If you had grown up in this area that has become North Carolina during the late 1600s and early 1700s, your life would have been very different from what it is today — forget television... forget soccer practice... forget chips and dip... forget school!

Colonial learning was largely informal

That is right — you would have had no school. Schools did not spring up in the area we now call North Carolina as they did in colonies like Maryland or Virginia. In most American colonies, people came from Europe with the intention of establishing organized, planned communities and towns.

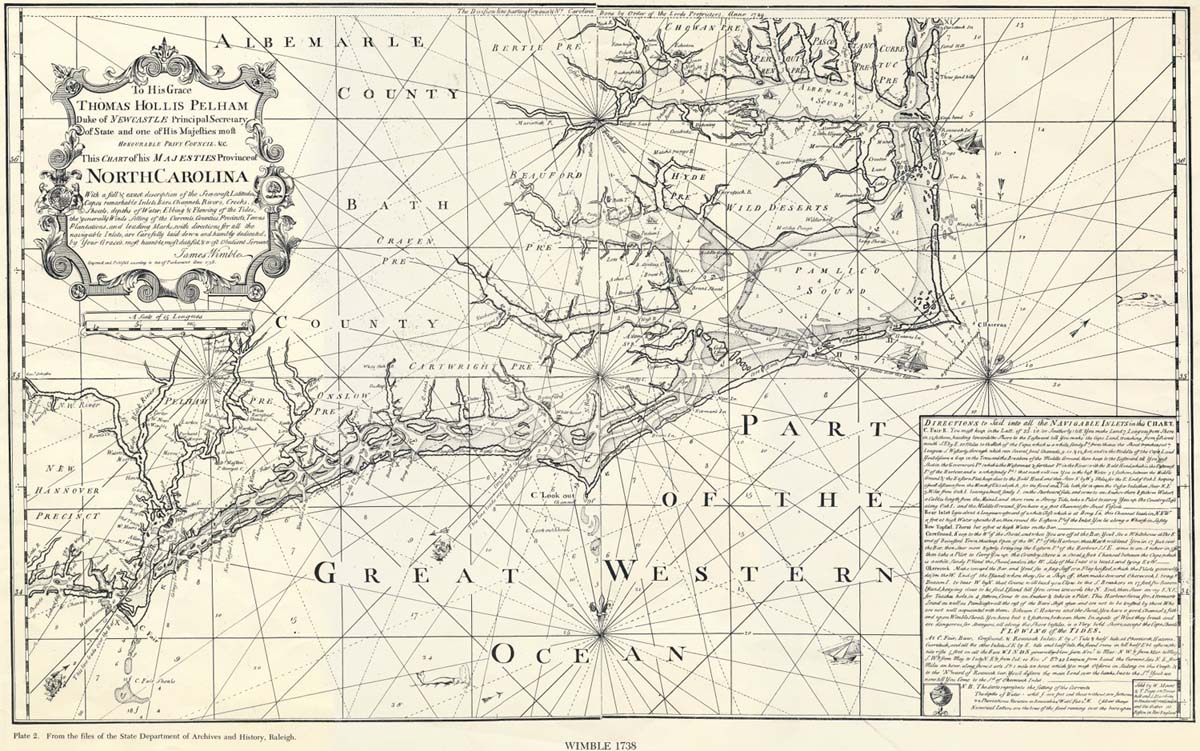

However, the settlers who drifted down into Carolina were mainly from Virginia and the northern colonies and were primarily seeking good farmland. These family farmers, who were known as yeomen, worked hard to develop small, self-sufficient farms and relied on their children to help work on those farms.

The twelve children of Augustine and Elizabeth Dishong are examples of one family who lived productive lives in colonial society. The family, which was Baptist, first owned land in Chowan County, where Augustine operated a ferry across the Chowan River. They later moved to the backcountry and operated a large, successful peach orchard in Orange County. But none of the children ever attended a school to learn to read or write.

Many children of this time received no formal schooling because their parents saw no need for the ideas taught in schools, and they could not afford to pay for it, anyway. The Dishong children, as did the majority of colonial children, learned instead by watching and imitating parents and brothers and sisters and through hearing stories told by their relatives and other elders in the community. They learned at home as time and the growing season permitted — usually after dark, between chores, or during the winter months.

