algonquin Pomouik tribe village near Old Town/Bath Creek. Pamtico was renamed as Bath Town, chartered March 8, 1705 as the county seat and the state’s first town. Bath County, also now extinct, was originally composed of three precincts Pamplicough, Wyckham and Archdale, each precinct divided into parishes. The precincts were renamed in 1712, changing to Beaufort, Hyde, and Craven. Beaufort Precinct was to eventually become today’s Beaufort County and Pitt County.

Origins of Port Bath: North Carolina's first official port of entry

In the early 18th century colony administrators and the Lords Proprietors recognized Beaufort Precinct in Bath County and its town of Bath as the best

opportunity for an official British-American port of entry to handle provincial navigation and trade required duties. North Carolina petitioned the Lords Proprietors through Governor Charles Eden in 1715 and they approved and decreed Port Bath on August 1, 1716, the first official port of entry. As the population and towns in North Carolina and the twelve other original colonies grew, by 1770 the number of total British ports of entry in North America increased to sixty. States with less lengthy coastline on the Atlantic Ocean like New York and Rhode Island had only one port district, compared to North Carolina with five official ports of entry and Virginia and Maryland with even more.

The British-American colonial ports were administered by regional governor-appointed port officials and London-commissioned British Navy officers. All customs house officials, collectors, comptrollers, and district naval officers, submitted periodic shipping lists to the London Customs House in the mother country summarizing shipping activity, vessels, cargo, crew, guns, and duties collected. Port duties were based on British Navigation Acts, maritime trade regulations issued by British Parliament, Board of Trade instructions, as well as legislation by local town, county, and provincial North Carolina government.

Obstacles to enforcement of regulations and growth

A major obstacle for Port Bath was enforcing regulation over such a large area. The old County of Bath extended from the Outer Banks up to the Piedmont area in the early 1700s. Port Bath district covered a similar area; composed of both the Pamlico and Neuse River basins, with Atlantic entry through Ocracoke Inlet. It covered a broad crescent shape from Ocracoke, through Bath and New Bern up to modern Wake, Orange and Caswell Counties. In 1723 Bath County’s first naval officer, John Dunston, was assigned an even larger district - “everything north and east of Cape Fear,” as part of the mother country’s trade checks and balances scheme to monitor her growing colonial empire.

Another factor inhibiting Bath County’s early economic growth and its port district involved the absence of roads in the Carolina back country. Europeans had only recently arrived in the Bath wilderness. Many were transplanted Virginia settlers who joined farmers and met Native Americans, bears, panthers, bison and other wildlife found there in the undeveloped Indian country as described by John Lawson in his 1709 A New Voyage to Carolina. Col. Robert Quary, the “Surveyor General of Customs for North America and the Adjacent Islands,” recognized Bath County’s maritime promise and established a store trading post just outside Bath. His plantation and store was located “between Back Creek and Romney Marsh” on the Pamlico River as early as 1700. Based in Philadelphia and responsible for collections over other colonies, former South Carolina Governor Quary, an ardent Anglican, had influential trading partners in London, Virginia, South Carolina, and Pennsylvania. Together they and many other English, Scottish and Irish merchants in the course of the 18th century opened the door to greater business opportunities for Bath County and the northern half of Carolina.

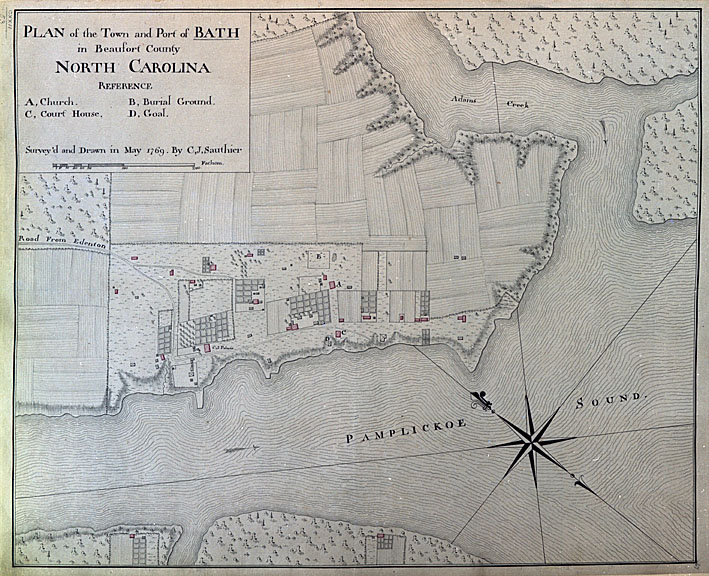

Customs collectors clearing vessels and cargo, whether with or without a customs house base of operations in their district, typically covered a huge area. When Port Bath first formed, high-volume shippers, sea captains, wealthy plantation owners and other merchants benefitted greatly. A clear account of shipping could be maintained and the quality of cargoes inspected and insured. Port Bath located in the county seat offered town amenities such as town clerk office and courthouse with witnesses for filing legal documents, insurance bonds, recording wills, bills of sale and promissory notes before a voyage. The seaport town also offered port tradesmen’s services, shipwrights, blacksmiths, coopers, rope chandlers, shoemakers, carpenter/joiners, even a silversmith, taverns and ordinaries/inns, plus even a house of ill-repute.

