At the turn of the twentieth century, the Democratic government in Raleigh launched a series of educational initiatives to improve public schools in the state. Appalled by the number of children younger than 14 employed in cotton mills, Governor Charles B. Aycock emphasized the importance of education for all North Carolinians in his inaugural address of January 1901 (Aycock's actual policies reflected his desire for a better-educated white population to keep the Democrats in power). The new governor soon formed the Central Campaign Committee for the Promotion of Public Education, which began operations in 1902 from its headquarters in the office of Superintendent of Public Instruction James Y. Joyner. The committee's stated purpose was to advance public education through all possible legal means, such as campaigning for local school taxes, consolidation of school districts, better school buildings and equipment, longer school terms, and better-trained and higher-paid teachers.

Also in 1901, the General Assembly under Aycock's leadership directly appropriated tax funds for public schools for the first time in the state's history. Legislation in 1905 provided that every county school board require all children between ages 8 and 16 to attend school for a 16-week term annually. The Rural High School Act (1907) and consolidation of rural school districts, as well as a program of "equalization" in the distribution of funds for education, led to the gradual improvement of free public education. By 1911, 200 public rural high schools were distributed among the state's 100 counties.

In 1907 Asheville city schools became the first school system in North Carolina to finance public kindergarten, but decades passed before kindergarten became a permanent grade in public schools statewide. The General Assembly of 1913 enacted the first statewide law compelling school attendance. The Compulsory Attendance Act required that all children, both Black and white, between the ages of 8 and 12 attend school continuously for four months a year, allowing reasonable exemptions and providing reasonable penalties and adequate but inexpensive machinery for its enforcement. Increasingly, the state's child labor laws supported compulsory school attendance by raising the minimum age at which a child could begin to work.

The legislature began to fund public elementary schools for African Americans in 1910 and established the Division of Negro Education in 1921 to oversee the education of Black children in many rural schools. High schools for Black people became available only after 1918, when the state's first Black secondary school was built. Except in the more progressive (and urbanized) counties of Durham, Forsyth, Guilford, Mecklenburg, and Wake, secondary education for Black people progressed slowly.

In reality, and despite occasional legislative initiatives and the continued efforts of various Black advocacy groups and philanthropic organizations, the public education of the state's Black children under Jim Crow remained strikingly inferior to that of white children. The separate-but-equal doctrine adopted by the state in 1875 and subsequent Jim Crow statutes passed in the early 1900s solidified the second-class status of publicly supported Black schools. For example, the 1903 law clarifying that no North Carolina child with "Negro blood in its veins, however remote the strain, shall attend a school for the white race, and no such child shall be considered a white child" displays this difference in educational priority.

As civil rights advocate and author Pauli Murray describes in her autobiography, Proud Shoes: The Story of an American Family (1956), the North Carolina educational system during the early decades of the twentieth century was focused almost exclusively on the progress of whites, with little regard for the success of Black people. Growing up in Durham in a multiracial family, Murray experienced not only the pain of segregation and the squalor of Black facilities but also the pride and determination of many Black teachers and students. Murray poignantly remembers the "beautiful red-and-white brick building" that served as the whites' school, in contrast to the rundown wooden building with "bare and splintery" floors for Black students. Such inequities would not be addressed by political leaders in North Carolina for decades, and then only after federal intervention.

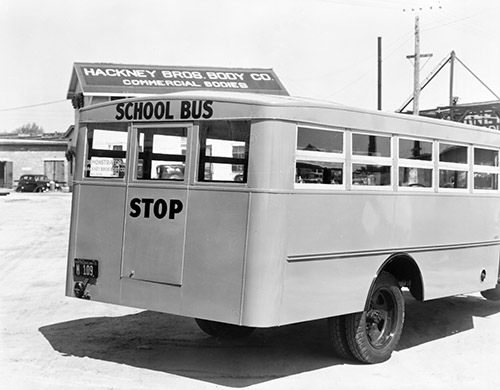

Busing of students to and from public schools was initially authorized by the General Assembly in 1911. Craven County schools were the first to transport schoolchildren under this new measure, and in 1917 Pamlico County became the first to purchase a "school truck" for that purpose. By 1928 every county in the state provided pupil transportation, albeit limited in some areas.

After World War I, the strategy of school consolidation-with the goal of improving the quality of the state's rural public schools-began to gain momentum in the North Carolina legislature and among local school boards. The one- and two-teacher schools serving rural districts were incapable of competing economically with the larger facilities of towns and cities, and rural children were suffering the consequences. Consolidating several small districts into one pooled available resources and afforded less-populated areas the advantages of better-funded urban schools. The initiative saw many positive results, as school curricula expanded to include several new subjects and vocational opportunities, and many rural districts began offering high school courses for the first time. An ever-increasing number of students would come to be served more effectively by new facilities born of the consolidation movement.

Severe economic conditions during the Great Depression greatly slowed the progress of public education in the state and nation. To eliminate some of these hardships in North Carolina counties, which were primarily responsible for funding local schools, the 1931 and 1933 sessions of the General Assembly enacted the School Machinery Act. This statute essentially transferred financial support and control of public schools from the counties to the state, established a new sales tax as the source of funding, and designated counties as the "basic governmental unit" responsible for building and maintaining public school facilities and providing additional funds for specific programs and improvements. At this time, the state assumed the cost of textbooks, school supplies, and other necessities.

Throughout the 1940s, North Carolina's public school system continued to grow and change. In 1942 a twelfth grade was added to high school. The following year saw the introduction of school lunches and the lengthening of the school term to nine months. In 1946 the compulsory attendance age increased from 14 to 16. Voters in 1949 approved a $50 million state bond for construction of public schools, the first of its kind in the state. The State Textbook Commission, originating in the early twentieth-century initiatives of Aycock and other progressives, in 1945 gained jurisdiction over the selection and use of textbooks at both the elementary and secondary levels.