Related Entries: Cherokee People in North Carolina; Asheville; Regions; Important Revolutionary War Sites: Quaker Meadows, N.C.; Watauga Settlement

With some of the oldest and most complex geographical formations on earth, the Mountain Region of western North Carolina has many of the highest summits in eastern America. In fact, Yancey County's Mount Mitchell, in the Black Mountain range, is the highest point east of the Mississippi River. The Mountain Region consists of many mountain ranges, including the Blue Ridge, Black, Great Smoky, Balsam, and Nantahala Mountains. This beautiful land of peaks and valleys and forests and flowers was the last area of North Carolina to be settled by European Americans.

White Settlement

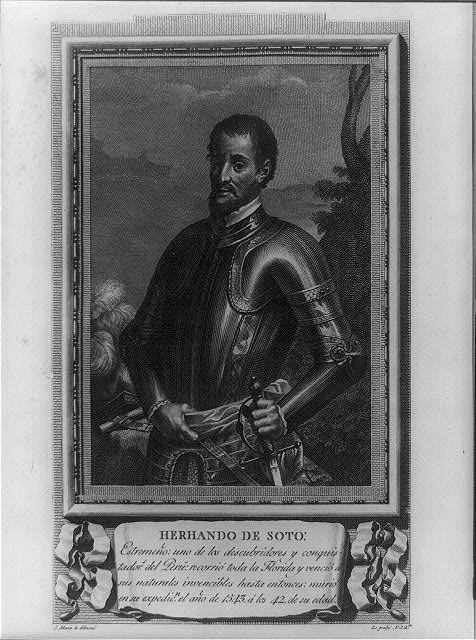

The most prominent American Indian tribe to live in the mountains of western present-day North Carolina were the Cherokee. Their first known contact with Europeans occurred in 1540, when Spanish explorer Hernando de Soto and his men came to the mountains in search of gold. Following this brief encounter, the Cherokee and Europeans had limited contact until the late 1600s. A thriving trade developed between the Cherokee and white settlers in the early 1700s. Goods such as animal furs became popular. To maximize profits, white traders began to monopolize the trade. This created tension between existing Cherokee fur traders and the settlers.

Much of western North Carolina served as hunting and foraging grounds for other American Indian tribes, like the Catawba and Nottoway peoples. Some tribes also agreed via treaty that the land would have no permanent settlements and would be used for each to hunt freely. White settlements began and continued to appear on this land, which further complicated relations with American Indian people. These tensions pushed the British government to issue the Proclamation of 1763. It limited white colonization of American Indian lands.

White settlers passed through the northwestern mountains and became permanent residents of the Watauga settlements (now in Tennessee) in the 1770s. These settlements ignored the Proclamation. During the Revolution, white militias from North Carolina, South Carolina, and Virginia burned and removed Cherokee towns from the area, like Nikwasi. The military campaign became known as Rutherford’s Trace. But some of the earliest permanent white settlers in the North Carolina Mountain Region came to the Swannanoa area of what is now Buncombe County about 1784. Among these early settlers were the Davidsons, Alexanders, Gudgers, and Pattons.

Many Cherokee diplomats fought against white settlements. Old Tassel and Dragging Canoe were two that were outspoken. In southwest North Carolina, violent raids and attacks to resist white settlement occurred. Conflicts lasted for many years all along the Appalachians. White settlers continued to immigrate into the area just west of the Blue Ridge Mountains in the late 1700s. As a result, white migration into present-day Buncombe, Henderson, and Transylvania Counties grew rapidly for a while. White settlers continued to immigrate into the area just west of the Blue Ridge Mountains in the late 1700s. As a result, White migration into present-day Buncombe, Henderson, and Transylvania Counties grew rapidly for a while.

White colonization of Cherokee land also increased after the State of Franklin formed. On August 23, 1784, eight counties in western North Carolina (now Tennessee) seceded their lands from the state and remained seceded until 1788. Franklin’s Declaration of Independence and the December 1784 Constitution both outlined protection for white settlers against American Indian “raviges [sic].” The Franklin state militia, and its leader John Sevier, attacked American Indian people within its borders to cement white settlement of the region.

The new settlers in the Mountains found it difficult to travel the steep, rough, and muddy roads back and forth to their county seats in Rutherford, Burke, and Wilkes Counties. They had to go to these county seats to pay taxes, buy or sell land, go to court, or carry on other business. The settlers began to ask the legislature to establish new counties so they would not have to travel so far to county seats. In response, the legislature established Buncombe and Ashe Counties in 1792 and 1799 respectively. Morristown, or Moriston (present-day Asheville, was founded as the county seat of Buncombe County because it was centrally located at a major crossroad. Jefferson was named the county seat in Ashe County.