Through this manner of learning, known as informal learning, the majority of the colony’s children learned what they needed to know to live in the agricultural society of this time. They learned, for example, how to plant and when to harvest crops, how to build and maintain farms, how to care for families.

Learning in the colony

The first efforts to provide formal education in Carolina were made by religious groups — the Society of Friends, whose members were also known as Quakers, the Baptists, and the Presbyterians. The Anglican Church, which was also called the Church of England, had an organization that offered schooling for young boys as one of its missions: the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts.

Even these schools, however, were not started to teach the general population. They were started to teach young boys to read, write, and speak — for a reason. Church leaders hoped that these boys would grow up to become religious leaders themselves and pass along the teachings of the holy gospel.

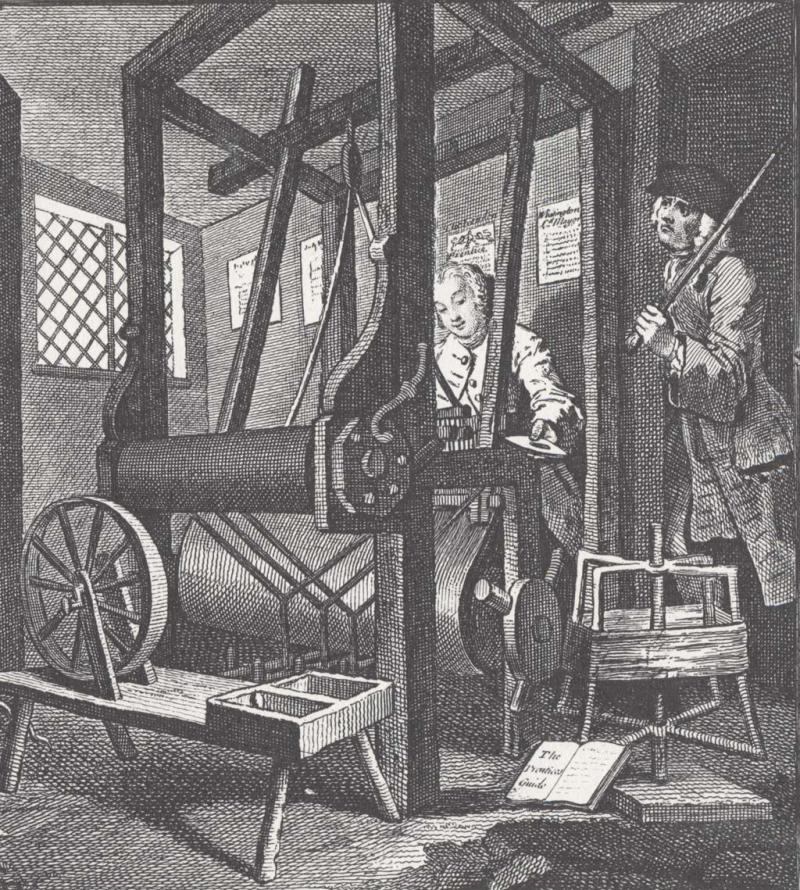

Many boys learned through apprenticeships, which had been one method of education in Europe. Some apprenticeships required that the apprentice learn skills such as math or reading or writing in order to perform his duties. Other apprentices were promised, in the contracts that bound them, some type of formal schooling as payment for their services.

Children of wealthier parents, like planters, were usually sent away to schools in other colonies or back in England. There, they learned languages like Greek and Latin, read classical literature, and studied sciences and math.

Records like old wills show the interest some of these families had in the education of their children. For example, when John Baptista Ashe died in 1734, his will instructed that his sons be taught to read and write and to learn “arithmetick” In addition, he directed, “Let them learn French” and encouraged them to prepare for a profession: one the study of law, the other, the study of “merchandize,” or business. Ashe even wanted his daughter to be able to read and write so she could learn “the management of household affairs.”

Source Citation:

Dishong Renfer, Betty. "Learning in Colonial Carolina." Tar Heel Junior Historian, Spring 1984. Republished with permission.