Because the 1715 Port Bath district included two waterways, Pamlico and Neuse River basins, with tributaries leading to the interior, smaller, local vessel traffic could operate in relative secrecy. There existed countless hidden waterways, creeks, and plantation landings near settlements and trading posts for colonists to unload shallow-draft sloops, schooners, and brigs quickly and even illegally. In 1730 the Neuse River waterways and its secondary collection center in New Bern were re-assigned to Port Beaufort, halving the district but freeing Port Bath officials to concentrate on the Tar-Pamlico River basin and to expand trade upstream from the Coastal Plains into the Piedmont area. Of equal importance, inter-colonial coastal trade expanded from Port Bath to the main colonial commercial centers Philadelphia, New York, Baltimore, Boston and Charleston, even direct to London, Liverpool, Glasgow, and Bordeaux.

The early lucrative Indian fur and skin trade of the proprietary days was replaced in the royal Crown colony years after 1729 by commodity provisions, lumber and naval stores, imports of luxury goods and manufactures, as well as re-exports of West Indian trade in rum, sugar, salt and molasses.

Vice-Admiralty Courts at Port Bath

Vice Admiralty cases concerned maritime commerce in the province and infringements of Navigation Acts. North Carolina’s Vice-Admiralty court was not as visible as the provincial Common law courts but they both were used routinely by Port Bath with respect to maritime and trade law violations. Both courts were similar to those in other colonies. Only sixty Vice-Admiralty court cases are known from 1729-1750. Unusual piracy cases were tried in the Virginia and South Carolina admiralty courts, violations involving royal interests were automatically referred to London Admiralty Court.

As early as 1704, a Bath County sloop, the Pamlico Adventure was seized at Pamlico by deputy collector Barrow for “breaking bulk before entry,” i.e. unlawfully unloading. Domestic cases fell into four groups: Navigation Acts violations, prize causes (seized proceeds), recovery of past condemnation moneys, and ordinary mercantile cases such as seamen’s wages, shipwrecks and salvage, pilot fees, and vessel appraisals.

Late 19th century and early statehood: the diminishing role of Port Bath

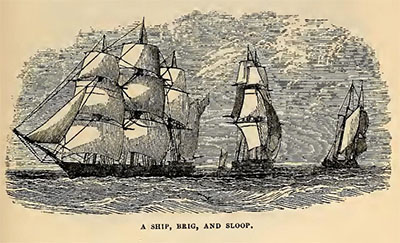

Late 17th and 18th century creeks and waterways in the Port Bath district would have been full of rafts, skiffs, periaugers, shallops, small fast Bermuda-rigged sloops, shoal-draft Chesapeake-rigged two-masted schooners and planter-merchant brigs. In the very early 18th century only wealthy London merchants owned or chartered larger three-masted merchant ships that sometimes were offloaded onto smaller vessels (lighters) at the Ocracoke bar. As the American shipbuilding industry grew, more Carolinians bought or built vessels alone or with partners. Port Bath officials every month cleared inter-colonial and oceanic vessels carrying naval stores, rum, merchandise and manufactured items, lumber, staves for barrels and kegs, commodities, provisions, passengers, and mail.

After its first decades of growth, Port Bath’s shipping activity diminished but remained steady at least a decade after the American Revolution. Port Bath’s shipping activity in surviving 1761-1790 records shows predominant use of sloops and schooners size range averaging 30-50 tons, and occasional clearances of larger brigs and ships of 75-200 tons. The maximum size sailing vessel recorded clearing Port Bath was a merchant ship of 250 tons. Surviving shipping lists show a wide variety of imports: rum, sugar, merchandise, and molasses came in to Port Bath from the West Indies, which were then traded for other goods or re-exported to other colonies. Salt came from the Turks and Caicos, linen from Ireland, wine from Madeira and Bordeaux.

Port Bath shipped out shingles, naval stores, staves for barrels, lumber, rum, tobacco, skins and commodities like pork, corn, and beans. Unlike Charleston and the Cape Fear region, Port Bath planter-merchants generally did not import slaves or export large quantities of rice or indigo.

Port Bath ultimately played a pivotal role in the early 1700’s particularly during North Carolina’s expansion of maritime commerce buying time and enforcing regulations while other deep water ports and/or new towns like Charleston, Baltimore, Beaufort, New Bern, Brunswick and Wilmington were growing. Scattered shipping records of Port Bath clearances have survived in North Carolina, the old colonial ports, London, and foreign ports, all acknowledging the importance of North Carolina’s first official port of entry.

As roads developed to the interior linking Halifax, New Bern, and Wilmington, Bath eventually was bypassed by vessels choosing to load and unload goods a few miles upstream at the settlement called Forks of the Tar, later renamed Washington in 1776 and incorporated 1782. In 1784, November 19, Nathan Keais, John Gray Blount and Richard Blackledge, Commissioners at the time petitioned the Assembly to transfer the seat of county government from Bath, the oldest incorporated town in the state, to Washington. A new courthouse was built in 1787, the second oldest federal courthouse today in North Carolina. The last known Customs Collector of Port Bath, Capt. Nathan Keias moved from Bath to Washington and bought a lot in the new town next to John Gray Blount. Captain Keias and John Gray Blount are buried near one another in the St. Peter’s Episcopal Church cemetery in Washington.

Sometime in the early 1790’s Port Bath Customs Collection District vanished, replaced by the new Continental Customs and Impost District of Washington. In 1796 records indicate 130 vessels were entered in the Washington Customs House reports. On September 2, 1805, the Raleigh Register reported that “In less than 17 years from its first establishment as a town, the port of Washington owned more tons of shipping than any other port in the state.” And in 1812, a Customs House was built in Washington for the new Continental Customs District.