The settlers who came to the Mountains were primarily of English, Scotch-Irish, and German descent. They came to buy, settle, and farm the cheap, fertile bottomlands and hillsides in the region. Some migrated from the North Carolina Piedmont and the Coastal Plain. They came by foot, wagon, or horseback, entering the area through gaps such as Swannanoa, Hickory Nut, Gillespie, and Deep Gaps.

Other English, Scotch-Irish, and German settlers came from Virginia, Maryland, and Pennsylvania. They traveled down the Great Wagon Road to the Piedmont Region of North Carolina and then traveled west to reach the mountains.

Black Settlement of Appalachia

Enslaved black people were brought into the Mountain Region to work some of the farms. Some farms were small and some others were large. Some wealthy enslavers (those who held people in slavery) and their families like that of Nicholas W. Woodfin of Buncombe Country enslaved people throughout their life. Robert Love of Haywood County, for example, enslaved one hundred people. Zebulon Vance, future governor of North Carolina, also enslaved people in his Asheville household. Enslaved labor was prominent among wealthy whites in Appalachia and brought many Black people to the region. Enslaved laborers worked in many trades, including farming and hospitality.

The Buncombe Turnpike and Gold!

Problems with travel and trade changed with the completion of the Buncombe Turnpike in 1827. The turnpike followed the French Broad River north of Asheville to reach Greeneville, Tennessee. South of Asheville, the turnpike continued to Greenville, South Carolina. The turnpike was a better road than previous roads in the Mountain Region, which usually had been steep, narrow paths. It connected the North Carolina Mountain Region with other, larger markets.

Drovers were now able to drive surplus hogs, geese, or turkeys to markets outside the Mountain Region. Farmers could now use their wagons to transport crops to market. Tourists could now reach the mountains more easily. They could come in wagons, carriages, or stagecoaches, rather than on foot or horseback. Asheville and Warm Springs (now Hot Springs) became popular tourist destinations. Flat Rock attracted many summer residents from the Low Country of South Carolina, including Charleston.

The discovery of gold in western North Carolina brought an economic boom to the region in the 1820s and 1830s. Burke and Rutherford Counties experienced a gold rush in the mid-1820s when hundreds of miners arrived looking for gold. During this time, North Carolina became the leading gold-producing state. However, with the discovery of gold in California in the late 1840s, most of the miners left for California.

One famous immigrant who came to North Carolina during this gold rush was Christopher Bechtler Sr. He came to Rutherford County in 1830 with his son Augustus and a nephew, Christopher Jr. The Bechtlers were experienced metalworkers who had immigrated from Germany to Philadelphia shortly before coming to Rutherford County.

A short time after opening a jewelry shop in Rutherfordton, Christopher Sr. apparently realized that the regional economy was hurt by a lack of gold coins for use in trade. At the time, people in North Carolina were often using gold dust, nuggets, and jewelry as currency. Few people dared to make the long trip to the United States Mint in Philadelphia, where gold could be made into coins.

As a result, the Bechtlers decided to coin gold. They made their own dies and a press and struck $5.00, $2.50, and $1.00 gold pieces. Between 1831 and 1840, the Bechtlers coined $2,241,840.50 and processed an additional $1,384,000.00 in gold. Because of their success a branch of the United States Mint was established in Charlotte in 1837.

Development and Conflict

During the first three decades of the 1800s, economic and political conditions were poor. A steady stream of emigrating North Carolinians passed through the Mountain Region headed for points west.

North Carolina political conditions were affected by sectionalism, or conflict between the eastern and western sections of the state. At the time, each county, regardless of population, elected one representative to the state senate and two representatives to the North Carolina House of Commons. The east had more counties and, as a result, more representatives who could outvote representatives from the west.

By 1830 the western part of the state had more people, but the east continued to control the government. Calls for a constitutional convention were defeated repeatedly until 1834 when western counties threatened to revolt and secede from the state if a convention was not called.

Fortunately, a convention was called in 1835. The convention reformed the state constitution and created a more democratic government. The east would continue to control the senate, whose members were now elected from districts. These districts were created according to the amount of tax paid to the state. Because the east was wealthier and paid more taxes, it had more districts. But the west would control the population-based house because it had more people. Since neither the east nor the west could now control the entire government, the two sections were forced to cooperate. These changes benefited the western part of the state.

It was also during this period, in 1838, that the federal government forced a majority of the Cherokee people in the region to move to present-day Oklahoma. Thousands of Cherokee died during the journey that became known as the Trail of Tears. Although a remnant of the Cherokee were able to stay behind, Whites soon began to settle on the Cherokee land.

By the 1830s, transportation in the Mountains had improved and conflict between the east and west had decreased. But the Mountain Region remained relatively isolated for another fifty years until railroad lines reached the area.